When we moved back to Michigan, we bought an old farmhouse on five acres. I was still married then, with three young daughters and soon two more. After we had settled in, I planted an apple orchard.

The farmhouse was a white Greek Revival with four bedrooms and an old lilac out front. It stood on a barely perceptible rise on a dirt road running through the cornfields in the last pocket of open farmland east of Ann Arbor. It had only one immediate neighbor, directly across the road. No one knew exactly when the house had been built – the realtors had listed the date as 1900, which was realtor-speak for ‘we don’t know’ – but I found a depiction of the house in an atlas from 1854, and determined from records that the family who built it had purchased the land in 1830. I concluded it had been built sometime in the 1840s, like the other old houses in the area, presumably to replace a log cabin. The seller had given us a photo from the local historical archives of the house and its then-present occupants, standing in front, from about 1890. Some of the architecture had changed – the old kitchen wing and porch had been replaced with a two-story construction, and the big barn and windmill in back were gone – but most surprising was that the same big lilac was there in the same place out front, more than a hundred years before. Every time that lilac bloomed in spring, I thought of Walt Whitman’s poem, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” written on Abraham Lincoln’s death. I knew that the farmhouse had likely been standing there just the same way, with the lilac blooming in the dooryard, on the day that Lincoln died.

Like most old farmhouses, this one needed a lot of work, much of it to correct ostensible improvements made by previous owners. At least once the house had been abandoned. We heard from Mr. Graichen, a weathered old farmer up the road, that he had played in the vacant house as a boy, taking care not to fall through the rotten floorboards. Another old farmer, Mr. Vreeland, told us that the house had been used as a granary, and that his father, Dr. Vreeland, had bought it in the 1930s and renovated it into two apartments. Old Dr. Vreeland must have gutted the house down to the frame. All the old floors and ceilings and moldings were gone, replaced by factory-standard two-and-three-quarters-inch oak floors and sheet rock, and the only sign of a fireplace was the assemblage of boulders immediately beneath the dining room floor. The clapboard siding had been replaced with asbestos tile and vinyl. But the original post-and-beam frame remained, hand-hewn from what must have been old-growth oak, and under the whole main floor, visible from the add-on Michigan basement, were simple tree trunks, some with the bark still on. When we knocked out the sheet rock ceilings in the dining room and front parlor to expose the beams and had some electricians replace the squirrel-chewed wiring, the electricians complained about how hard the wood was – they could barely drill into it with their power tools. To have cleared the land of old-growth oaks and hewn those oaks into beams by hand with axes, the people who built that house must have been made of iron.

The five-plus acres around the house – essentially a 500-by-500-foot square – were bare dirt when we moved in. The seller had been leasing the land to Mr. Vreeland for farming. In late March, I traipsed across the muddy land to the southwest corner of the parcel and pounded in an iron stake with a sledgehammer next to the boundary marker. In the heavy wet soil, small pontoons of clay formed around my boots as I made my way out and back. My next task was to call Mr. Vreeland, introduce ourselves as new neighbors, and ask him not to plow our land in the spring.

The apple orchard began as part of a plan for a garden. As a kid, I had worked many hours in my mother’s garden, turning over soil with manure and peat moss, putting out cans of beer for slugs to drown in, harvesting beans and cucumbers and cabbages, and tending vaguely to a number of dwarf fruit trees planted along the perimeter inside the picket fence. As a teenager, I had graduated to my grandfather’s commercial orchard, picking apples and tart cherries and pears, high up on a three-legged ladder with a canvas basket on my chest. Now, I thought, I would put in two garden beds and five or six fruit trees, as my mother had, in the open dirt just south of where the grass ended around the house. Then I discovered there was a price break when you ordered fruit trees online. I could get six fruit trees for $150, or forty-two for $460. The choice was easy. I went for the forty-two, and the orchard was born.

I had a lot to learn about apple orchards. I learned, for example, that apples didn’t grow true to seed. This meant that if you planted an apple seed, the tree that grew from it – far from being the same kind of apple it came from – could be any one of thousands of varieties. Apple trees were kind of like children that way. Some resembled their parents, but others took after any one of myriad ancestors, known or unknown. There was no way to tell in advance. Apples therefore had to be cultivated (unlike children, at least at this writing) by taking cuttings from a known variety of tree, grafting the cuttings onto rootstocks, and planting the grafted trees.

Rootstocks, in turn, controlled the size of the tree. Dwarf trees were dwarves because they had been grafted onto an only weakly vigorous rootstock; full- or standard-sized trees grew full-sized because they had been grafted onto very vigorous rootstocks. Dwarf rootstocks, it turned out, being only weakly vigorous, tended to suffocate or drown in heavy clay soil. Dwarf trees also stopped growing at six or eight feet and became exhausted and had to be torn out and replaced every ten or fifteen years. Standard trees, by contrast, could grow to thirty or forty feet and live for many decades. That was another easy choice. I settled on Antonovka, a standard Siberian rootstock that was extremely vigorous and cold-hardy down to minus twenty-five. I wanted my orchard to live for a hundred years.

The next step was to order trees. Most apples trees, I came to understand, were not self-pollinating. At least two varieties were required in order to cross-pollinate, and as a necessary corollary, they both had to bloom at the same time. Some apples bloomed early, in late April or early May, which in Michigan would increase their vulnerability to frost; others bloomed in mid- or late May. I scrutinized the online bloom-time chart and settled on three initial varieties which would bloom more or less concurrently in mid-May: Cortland, Jonathan, and Honeycrisp. Years later, after the trees had begun bearing fruit, I tried to sell these three varieties at a local farmers’ market. Everyone knew Honeycrisp, but only a handful of people had ever heard of Cortland, and at least half a dozen people asked me if the Jonathans – which were properly small and dark – were plums. Meanwhile, at the other apple vendor’s table down the row, his bland supermarket varieties, which he hand-polished with a cloth, were selling faster than he could polish. I would need to find another revenue model.

Now I had to lay out the orchard. On the bare dirt, I marked with stakes and twine, and then dug out with a shovel, forty-two small round holes about eighteen inches deep, on a somewhat old-fashioned spacing of twenty by twenty-five feet. The mature trees couldn’t be too close, or they would rub branches, and it would be difficult to get a tractor through. In late April, the initial round of forty-two dormant trees arrived by UPS, tightly packed in a tall box, from the nursery in Pennsylvania. I took the day off and planted. The trees were an inch-and-a-half caliper at the trunk, about five feet tall, with bare roots. They were feathered, meaning the branches had been pruned into an initial set of scaffoldings. The young bark of each tree had a different cast: the Cortlands blackish, the Honeycrisp golden, and the Jonathans a deep red. Forty-two times, in accordance with the instructions, I trimmed the roots with a scissors to fit the size of the hole, filled in the hole around the roots with soil, watered the planted tree with the running hose, and stamped down the wet clay earth around the tree to get rid of air pockets. After all the trees were planted, I mulched each one with a thick layer of wood chips to prevent weeds from growing above and tender new roots from drying out below. And around each tree, I cut, wired together, and staked into the ground a cylinder of farm wire fence about five feet tall and four feet in diameter, to protect against the deer. It was twilight before I was done, but I turned back and surveyed my handiwork: where there had been bare dirt, stood six neat rows, in geometric pattern, of slender trees and wire cages. The landscape was transformed. In the place of nothing, there now stood a young apple orchard. Not only did we live in a farmhouse; we now lived on a farm.

The next day I sprayed for the first time. A thin layer of so-called dormant oil on the bark, before the trees began to bud out, would suffocate insect eggs and moth cocoons and any other small lurking pests awaiting spring. When I sprayed the trees by hand from my new backpack sprayer, I was surprised how they gleamed and glistened, each in its own different raiment, as if anointed, as if christened with beatifying oil.

Deer were a constant menace. I soon discovered, based on their hoofprints, that a deer trail lay more or less diagonally across the land I had planted, from the dirt road in front to an old hedgerow at the back corner of the property. Once, in the high grass toward the hedge row, I found the carcass of a young buck. I guessed it had been hit by a car and lain down there to die. The carcass had been largely scavenged by coyotes, but the antlers, among other things, remained; it had been a six-pointer. I gave the antlers to the children, who took them to school for show-and-tell. When the trees leafed out in spring, deer would stop by each tree along the trail and tear off the tender leaves and tips of any branches that had grown through the farm wire fence. Rabbits, when they ate things, would snip them off cleanly and sometimes just leave them lying on the ground. Deer, however, did not snip; they pulled and tore. And each time they tore, the torn tree tip responded by forking, so that two new tips grew forth in place of one, and the terminal growth of the branches was distorted, and eventually the structure of the mature tree would be deformed.

I had mixed feelings about the coyotes. On the negative side, they were threatening; we often heard them out in the fields yipping and yowling in the middle of the night, always sounding like one had just turned up with a fresh kill. And there were other times during the day when they came in through the high grass close to the house when the children were outside playing, making stick houses or floating little boats in standing water in the orchard. Once, when my wife took Buck, our yellow lab, out the back door first thing in the morning, not thirty feet away from the house stood a lone coyote, intent on the two barn cats perched on the back steps. Buck had given chase, and the coyote had run, but when my wife succeeded in calling Buck back to the house, the coyote turned around and came back too. My wife thought maybe it was a lost dog in the neighborhood, but one look was enough. I went back inside for the .22, but when I came out, the coyote was gone. Mental note: when dealing with coyotes, bring the .22 out the first time.

For fruit-farming purposes, though, the coyotes had a positive side: they didn’t eat crops, and they threatened mainly deer and rabbits. I was out early one spring morning when I heard a strange noise coming from across the fields to the south. Running across the bare ploughed earth at top speed toward the far treeline was a fawn, bawling at the top of its lungs, with a coyote in hot pursuit, and right behind the coyote, a full-grown and very determined doe, no doubt the fawn’s mother. First the fawn, then the coyote, and then the doe disappeared into the thicket. A moment later, the doe emerged with the fawn, and they trotted away, shaking themselves off, as it were, and heading home. I didn’t know what happened to the coyote. The fawn would live another day, but the episode confirmed what I already knew: beyond the boundaries of the orchard, it was survival of the fittest.

That fall and winter I fenced the entire property. In October, I measured and staked every twenty feet along the property line, except immediately in front of the house, where there was already a fence. I rented a stand-up hydraulic auger and drilled eighty-some holes for fenceposts. The fenceposts were ten-foot pressure-treated four-by-fours, so that about seven feet would remain above ground. I knew that seven feet would be nothing to a deer – up north, deer fences around the orchards were ten feet, if not twelve or fourteen – but it would be better than no fence at all, and it might keep the coyotes out. I put the posts in the ground, braced them horizontally at intervals, and then set about the long process of stretching and nailing the wire fence. By March I was done. Only once thereafter did I ever see a deer inside. I was taking the kids to school in the morning, wearing a suit and tie, and as we came out of the house, I noticed a big buck casually moving along the old trail through the orchard. I gave chase with an umbrella, and the buck sauntered away and with one leap sailed easily over the fence, with room to spare. Deer were generally creatures of habit. I saw a show on TV once about a Neolithic hunting site consisting of a long line of boulders. The deer were in the habit of walking along that line, and the early humans would lie in wait there to hunt them, hence the archaeological site. In the same way, the deer formed the habit of walking the line of my new fence; it never seemed to occur to them to just leap over. Lots of things occurred to the coyotes, though. I had to shore up the fence regularly to keep them out.

With the fence up, I put in more trees. Every spring for the next four years, I ordered and planted another forty-plus trees, until I’d reached two hundred, and the orchard took up three acres, and I’d run out of land to plant. At first, the kinds of apples I planted were unfamiliar. There had once been thousands of varieties, but now only ten – good-looking, good-storing, and bland – held ninety percent of the commercial market. My plan was to grow old-time apples for fresh eating but also for hard cider. We all knew the story of Johnny Appleseed, but what we didn’t seem to appreciate was that Johnny Appleseed was less about apples than alcohol. Hard cider was the original American drink. Water wasn’t safe, and the Germans had not yet arrived with beer, so even John Adams, that pillar of New England sobriety, reputedly drank a tankard of hard cider every morning at breakfast. Every old farm had an apple orchard – the 1854 almanac that depicted our farmhouse also depicted an orchard immediately to the north – whose primary purpose was to produce hard cider. You had to plant forty seeds because the apples would all come out different; a few would be good to eat, some would be good for hard cider, and the rest might be good only for livestock. But if you planted forty trees, you probably had it covered. The hard cider market in the U.S. was now just beginning to take off, like craft beer ten or fifteen years before, and I thought I might be able to make a small business out of it, selling the apples or even making hard cider myself.

So the following spring, I planted rows of old apples with exotic-sounding names: Esopus Spitzenburg, supposedly the favorite of Thomas Jefferson; Roxbury Russet, the oldest American apple, recorded in the 1600s in Roxbury, Mass.; and Yarlington Mill, a golden-yellow English hard cider apple known as a bittersweet – bitter for all the tannins, and sweet for all the sugar. I planted Kingston Black and Foxwhelp, both English bittersharps, full of tannins and acidity, and Winesap, an old American hard cider variety, as the name implied. Finally, I planted Dabinett, another English bittersweet, and the old English Ashmead’s Kernel. Many of the old apples were strangely shaped – ribbed, conical, oblong – or had russeted leathery-looking skin, or were very dark or “black” in the old parlance, and would never have sold in the supermarket, with or without any amount of professional polishing. But they had remarkable variety and flavor. The hard cider apples, like wine grapes, tasted bad and you couldn’t eat them, but the qualities that made them taste bad fresh were the same ones that made good cider.

Before each new planting, I mowed another portion of the property with our small tractor and was always astonished, and sometimes appalled, at what emerged from the high grass. The first thing I realized was that everywhere, there were voles. Voles were the deluxe version of field mice, except that they were homelier and hungrier and lived above ground or tunneled under the snow in winter, without hibernating, and liked to chew the bark off tender young apple trunks, thereby girdling and killing the trees. I confess, I ran the voles over with the mower whenever I could, or even jumped off to stomp on them when they threatened to escape. There were other creatures, too. For weeks there had been a pair of harriers, flying low and hovering over the fields in search of prey. They disappeared after I mowed. Another time I had mowed part of the field down to maybe a twenty-by-twenty-foot square, when I saw something move out of the corner of my eye. Initially I thought it was a red squirrel, but it was too long and slinky and too far away from the black walnuts near the house. It shot off into a hole next to one of the fence posts. I looked it up in a book, and it turned out to be a long-tailed weasel, with a red back in summer and white in winter. Its primary food was voles. I had never seen a weasel before, but that explained a number of curious things around the house, for example, how a robin’s egg had wound up, intact, one morning on a railroad tie in the garden: I had wondered what creature could possibly have carried it there. After I mowed, though, I didn’t see the weasel again either.

In spring I paid attention to weather. As the trees matured and began to bloom, I was on the lookout for frosts. A hard frost during bloom could wipe out the entire crop. The difference between a light frost and a hard frost was surprisingly slight; as I read on the state university’s agricultural extension website, kill rates for apple blossoms, depending where they were in the bloom cycle, were something like ten percent at 27 degrees and ninety percent at 25 degrees. Two degrees made all the difference. Now I understood why orchards were so often planted on hills, and why our old farmhouse, though only on a low rise, stood on the highest point around; the higher elevation, even if only twenty or thirty feet, was worth a few degrees, which could mean having or not having an apple crop. Up the dirt road to the north, where the land dipped down into a low-lying little swamp, on winter days with no wind, I watched the temperature on the car thermometer drop 15 degrees. The bottom of a hill was no place for an orchard.

I sprayed the trees when the first green leaf tissue appeared. I used ionized sulfur for apple scab, a leaf blight that also caused big soft spots on the mature fruit; bacillus thuringiensis for caterpillars and moths, a bacteria that rotted out caterpillar gut systems and nothing more; and pyrethrin, made from chrysanthemums, for flying insects such as apple and plum curculios that bit and disfigured the soft young applets. It was hard to know where the blights and insects came from; some, I suspected, came from the road, carried on vehicles, but once an infestation of potato leafhoppers blew in from hundreds of miles away on a summer storm.

Spraying soon became a challenge. My backpack sprayer was enough for a year or two, and then I switched to a 40-gallon tank on the back of the tractor, but the 40-gallons eventually became 80 and then 120 and took hours and hours to complete. I didn’t imagine that sulfur was particularly healthy, even if organic, and I didn’t spray pyrethrin during bloom time because it would also kill the bees. I wasn’t convinced that spraying made a huge difference; some of the trees, like Honeycrisp, looked awful no matter how much I sprayed. Honeycrisp had been bred in a university lab in Minnesota and chemically speaking, needed the whole nine laboratory yards. Eventually I reduced my spray regime to the two weeks after petal fall, when the young applets were soft and vulnerable, until finally I didn’t spray at all. A hundred years ago, I thought, no farmer had sprayed the apple orchard, but somehow they’d still had fruit. The results of my experiment were not pretty. I still had fruit, but I understood why old-time students had brought that perfect apple to their teacher; in the whole orchard, there might not have been more than one.

One summer I added compost to the trees – thirty cubic yards with a wheelbarrow – and every summer I watered. The Antonovka rootstocks developed a deep taproot, so only the first-year trees really needed watering, especially in July and August, when the grass dried out and the ground baked hard and the clay soil looked all cracked and fissured on the surface. I bought two hundred feet of garden hose and paid my second daughter a dollar a tree, and she would set her alarm and every fifteen minutes, ride her bicycle out into the orchard to move the hose.

In early fall, with my daughter’s help, I painted the tree trunks white, with water-based paint, up to about three feet high to protect against sun-scald and keep off the rabbits. Sun-scald happened on sunny days in winter when snow reflected the sunlight onto a dark trunk, which then absorbed the light and grew warm until the sap inside began to flow. At night, though, the sap would freeze again, and the bark, or even the trunk itself, would split open. The white paint would reflect the sunlight and keep the sap from getting warm. Against rabbits and other gnawing rodents, paint was only moderately effective, as an initial bad taste, presumably. I also put a farm wire guard around the trunk of every tree, until the trees grew big enough that the bark got thick and hard and was no longer edible. One year I misjudged and removed the wire guards, since grass and weeds grew up around the trunks inside them, taking up nutrients and providing cover to pests, and the trees soon paid the price: in late winter, rabbits gnawed through the bark on nineteen trees, though none was entirely girdled. To my surprise they all survived.

I waged an ongoing war against the rabbits. Sometimes you wouldn’t see one all summer, because the coyotes were on the rise, but other times, in spring in particular, the property was crawling with them. At night, we would hear the rabbit males fighting on the grass outside – as animal sounds went, a rabbit scream was hard to forget – and the barn cats would catch the newborns, toying with them until they felt like making the kill. The mother rabbits often nested in the high grass, and several times, without knowing it, I mowed right over a nest. The mother was always gone, and the mower blade was set high enough that none of the baby rabbits was struck, but they were often stunned, as if from the percussion, and milled around for a few moments in confusion in the open in the short cut grass. I knew they would grow into destructive pests, and part of me wanted to dispatch them on the spot, but I thought – perhaps only out of pathos – that even a noxious rabbit deserved to live, to exist in the world, for more than a day or two. I picked the baby rabbits up in my gloved hands and brought them to my young girls. One year the girls fed two very small baby rabbits milk from an eyedropper until they had been nursed back to apparent health. We dropped the young creatures off in a nearby nature preserve, where they were left to their own resources. My only hope was that they wouldn’t find their way back to the apple orchard.

There were other predators in, or above, the orchard. One year I saw an eagle, flying straight-winged to the north over Vreeland Road, being harassed by crows, which looked tiny, pecking its wing-feathers. Another time I watched a falcon circle high up, then, unexpectedly, fold its wings and plummet to the ground. At night I heard screech owls – the bird book described their call perfectly as a “tremulous descending wail” – and bigger owls hooting portentously in the hedge rows between the fields. And the prehistoric cry of the sandhill cranes reverberating across the landscape always made me feel like I lived far out in the timeless wild.

I had to watch carefully for crows. As August passed into September, I would find an apple here and there that had been pecked. Casualties were only a handful, I thought, and no cause for concern. One evening in mid-September, however, I returned home to find the greater part of my small apple crop destroyed. A flock of fifteen to twenty crows had been sighted. Apples had been blasted open and knocked half-eaten to the ground. Some trees had been effectively cleared of apples, and almost all of my biggest and reddest specimens were gone. The Honeycrisps and Cortlands, which were closer to harvest, had been hit especially hard, while many of the Jonathans had been pecked once, disfigured, then left alone. The crows, it seemed, had gone for the riper, sweeter apples and passed over the still-tart Jonathans. A disturbing thought occurred to me: the handful of ruined apples I’d found in August had been probes. Crow scouts had been taste-testing my apples to determine whether they were ripe. Their mid-September raid, rather than being chance, had been carefully planned and timed, as I had labored on in oblivion. The crows were smart, alright. They were also smart enough to remember that I started shooting at them after that when they showed up, even if only with a (generally) unloaded pellet gun – they didn’t know it was unloaded, but they knew it was aimed at them, and eventually they kept their distance.

In winter the orchard was quiet, but February and March were pruning time. On a tree, pruning created small wounds wherever a shoot or branch had been cut off. The theory was that in February or March, the wounds would have the shortest time, and the least exposure to pathogens, until they could start healing when the trees broke dormancy in April. Some people also pruned in August, but that struck me as ill-advised; with the August heat and rain, populations of dangerous bacteria like fireblight could explode, and an August pruning could introduce the bacteria into the trees. The rationale for pruning was to build a series of scaffoldings of branches on the trunk, or central leader, of each tree, with at least three or four feet between each scaffolding, to ensure enough air and sunlight in the interior so as to avoid disease and promote larger fruit. Branches were ideally at a 45-degree angle from the trunk; an angle too acute or too obtuse would put branches at risk of breaking under a heavy crop. It was odd, somehow, but if left to their own devices, the trees would grow in ways that were harmful – downwards, or into a candelabra, or inward into themselves into a gnarled-up shape that created perfect conditions for pests and pathogens, so that the resulting apples, if any at all, would be small and pitted. Perhaps nature cared only for the seeds and the continuance of the species, and not for the individual tree, long life, the unbroken branch, or the large and beautiful fruit. But that was my job. In the orchard, that was my reason for being, to care for and protect each individual tree, to see that each one survived and grew and bore its best and most beautiful apples. Nature cared for all its creatures, for the deer and the rabbits, the voles and the crows, the caterpillars and curculios, the bacteria and fungal blights, and wanted them all to survive. You just had to decide which part of nature you favored. I was an orchardist, and I knew which part.

So I learned to prune. I made mistakes along the way. At first I was afraid to prune much of anything. I thought that as the trees grew, the branches would be carried upward with the trunk, like enlarging a photo on an iPhone. But that wasn’t how apple trees grew. A branch that was three feet off the ground now, when the tree was five feet tall, would still be three feet off the ground when the tree was thirty-five feet tall; if the next scaffolding was two feet higher than the first one, it would still be only two feet higher. The trunk grew upwards, alright, but the branches stayed where they were, and just grew thicker. I had to cut out prodigious amounts of wood, which I stacked in piles, and hauled off to a growing brush heap, and eventually doused with diesel fuel and burned in a giant pile like an offering. The rule of thumb was that you weren’t supposed to prune out more than one-third of the tree in any given year, but I’m sure with many of them, I pruned out half. And then I learned another lesson. If you didn’t prune the trees enough, they became vulnerable to all the pests and pathogens arrayed against them, but if you pruned too much, you provoked a counter-reaction. They grew like mad in all the wrong places, sending up suckers from the ground and soaring vertical watersprouts from every branch and multiple shoots and twigs from every pruning cut, until the structure you were aiming at was overwhelmed by a riot of furious, and fruitless, vegetation. It might take a year or two of pruning the trees very lightly just to calm them down.

Each kind of tree had a different habit. The Jonathans had a so-called weeping habit, where the branches would bend, or weep, towards the ground. One year I had a bumper crop, and the fruit was so heavy on the Jonathans, some of those weeping branches broke under the weight, including one of my central leaders. The Yarlington Mill, by contrast, grew pencil straight, upwards and outwards, which made pruning easy, while the Kingston Black were tough and knobby and liked to grow into a candelabra of long knuckled woody fingers. I was surprised once to see my own tracks in the snow, circling around a tree, as I tried to envision its pruning future.

When the pruning was done, in March or April, I put out houses for non-social bees. Everyone knew about honeybees and their problems, but there were multiple species of wild bee that had nothing to do with honey and popularly, at least, were more or less unknown. These bees were non-social because they didn’t live in a hive. Since they didn’t live in a hive, they didn’t produce honey, and since they didn’t need to defend their honey, they didn’t really sting. They would lay a single egg in a hole and provide it with a pollen ball and seal the hole up with some kind of substance, depending on the bee. Mason bees would use mud, leafcutter bees would cut a neat little circle out of a leaf, and grasscutter bees stuffed their holes with grass. The thing was, all the wild bees were far better pollinators than honeybees. Honeybees were apparently quite fastidious about cleaning themselves, while the wild bees were content to be scruffy, which meant they were covered in pollen and much more likely to pollinate. The trick with the houses was to drill a hole, or buy a cardboard tube, of just the right diameter, about 5/16 of an inch; if the hole was a fraction too big or too small, you might get nothing, or possibly a different bee species. If you did it right, by September or October, the holes would be plugged with mud or a cut-out leaf or a little clump of dried grass. And the following spring, at bloom time, your pollinators would be on the job.

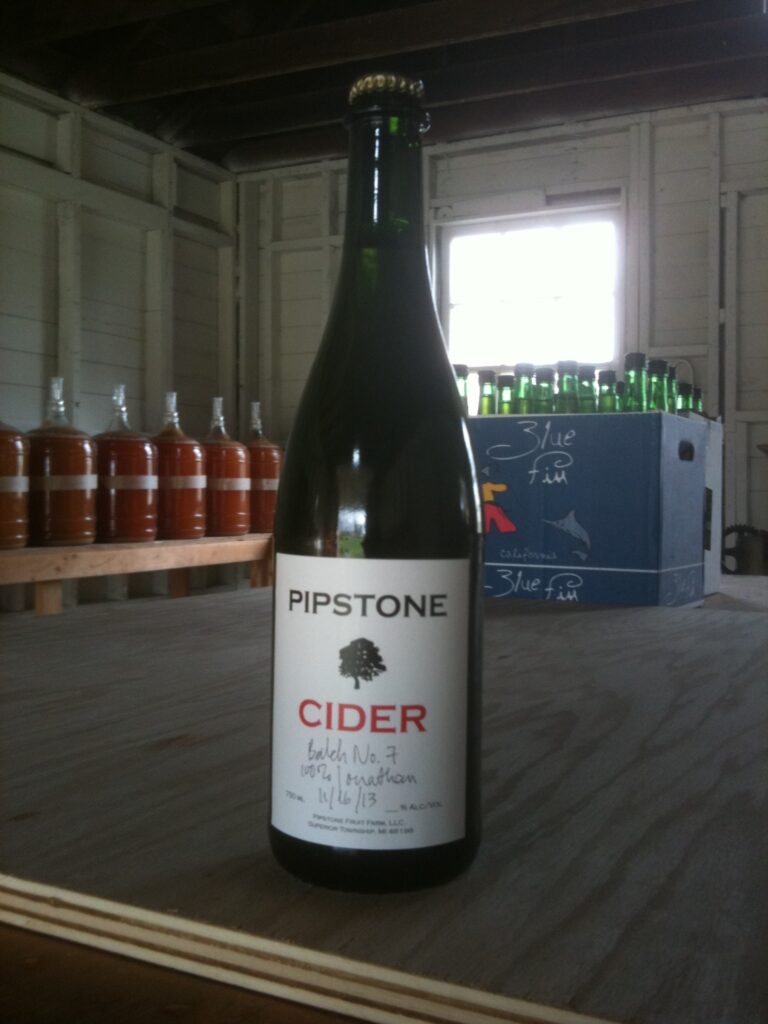

My trees at last began to bear fruit, first the older varieties, and then the more recently planted ones, in fits and starts, but in greater quantities each year. The trees grew taller, and the property began to look like a regular orchard. I bought crates and a ladder and a canvas picking bag, and with my now teenage daughters’ help, picked the fruit over a series of weekends. We soon had an outbuilding filled with the faintly winey fall scent of ripening apples. I rigged up a shop press and bought racks and cloths and glass carboys and champagne yeast, and soon had a hundred gallons of cider fermenting out to dryness, bubbling carbon dioxide out through the airlocks. Months later, when the fermentation was done, I bottled the cider in champagne bottles and made up a label and even formed an LLC. The cider was clear, golden amber in color, with soft tannins and bright acidity, and a flavor as if the apple trees had a soul, and they were communicating it to us in the cider. In all the wide world, that cider had never been anywhere else; it passed in and out of being on our small farm.

The following summer I fought an outbreak of fireblight. Fireblight was a bacteria that, once it got into the trees, would cause the terminal shoots to desiccate and blacken and curl downward into a tell-tale shepherd’s crook. If the infection went unchecked, it would move down the branches into the trunk until the whole tree dried and blackened and oozed and looked as if it had been burned, hence the name, “fireblight.” Most bacterial and fungal blights were a nuisance; they would weaken the tree and spoil the fruit, but nothing much worse. Fireblight was different. If it got into the trunk, it would kill the tree. If it infected one tree, the entire orchard was at risk. The orchard could be wiped out in a single summer. In the orchard, fireblight was what I feared most.

It struck first among the Yarlington Mill. Optimal conditions for the bacteria, as I learned from the agricultural extension website, were a combination of high heat and heavy rains. The bacteria multiplied from a few dozen or a few hundred on a leaf or branch surface into hundreds of millions in a matter of hours. Highly infectious, they dripped and ran down the branches with the rainwater and were blown downwind onto other trees, where the process repeated itself. Yarlington Mill were evidently susceptible, though based on the locations of the first infections, I concluded the bacteria had entered not through my pruning cuts, but as the trees had bloomed, through the openings of the white blossoms. I knew it was only botany, but I found it morally offensive: the most delicate and beautiful moment in the trees’ lives became a vulnerability, an opening by means of which the fireblight could infect and kill.

I set out to prune out the infected parts of every tree. This treatment was not without risk, since each pruning cut would leave behind a potential new infection point, and even worse, because the pruning shears themselves, once exposed to the bacteria, would become the primary vector for spreading it further down the branches and into other trees. The only counter-measure was to dip the pruning shears in bleach after every cut. I went out every day I could for weeks with my pruning shears and small bucket of bleach and cut out every infected branch, not only among the Yarlington Mill, but now also here and there on the Winesap, Esopus Spitzenburg, and Jonathans. When cold weather finally came, I breathed a sigh of relief. But the next spring I saw the telltale shepherd’s crook among the Yarlington Mill once again, and the blackened oozing bark, this time much deeper into the trees. Pruning was no longer an option. The Yarlington Mill soon looked like they’d been scorched by fire. I went out with a handsaw, and one by one along the row, reluctantly cut them down.

I didn’t know it then, but that summer was the beginning of the end of my apple orchard and my life with my young family at our old farmhouse. I wasn’t able to contain the fireblight, and then the divorce happened. I had to move out of the farmhouse, to a rental place in town, and the trees had to fend for themselves. One by one, the girls went off to college, and as they grew into adulthood, our lives, naturally enough, went their separate ways. I eventually took a job out of state and left Ann Arbor. My ex-wife sold the house.

Years later, on a fall football weekend, I drove out to see the old place, and I had trouble finding it. The whole area had developed, and the roads were crowded, and on the corner of our old road were traffic lights and a chain drugstore and an office complex with parking lots. The dirt road had been paved, and instead of hedge rows and cornfields, there were curbs and sidewalks and sprinklered lawns, and when I got to where our property had been, the farmhouse and the lilac and the apple orchard were gone. Instead, there stood rows of multi-gabled vinyl houses with attached garages and driveways and paved subdivision roads. I had trouble even recognizing the lay of the land, until I realized it was part of a larger parcel now, and they had re-graded everything flat for the subdivision.

Next to one house, though, toward the back, I noticed a single tree, untended and overgrown, but heavy with small fruit. The tree was at least thirty feet tall, with an upright habit and pencil-straight branches and golden-yellow apples, and I knew it was a Yarlington Mill. It had become merely part of the landscaping, and was probably considered a nuisance by its owner, given that it littered the ground with small, bad-tasting fruit. Years before, in that summer of fireblight, when I had cut down the Yarlington Mill, I had left the two-foot stumps in the ground, on the expectation that I’d pull them out the next spring, after the roots had released their hold, and the work had become easier. But to my amazement, when spring had come, every one of the stumps had sent up prodigious new suckers, and they were soon eight feet high, each one, after pruning, with a strong new central leader. I supposed it made sense; the whole root system had been intact to support new growth above ground, and apple trees, being tough, didn’t easily give up the ghost. Still, for a moment it had seemed as if the dead had come back to life.

I got back into the rental car and drove to the airport. I wished I had roots like my old apple trees, deep enough to withstand life’s fireblights and even the inevitable handsaw, but I had only what I was able to hold onto within myself. The rest seemed to get swept away by the ever-rising tide of the world around us. In the end, I knew that tide would wash away the traces of our lives entirely, until the once-rooted land was covered by a strange new sea, and only memory remained, a slender cord, to bind us to ourselves.

I couldn’t bring myself to let go of that cord, even as it frayed.