June 9, 2013

Delhi Slum Neighborhoods

On our second day in Delhi, the US PIRE students learned firsthand about the social and public health implications of poor urban infrastructure. Dr. Tapan Jyoti, a Peer PIRE participant sponsored by USAID, first introduced us to the director of a local office of the Gender Resource Center. The GRC supports women’s empowerment in the community through social, economic, and legal capacity-building. The GRC, which is physically located within the community, serves as a grassroots organization to connect women to government-sponsored health and economic incentives they may never even know about otherwise.

The women in the Brijpuri community participate in programs ranging from literacy training to entrepreneurial skills training, mostly in sewing. While these women have yet to develop a formal women’s group as has occurred in other slums, the Brijpuri women have developed an important social support network among themselves. The GRC director described several examples of visible changes in behavior and rising self-confidence among women and girls over the past 5 years.

The women in the Brijpuri community participate in programs ranging from literacy training to entrepreneurial skills training, mostly in sewing. While these women have yet to develop a formal women’s group as has occurred in other slums, the Brijpuri women have developed an important social support network among themselves. The GRC director described several examples of visible changes in behavior and rising self-confidence among women and girls over the past 5 years.

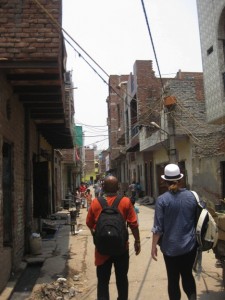

Dr. Tapan guided us through the narrow twisting streets of the Brijpuri slum. Honking motorcycles whizzed by every 30 seconds. We happened to visit the slum at noon, and the 110 degree heat made the complete lack of trees ever more apparent. On both sides of the street open drains carried sewage water. Kids played in the street, some lighting fire crackers to get our attention. Men and women stared out from their homes and shops at the group of foreigners, and we each felt a bit uncomfortable about how our presence in their community would be perceived.

After about 20 minutes of walking we reached the Najafgarh Drain which separated Brijpuri community from the Mustafabad community. The drain is lined by litter up and down its entire length, and a putrid smell wafts up from the water. This area is a severe public health threat for water borne diseases. In India, diarrhea alone causes more than 1,600 deaths daily. Hepatitis, cholera, dysentery and typhoid are other common ailments caused by contaminated water. The water in this drain will flow directly into the Yamuna River as we observed earlier on our Yamuna River Walk. A closer look at a map reveals that the Najafgarh Drain is actually a continuation the Sahibi River, which is channelized and collects sewage water once it enters Delhi. In fact, the Najafgarh Drain is known as Delhi’s most polluted water body.

We walked another 10 minutes through the Mustafabad community before stopping at the house of one of the women in the GRC’s women’s group. Dr. Tapan and University of Minnesota post-doc Dr. Ajay Nagpure translated as we asked the women about living conditions in the slum. Twice a day the women wait 30 minutes to collect drinking water from a well. Most homes have a toilet, yet sewage flows untreated directly to the drain. Several families at the meeting had experienced one or more cases of tuberculosis, typhoid or dysentery. The mothers’ biggest wish for their children is to get an education; however, many girls don’t attend school regularly due to safety issues. We learned, not surprisingly, that alcoholism among men and domestic violence against women are serious social issues that take precedence over environmental health problems in the slum. The response that probably surprised us all the most is that the families had no aspirations to leave Mustafabad. This is where they had established the security of strong social networks.

As we left the meeting one young woman asked Dr. Tapan “what’s going to happen for us now that you brought these people to visit?” This echoed our group’s discomfort in entering a slum community: what is our role as “outsiders” in studying their lifestyle and recommending changes? What positive and negative impacts will our presence invoke? Who are we to assume we know what’s “best” for this community?

These are ethical questions that social scientists have faced for decades. We spent a significant amount of class time this past week sharing perspectives from our diverse backgrounds in both the US and India. As scientists, engineers, urban planners, and public policy experts, we each have the opportunity to decide how our scholarly work should interface with the urban communities that are the subject of our research. Ramaswami , Zimmerman and Mihelcic (2007) present this summary of participatory action vs. conventional research in a paper entitled Integrating Developed and Developing World Knowledge into Global Discussions and Strategies for Sustainability. 2. Economics and Governance.

As a former Peace Corps Volunteer in Peru, I received plenty of training on participatory community-based project management. I know that this type of work is challenging. You will need to spend more time building relationships and trust in the community. You will face plenty of frustrations, language barriers and cultural misunderstandings. You may achieve much less than your original lofty expectations. Not everyone is cut out for activism or community-based work. However, I urge researchers in all fields, as well as the broader academic community, to consider deeply how their work could and should flow back to make a positive impact on their host communities.