Khalil and I constructed a plan. We agreed to first focus on retrieving the cameras that had the best potential for capturing snow leopards. If we hurried, we might still be able to beat the mountain travelers to most of our locations. But Khalil also prepared me for disappointment. “We have probably lost a third to half of our cameras,” he warned. Before daybreak the following morning, we packed maps, GPS units, and a week’s worth of food and headed back out to our study area. I prayed that we weren’t too late.

The area had changed dramatically in six weeks. Where there had been endless snow before, great fields of flowers and grasses now covered the foothills and surrounding mountainsides. Thick patches of alpine shrubs concealed formerly barren ridgelines and drainages. Rivers and streams that had raged with spring runoff now flowed softly in the valley bottom. Picking up the cameras was a lot easier than placing them. The GPS coordinates took us straight to each one, though some were hard to find among the new array of tall, leafy vegetation.

Each time I found a camera I wondered, “Is this the one? Did a snow leopard walk by here?” A strong sense of optimism kept me going, but I tried not to let my hopes get too high. There were many mountain peaks and the range was so vast that the chance of even one snow leopard passing in front of any of our cameras was minuscule.

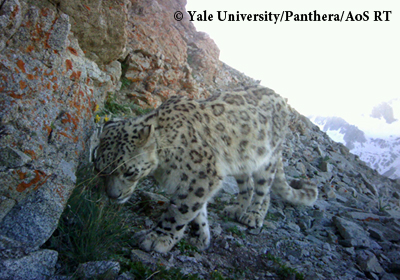

We were on the final set of folders from the last Karatag camera when it appeared. Its pelage was so well camouflaged against the speckled rocks that I had to look twice to be sure. But Khalil and Zayniddin saw it immediately. They jumped out of their bags and whooped and cheered into the cold night’s air. My eyes darted back and fourth between them and the snow leopard on my screen. It was beautiful. It had massive paws and a long, thick, spotted tail. The five images–captured a fraction of a second apart–showed the adult cat sniffing where an ibex had been seen days before. Khalil came over and patted me on the back. “Congratulations, Tara! You are the first to confirm snow leopard presence in this range,” he said. “We did it!” I said. I knew I couldn’t have done it without them.

I had to return to the U.S before all our cameras were retrieved. My assistants finished the fieldwork and found that our cameras had photographed two more snow leopards.

These pictures are just the beginning. The DNA results of the scat samples we collected will provide even more data regarding snow leopards in Tajikistan. The presence of snow leopards in the Hissar range indicates it is part of a landscape that connects crucial wildlife habitat and snow leopard populations in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Our data also suggests the need for a sustainable wildlife management plan to help protect snow leopards and Siberian ibex, their primary prey.

I am excited and hopeful for the future of wildlife conservation in Tajikistan. I am thankful for the opportunity to add my small part to this cause, but the many family members and Tajik people who contributed to our investigation, and especially researchers like Khalil and Zayniddin, are the true conservation heroes.