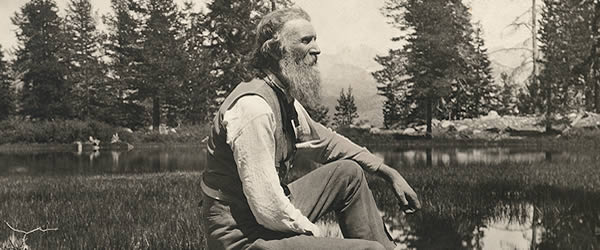

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” – John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

This comment, by the matchless John Muir, sums up my graduate school experience.

I matriculated at Yale as a joint degree student between Yale Forestry & Environmental Studies (F&ES) and Yale School of Public Health. Partway through my first year, I shifted from public health to the School of Management to pursue an MBA, and changed my F&ES Masters of Environmental Management degree to a Masters in Environmental Science. My resulting Masters thesis is decidedly a fusion of environmental, public health, and business concepts. The two degrees I just graduated with are very different from the two I started with originally.

Indecisiveness? I don’t think so. Really, it goes back to the quote from John Muir. The more I learned, the more I saw connections. Big problems, like climate change and global health, are not simple; they are inherently complex, which is why they are so difficult to solve. They have many causes and, thus, require many solutions. Attacking these most complex of problems requires us to look outside one discipline – to look upstream, or downstream, or maybe in the town next door – for answers.

My thesis sought to spark connections by exploring the relationships between trees, crime, and health in New Haven. A growing movement in the US explores the positive effects of nature on health. Robert Ulrich was one of the first to empirically study these relationships. His 1984 study found that hospital patients recovered from surgery faster when placed in a room with a window view. Research has continued since then, and interaction with nature has been positively connected to health through improved air quality, physical activity, social cohesion, and stress reduction. Researchers from varied schools of public health, urban planning, architecture, forestry, and health care economics have come on board, adding to the research, influencing policies, and enacting programs to align health and conservation fields. The American Public Health Association (APHA), the world’s largest organization of public health professionals, recently joined this coalition, releasing a policy statement titled “Improving Health and Wellness through Access to Nature.” Of course, there are still many nuances and underlying complexities to solve. How can we measure one’s exposure or dosage of nature? How can we address underlying socioeconomic drivers that also have a major impact on health?

Which brings me back to my activities this summer. My research grew out of a grant from the Center for Business and the Environment at Yale. Bringing together researchers from across Yale, we are working to apply the university’s research powerhouse to build out the academic portion of this movement. The project convenes professionals from differing disciplines to answer some important questions. How does exposure to the natural environment relate to the health outcomes of New Haven citizens? What are the possible reductions in health care costs and possible gains in worker productivity associated with increased access to the natural environment? What mechanisms might explain the associations between access to the natural environment and physical and mental health? By finding links between nature and health, we can add another point to the business case for investment in nature: dramatic cost savings in health care.

I have spent June preparing our first findings for publication. The journal we are targeting – Landscape & Urban Planning – is not a normal publication venue for the project’s public health or forestry researchers. The fact that the journal is unusual for both parties speaks to the complexity of a topic that defies anyone who tries to pick out just one part by itself, giving credence to the sentiment John Muir expressed over 100 years ago.

For further reading on the nature/health nexus, check out the following resources:

“If You Live Near a Park, You’re More Likely to be Happy.” Ben Schiller, 2014. http://www.fastcoexist.com/3029115/if-you-live-near-a-park-youre-more-likely-to-be-happy

“When Trees Die, People Die.” Lindsay Abrams, 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/01/when-trees-die-people-die/267322/

Beyond Toxicity: Human Health and the Natural Environment, Howard Frumkin, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11275453

The Powerful Link Between Conserving Land and Preserving Health. Howard Frumkin and Richard Louv, 2007. http://atfiles.org/files/pdf/FrumkinLouv.pdf

Designing Healthy Communities. PBS Series, 2012. http://designinghealthycommunities.org/

Edited by Amy Weinfurter.