After recent fires at Great Smoky Mountain National Park, Elizabeth Parker Garcia reflects on the mountains of eastern Tennessee as a place of loss, remembrance and resilience.

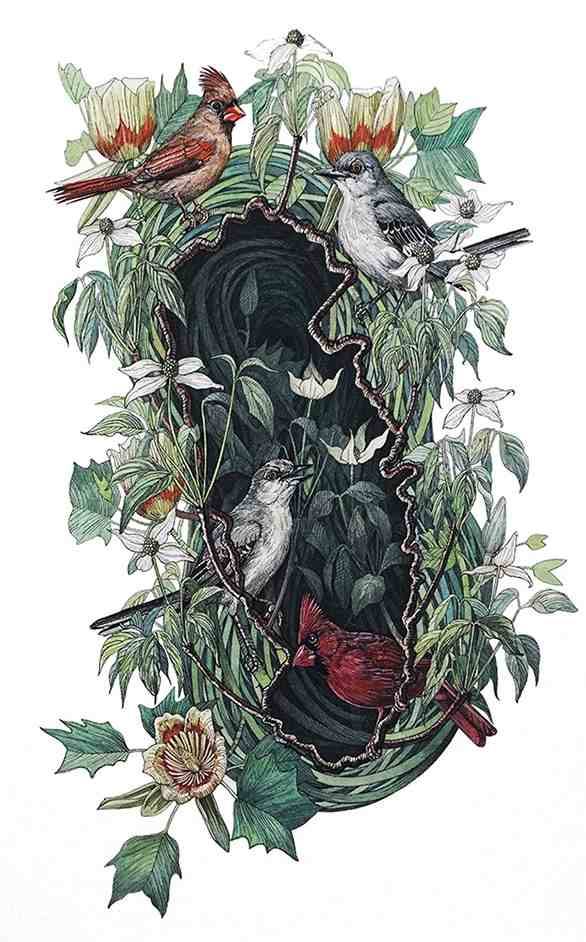

Original artwork by Bill Hosterman

Under a hot June sun, my family and I laid Dad’s wooden urn in an earthen bed and covered it with blankets of red dirt. Grandma used to tell Dad to put some of that dirt in his shoes when he’d ship off to wherever he was stationed overseas, so he’d always come home. Now he’d be “home” with her and the rest of the family, forevermore.

I hadn’t been back to Tennessee in decades, so it felt like divine intervention when Dad died just in time for me to take his ashes there on my way to my summer writing gig as Artist in Residence at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Dad’s death had been expected so long it became unexpected. He’d slowly faded into Alzheimer’s for eight years, and he’d lost his memories one by one until he, himself, became a memory: Mine. For years, I carried everything that Dad forgot in my own head. As Dad became starved of memories, I hoarded crusts and scraps of them. I tucked away every partial thought and broken phrase he shared, fearing that one day they’d be all I would have left to sustain me. But my hoarded memories didn’t sustain me. Laying him to rest left me weary, and the full weight of all that remembering toppled over on me.

I needed refuge, sanctuary, and a place to sift through my thoughts. I found that place in the Great Smoky Mountains. Almost immediately after driving into the park boundaries, my cell phone signal vanished and with it went some of my tension. I didn’t want to talk, especially not in the way you talk over a cell phone. Over the next few weeks, the silent woods listened to what I didn’t say. Tall trees kept a steady presence beside me as if to affirm, “I knew your Dad, too.” Some days, gentle brooks consoled me. Their familiar southern accents washed over my sharp edges and left them smooth as river rocks.

When I felt like my world was stopped, hiking kept me moving forward. When I felt like I’d lost my compass, climbing up to Clingman’s Dome and driving one-way around the Roaring Forks Motor Trail gave me direction. On the sun-dappled Sugarlands path, I let the midday light burn away some of the hoarded thoughts of my Dad, revealing green shoots of earlier memories from before he was sick. It was lovely to dig down to those examples of his true presence, personality, and essence, and see them grow.

While grieving, I began to discover cemeteries all around me. Maybe we see what we’re thinking about, but I found one graveyard behind my apartment, another at the edge of a parking lot, several outside white wooden churches, and more scattered in places off the beaten path. While plenty of the headstones belonged to adults, many others poked out of the ground like milk teeth. These belonged to babies that the Granny Women couldn’t save, and kids taken by accidents, typhoid, and influenza. Some were buried next to parents and siblings who had also died within days. The most common epitaph read, “Gone, but not forgotten.”

Gone, but not forgotten. My dad had been “gone” a long time before he died. I hadn’t forgotten him, but sometimes, he had forgotten me. The loneliest part of watching a loved one succumb to Alzheimer’s is realizing you’re becoming the only one who remembers some of the poignant moments that only the two of you shared. You worry that if you forget, your loved one will become both gone and forgotten. Some part of you fears that if this happens, a piece of yourself will be lost, too. If your father disappears, are you still a daughter? How do you keep a memory alive? How does its joy become an heirloom for generations to come?

The Great Smoky Mountains, became my searching ground for these answers. I studied others who’d held onto their identities as they mourned losses in the park. Some of these losses seemed far greater than mine. I learned about the Cherokee forced to leave the mountains on the Trail of Tears. I visited the houses of Cades Cove settlers who had to abandon their homes due to eminent domain so the Great Smoky Mountains National Park could be preserved for generations they would not live to meet.

I discovered that to stay connected to the past, you must memorialize it by sharing the brightest, strongest memories with someone young enough to remember them after you, too, are gone. In fact, many parts of the park are now designed to help younger generations learn about the everyday heroes of yesteryear. If you do seek human contact in the park, each place you visit is a memorial where people both grieve and celebrate those who came before. We remember Tsali’s bravery and selflessness as he sacrificed his own life so others in his tribe could live unharmed. We visit the Walker Sisters’ cabin and marvel at the independence and solidarity they showed as they refused to give their home to the park and lived without modern conveniences well into a modern age. We sit on Aunt Becky Cable’s porch and imagine the store she ran and how she took care of people so well she became an “Aunt” to even those who weren’t her kin. We respect her resourcefulness and grin about the wool socks she knitted to pay for her own casket. We think of these folks and find the brave, selfless, independent, loyal, and resourceful parts of ourselves, again. Because, on some level, the traits we recall from others live on in us. These traits are North Stars we give our children through our memories, too, if they want them.

The Smokies are a place where children are eager to sit on knees and around campfires and listen to stories about the past. These stories blaze trails connecting the past to the future.

One trail leads from the Little Greenbriar Schoolhouse, where park volunteer Robin Goddard helps preserve the memory of a sweet potato, orange as embers, warm in a child’s hands. Warm, all the way to school, and then bright at lunchtime, a sweet burst of sunshine in the starkness of winter. When modern kids hear her story and taste a sweet potato, it tastes as bright as that memory.

Another trail leads from the churches in Cades Cove where I heard memories of how, when someone died, church bells tolled once for every year of the deceased’s life. Everyone counted the tolls and could guess who had passed. Men rushed in from the fields. Women laid down their wash. Everyone pitched in to dig the grave and build the casket and prepare the body and console the family.

In those same churches, people sang hymns. They passed songs from generation to generation even if the parishioners couldn’t read. Everyone could learn “shape notes,” and sing tones that corresponded to different shapes.

Here today, I imagine the shape of grief. In my mind, it is round as the bottom of a church bell and just as hollow. What resonates out of that bell? Circles. Circles of life. One closes, another opens, and memories resound throughout the generations, bringing them into harmony.

How else could a monarch butterfly migrate through the Smokies the same way its ancestors did? How else could I end up sitting by a peaceful river, laughing with my little girl, the way my father once did with me? How else could I delight, the way he must have delighted, in the journey to becoming my daughter’s memory?

Someday, when my daughter is old enough to tell her grandchildren about me, a scientist will hike into the mountains, cut down a tree, and count its rings. The surrounding forest will be healthy and vibrant, but the tree’s rings will tell a story of a different time. One circle will bear a black scar from the 2016 wildfires that tore through Gatlinburg, Arrowmont, Chimney Tops, and many beloved areas of the park. Despite that scar, the scientist will observe that the tree grew on. It added more rings. More circles.

These fires have singed a ring on many family trees, too. They will be a blaze around which we tell stories for generations to come. We will remember those lost. We will remember how shopkeepers, emergency responders, ministers, neighbors, families, and strangers came together to grieve and rebuild with the same strength and goodwill toward others that the park’s ancestors showed, before. We will remember how we, too, became a part of the park’s history of overcoming grief as a community.

As long as these places and people are remembered, they will never be truly lost. Together, we must share our precious memories and keep the trails to yesteryear well-worn.

***

The original artwork accompanying this piece is by Bill Hosterman.

Bill Hosterman uses the process of a physical journey as the shape and theme of his drawing based work. His work is about the evolving relationship between the natural world and society. He has thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail, was awarded a Fulbright Grant to research art and culture in Southern Africa, and has participated in artists’ residencies in Wyoming, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He is an Associate Professor of Art at Grand Valley State University in Michigan.