“Some people skate to the puck, I skate to where the puck is going to be.” –Wayne Gretzky

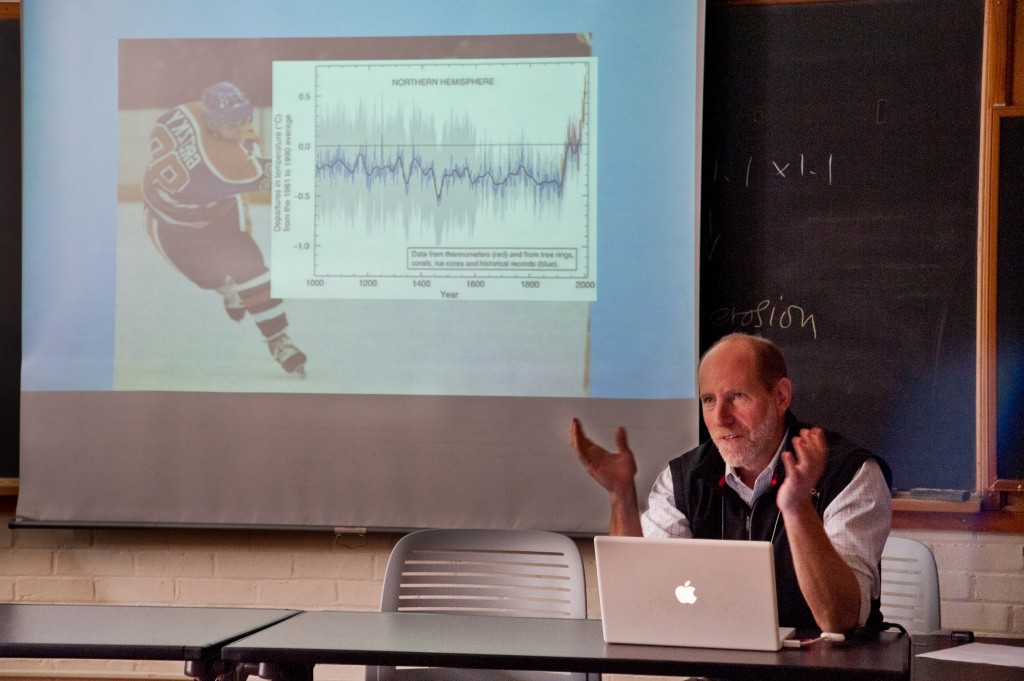

It seems fitting that Gary Tabor began yesterday morning’s panel on Sustainable Water and Land Conservation with this quote. Gretzky, as a former Canadian professional ice hockey player, is representative of the link between the United States and Canada that lies at the heart of this US/Canada Citizens Summit for Sustainable Development. But Gretzky’s philosophy can extend beyond hockey. Here at the Citizens’ Summit, we have coalesced around our collective frustration with the lack of progress since the original Earth Summit, as well as our collective optimism that, despite our track record, we will begin (and continue!) to create change for the better. It’s critical, however, to work in the right direction, to understand what the future may hold and to mold our action around that vision. If, as Gretzky would put it, we “skate to where the puck is going to be” rather than where it is now, the practices, policies, and priorities that we choose will gain greater traction in this continually shifting and developing world.

So how do we do this? How can we ensure that the solutions being developed and provided are the solutions that will work in ten, twenty, fifty years? Gary Tabor, who is Executive Director of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, urges us to break out of the “box.” The world doesn’t work that way, he says. It’s complex and messy, crossing borders and boundaries, blurring distinctions. We too often try to fit the world to our agenda, rather than doing the reverse. Take, for example, Yellowstone National Park. Created in 1872 as one of the original environmental “solutions,” the Park is a square, a “postage stamp.” “Is this really the way that ecology and sustainable conservation are managed?” Tabor asked. Animals don’t migrate in straight lines. Plants do not exist in a vacuum. “We have,” he says, “a two-dimensional sense of conservation—that it’s like a parcel. But really what we’re trying to do with these parcels is approximate the conservation process.”

An approximation cannot stand in for the real thing. This is a symptom of that initial Earth Summit’s failure; the urge to provide top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions that attempt to soften distinctions and round off hard edges. By painting with such broad strokes, we lacked the nuanced, attentive approach necessary to affect real outcomes. This is our task for Rio+20: to break out of the box, to skate to where the puck will be.

Caitlin Cromwell, Yale College ’14