From the jungles of Ecuador to the boreal forests of Canada, local peoples around the world are fighting back against oil companies which foul the land and hoard their profits.

In some places, like the hills of Nebraska, where farmers and ranchers have so far stymied TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline, this resistance comes in the form of petitions, protests, and legal challenges. But in other countries, in which disempowerment and corruption are even more rampant than in the United States (which is really saying something), Big Oil’s opponents have been forced to register their objections through violence.

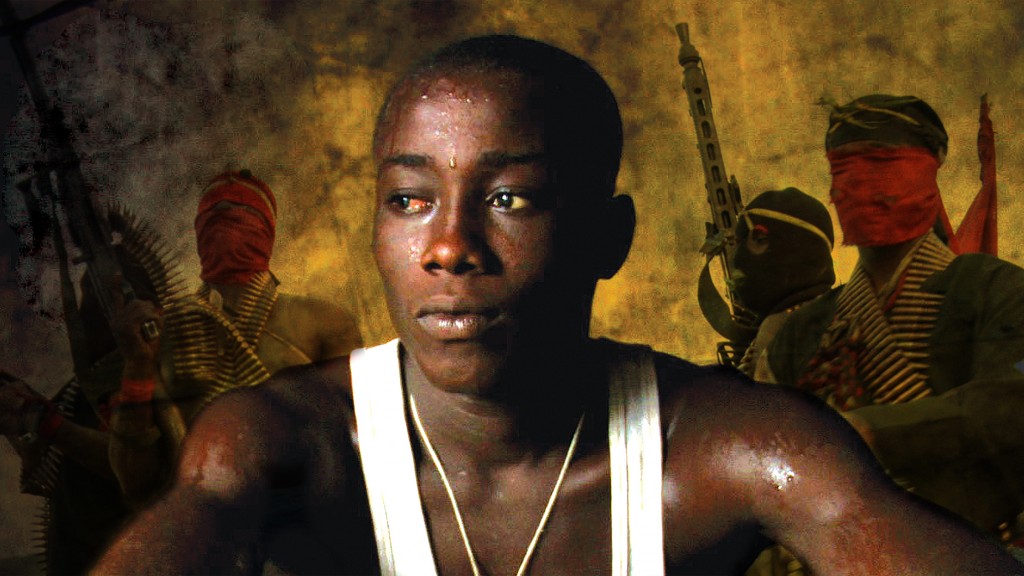

No oil conflict is more brutal and intractable than the one in the Niger Delta. For decades, foreign oil companies like Shell and Chevron have been sucking oil from the region with no regulatory oversight, shamelessly fouling the rivers and jungles upon which local people depend. In retaliation, gangs of guerilla fighters roam the delta in speedboats, waging sporadic war against the oil companies and the petro-funded military that defends the plunderers. The guerillas have met with some success: in 2008, their attacks on wells and pipelines forced Shell to evacuate oil fields and temporarily cease production. Yet the militants have also destabilized the region, incited violence against innocent villagers, and even killed the very people whose rights they claim to be defending.

In 2008, filmmaker Andrew Berends traveled to the Niger Delta to embed with the guerillas and document the conflict. Berends was no stranger to violence: one of his previous films, The Blood of My Brother, told the story of an Iraqi family whose oldest son was killed by American troops. But in his new film, Delta Boys, he finds more than brutality or a simple parable of environmental destruction: he tells a moving, unsettling story about the teenage boys who are conscripted into the militant groups, and asks challenging questions about whether the guerillas are a force for justice or destruction.

Delta Boys is available for digital download on Tuesday, October 16, through Cinedigm Entertainment Group and through the Sundance Institute Artist Services program. In advance of the film’s release, Sage spoke with Andrew Berends about his time in the Niger Delta and the region’s ongoing conflict.

Sage: How’d you wind up interested in the Niger Delta? What’s the origin story of this movie?

Andrew Berends: Well, I had just made two films in Iraq, and I was looking for another exciting project. And one day I saw footage of the militants in the Niger delta — these big muscly guys, with their guns and their speedboats, and I thought to myself, Wow, that’s exciting.

That was the original hook, but then I did some research, and I realized what an important story this is. Not just in the Niger Delta, but also globally — it’s really about where our oil comes from, and the human cost of that oil. We use oil for everything we consume, and because we want it cheaply, people wind up suffering.

You begin the film by exploring these environmental issues, but then you seem to get captivated by the militants themselves, and life in their camps. The movie really changes directions.

To me, the experiences of people in conflicts are always most interesting. I don’t make the type of film where you go talk to an expert on one side, an activist on the other side, and a representative from Shell. It’s more meaningful to spend a lot of time with individuals, or with certain groups of people, and immerse yourself in their lives.

So how did you go about immersing yourself? The access you get is amazing — you see a woman giving birth, which is one of the movie’s most incredible scenes. Was it difficult to earn that kind of trust and confidence?

Initially it took a while. I actually went there one year, and after six weeks finally managed to get access to the camp. But then somebody in the camp changed their mind, and they left me alone in a village for a week. I was like, Forget this, this isn’t working, I’m going home, and I went back to New York. And for a year that bothered me — I kept telling myself that I should’ve stuck it out longer.

So I went back and I followed up with the same contacts, and the first night I spent in Ateke Tom’s militant camp, mainly because they didn’t have anywhere else to put me. Living in the camp was really uncomfortable: the food is terrible, there are mosquitoes everywhere. There was one journalist who once spent a night in the camp, but all the other news reports I’d seen were from journalists who spent two hours in the camp and left, and filed a five-minute report. So the fact that I was willing to live in the same conditions as them, eat the same food, mattered to them. I shared a mattress with six guys. It was awful, one of the most uncomfortable experiences I’ve ever had. To bathe, you get a bucket of water, and I was so inexperienced that I didn’t know where to start. I was like, so where do you soap up first?

Did you ever have the opportunity to go out with the militants when they left camp and went on raids?

I wanted to, but there wasn’t much happening while I was there. I was constantly asking them –– not that combat is the only thing that I find interesting, but it’s a big part of the story.

Then again, if you go with them, you’re going in a speedboat, and then you’re all in. You can always dive out of the boat, I guess, but that’s it. I had the same thing happen when I was in Iraq — I was in a couple of vehicles with the insurgents, and I hated that. I didn’t mind being on the street, even when they’re fighting, because you can always pull back around the corner and you’re okay. But if you’re in the vehicle and the Americans attack the vehicle, you’re stuck. And the same thing with the speedboat: if the Joint Task Force fights back, there’s nowhere you can go.

The reality of guerilla war is that there’s not always a lot of fighting. And that’s what makes life in the camp so interesting.

One of the most striking things about everyday life in the camps is that it’s pretty violent — there are some savage beatings and fighting amongst the militants themselves, and at times it’s hard to watch. What was it like for you to stand there and watch these defenseless guys get the crap beaten out of them, and why include that in the film?

The floggings were pretty intense, but it’s just military discipline being carried out. The second flogging in the film happened after one of the guys had his gun on his lap and accidentally fired it across the camp, and I was like—

“Flog this guy.”

Well, you need discipline, or someone’s gonna get killed, and it almost seemed appropriate.

When I’m doing this work, I kind of cut off emotionally in these kinds of situations, and then process it later. Still, there’ve been a few times when I’ve gotten emotionally engaged while I’m shooting, often when I see children suffering.

When I was in Iraq, I was filming a family inside a city, and their house was hit by a missile from an American helicopter. And this seven year old girl is telling her story, and she says she was sleeping next to her mother, and the missile happened, and she rolled over and tried to wake her mother up, and she didn’t wake up. And meanwhile the girl’s injured, and her brother’s injured, and I was — I wanted to explode, I was so angry. I get most emotionally connected when children are collateral damage.

It’s hard to draw the line in Delta Boys, though, between children and militants. A lot of the fighters are just teenagers who seem to have been seduced, or are in search of a better life.

There’s no question that the socioeconomic conditions are terrible. Young men have no opportunity for jobs, no opportunity for education, some of them don’t have access to food… and then suddenly there’s this opportunity to join the militants, who give them a place to sleep and three meals a day. It’s very clear that the overall situation in the Niger Delta is what’s leading them into the militant groups.

It also seems like they find the militant leader, Ateke Tom, very charismatic. What was it was like being around Ateke Tom, and did you get a sense of what makes him so beloved among his troops?

I don’t exactly know where his mojo comes from. The first night I was there, he was like, “So do you want to be a part of me?” And I said, “Well, I want to get to know you, but I also want to get know all of these boys as well.” And he said, “Well, they are me.” So I thought, well, that’s scary.

They use mafia terminology. He’s technically a don. They call him the Godfather. They think he’s the only guy who cares about them, so they’ll do anything for him, and he manipulates that.

Even before this Niger Delta struggle, he was already a gangster. He worked for politicians to help rig elections, and that’s how he got his money and his weapons. He’s responsible for a lot of people, too, though. There are people and families depending on him.

But it seems that by the end of the movie, the villagers have kind of come to hate and fear the militants.

The militants definitely don’t turn out to be what the villagers hoped they would be. And the villagers don’t want to get caught in the fighting. But it’s a symbiotic relationship — it’s not black and white. Sometimes the militants come spend money in the village, or give the villagers gasoline. And sometimes the militants are thugs and gangsters, and rob people on the creeks.

Even though the cause that they’re supposedly fighting for is completely legitimate, there’s a big question as to whether the militants are truly fighting for that cause, or whether they’re just fighting for a piece of the oil money. Because the militants also engage in bunkering, which is the sale of black market oil — which seems not that unreasonable, actually. It’s their oil in the first place.

Are they actually drilling for oil themselves?

No, they tap into pipelines. And the military is involved in that — because we’re not talking a few barrels here and there, it’s millions of dollars of black market oil changing hands, and that means there are tankers going into the creek and going out filled with oil. In some cases, when the military is fighting the militants, it’s because one side or the other is not getting their cut. The bunkering couldn’t happen without some cooperation from the navy.

The movie ends with the government and the militants negotiating a truce, with the government offering some social benefits—

Well, let me correct you. They offered amnesty for the militants, and they paid off the leaders. But what the militants were supposedly fighting for included actual development for the Niger Delta people — things like roads, and schools, and hospitals.

My argument is that nothing has changed, and nothing’s gonna change, and the militants just took they pay-off. The regular people, like the girl who gave birth at the beginning of the movie, are in the same situation as they were before, and the next boys who come around also have no opportunities for education or for finding a job. So nothing changes.

And it’s getting worse, because for these villagers and fishermen, their source of survival is those creeks and that jungle, and that’s being more polluted every year. There are over 300 oil spills in the Niger River every year, and they add up to more than the Exxon Valdez spill. Every year. And that’s in service of us — the world in general, but the West and the United States in particular — getting cheap oil. It always comes back to that.

[vimeo clip_id=”32161342″ width=”676″ height=”380″]