Hail and rain hammered the ground just inches from my boots and a frozen wind sent a shiver down my spine. My two research assistants and I were huddled together under the only shelter we could find – a glacially deposited boulder in a valley somewhere deep in the Hissar Mountain Range of Tajikistan. As I sat clutching my backpack to my body for warmth and reflecting on the challenges of the past week, I felt that maybe, just maybe, I would not succeed.

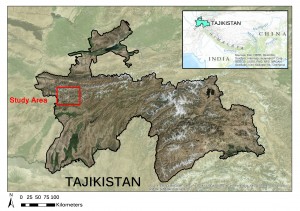

The Republic of Tajikistan is a very young country, having emerged from the former Soviet Union in 1991. Mountains, including the Pamir Range, which is often referred to as the “Roof of the World,” cover more than 90% of the country. Tajikistan is also home to a small but thriving population of the elusive cat I am now here to study: the snow leopard.

My study area, the Hissar Mountains, geographically links Uzbekistan’s Gissar Range (where snow leopards were discovered only last year) with the Pamirs in the east, meaning it may be the source of connectivity between two populations of this highly endangered species. Yet no one has ever studied snow leopards (or any wildlife) in the Hissar Range. Perhaps this is because—unlike most parts of the Pamirs—the Hissars are not protected from anthropogenic impacts such as livestock grazing, mining, or illegal hunting. They are also much more accessible to people, with parts of the range as close as 60km from Tajikistan’s capital city. This makes the Hissar Range an incredibly fascinating place to study human-wildlife interactions. Although my goals for the summer seemed easy enough at first – perform the first ever snow leopard survey in the Hissar Mountains using 40 motion-sensing cameras and DNA scat analyses, and conduct interviews to provide a local context– reality very quickly proved otherwise.

As we drove, the magnificence and ruggedness of the iron-rich peaks molded by ancient seas and glacial deposits made my jaw drop in awe. I have traveled and hiked in many amazing mountain ranges around the world, but these mountains held a unique beauty. The road quickly turned from bumpy highway to a mandatory 4WD, one-lane mountain pass, which wound along a furious river. At the end of the road, literally, a derelict guesthouse that would become our basecamp for the week greeted us.

But the elements and terrain were not in our favor. Our first day in the field, Komil, Zayniddin and I were unable to find one good site to position even one camera, and we were forced to down-climb without any protective gear in some of the sketchiest terrain I have ever encountered, and arrived back at camp two hours after dark. Immediately, I found myself questioning my physical and mental ability to do this work. The next couple days were spent waiting out intermittent rain, hail and snow storms, and because this area was as foreign to Komil and Zayniddin as it was to me, we also searched for a local guide. On day five we finally gave up on the weather and the guide, and headed back out into the rain, my assistants both without jackets and me with a stomach virus. It was on this day, after hours of hiking precipitous mountain margins and finding no sign at all of either snow leopards or ibex that the three of us took cover from a exceptionally heavy surge of rain and hail under a large boulder on the valley bottom. Each of us knew we could not continue like this – so after a short, broken conversation, we hiked back through the rain to our car and began packing to leave. Sick, soaked, struggling to communicate, and feeling like the whole project was a complete disaster, we were about to drive away when a young Tajik guy walked up to the car sporting a backwards hat and a huge grin.

Within seconds of speaking to him I knew everything would be okay. Khalil explained that he was familiar with the study area, he had contacts in several villages and valleys, and most importantly, he understood me when I articulated my goals and methods for the project. He took one look at me and told me not to worry, because he “knows every stone.” Suddenly I felt my luck changing. I had found my Tajik “Pocahontas”. Great things were coming.

Edited by Timothy Brown.