Over the last half-century, scholars have spilled a lot of ink demonstrating the poverty of binaries such as nature/culture, wild/civilized, and country/city. However, despite the trenchant (and sometimes arcane) academic critiques, a good number of governmental and NGO organizations still consider a protected area, for example, to be one that doesn’t have people in it. Yet from the streets to the suits, from Andean South America to the Sierras and valleys of California, if you look hard enough, you can find encouraging examples that such critiques are finding their way out of the hallowed halls of academia and into actual practice. In Los Angeles, troops of “urban rangers” are teaching Angeleños that they inhabit the wilderness in their city; and a movement of L.A. “water makers” are trying to transform their metropolis into a new space of hydro-harvest and awareness. Meanwhile, in southern Ecuador a river has sued a government for damages to its natural integrity, and, to everyone’s surprise, “the river won.”

***

The Los Angeles Urban Rangers

Ideas of nature, historically, have been some of the most powerful, unquestioned, and taken for granted ideas that we have, and they have been very difficult to challenge,” said Jenny Price, a 1998 Yale History Ph.D., in an interview titled “Stop Saving the Planet!” this March on Stanford University’s Generation Anthropocene radio project. “Environmentalism in this country has long been rooted in this idea of nature as something that is out there. It’s a refuge. It’s not human. It’s the world that was here before us. The real world. The world that doesn’t change. It’s basically the place you go to assuage your anxieties about modern life.”

And this idea has been hugely problematic. The heart and soul of twentieth-century environmentalism, Price noted, was really “wilderness preservation.” “They said ‘Oh my god, we have to preserve these places,’ ‘We have to preserve this thing called nature.’” And, in turn, environmentalists “focused on how to preserve the nature ‘out there’ which has allowed us to ignore the nature that we actually inhabit ‘in here.’”

Ever the paradigm-smasher, Price’s answer was to turn to performance. She is also known as Ranger Jenny, part of an art collective called the Los Angeles Urban Rangers. “We are very serious about our ranger personas,” she said: “Tails tucked in. Always nice and neat.” She considers the LA Urban Rangers’ work to be akin to Jon Stewart’s – funny, performative, but with an utterly serious purpose. “We use the park ranger persona to engage issues in peoples’ everyday environment. So we take all that curiosity and wonder that people take out to Yosemite and Yellowstone about ‘Oh how does the world work?’ ‘What’s the geology?’ ‘What’s the natural history?’ and we take that into the places that people tend to take for granted and not ask questions about. So we take that to Hollywood Boulevard and Downtown Los Angeles and public access on the Malibu Beaches and things like that.” Like the shock-humor “culture jamming” tactics of artists in the alternative globalization movement, the LA Urban Rangers want people to ask old questions anew: “Where is nature? Where do you find nature in the cities? What do you want your communities to look like? What is the status of public space in Los Angeles?”

***

Remaking Water in Los Angeles, by Sayd Randle

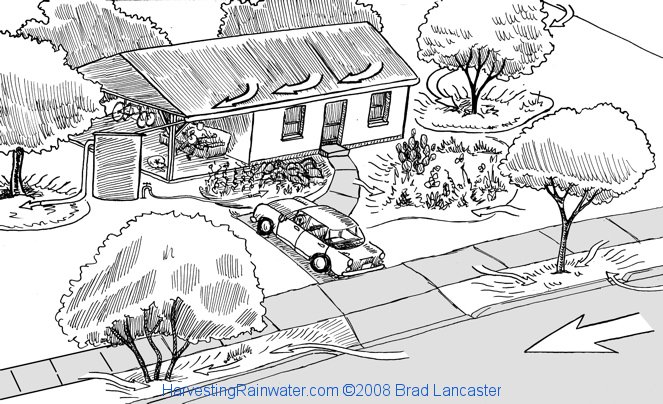

On page four of the second edition of Brad Lancaster’s Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond (2013), there’s a pair of images of the same single family home. Both are covered in arrows meant to suggest the directions that rain falling onto the property will flow. In the first drawing, of a relatively standard house surrounded by a lawn, everything is going out: off the roof, down the driveway, and into the gutter, joining the very big arrow representing the flows already in the street. In contrast, the second house sits on a lot with carefully cut bioswales, extensive vegetation, a roof gutter spout leading to a rain barrel, and curb cuts along the street. Here, the water arrows are redirecting to other spaces within the property, quenching trees and vegetable gardens. The street-water-arrow is less than half the size of the one in the image above it. In short: house number two is designed to harvest rainwater, house number one, to dump it off the property.

Based on the title of his book, it’s not difficult to guess which house Lancaster prefers. Less obvious from the relatively staid prose of his book is Lancaster’s propensity to break into almost-slam-poetry cadences (“I turn runoff into run-on, and I say, that’s right on!”), shout at his audience (“Rainwater should be treated… AS A WATER SOURCE!”), and wax poetic about the process of making humanure (exactly what it sounds like). All were on display in the standing-room-only talk he gave to 40-plus sweatyish adults and two kids selling homemade corn muffins and tea at the Los Angeles Eco-Village on June 26. For over two hours, Lancaster meandered his way through a PowerPoint loaded with photos of watershed decay and nascent regeneration, emphasizing ecological design principles and the hyper-local scale at every turn. When he concluded, the applause was long and loud, and a scrum of eager questioners quickly formed around him. The message of house number two had,apparently, struck a chord.

I reflected on this resonance as I waited in line to get my copy of the book signed, chatting with the other assorted groupies. There was the older man passing out his business cards asking if anyone knew of a site within the city where he could relocate his homestead/community space (his Silver Lake landlords were kicking him out in a few months), a twenty-something doing community outreach for a local eco-design/build company, a recycling activist, a guy waiting in line mostly to ask Brad what he knew about converting swimming pools. A sizable handful seemed to know each other from local community garden networks. The woman who sold me the shiny new copy of Brad’s book is the state’s leading home greywater activist. Lancaster preached well that evening, but he’d really just been stirring up the eco-choir.

Interestingly, the fire he seemed concerned with lighting among the faithful that night had nothing to do with policy, politics, or concerted opposition to any structural status quo. Design principles, home reworking, and neighborhood-scale organizing comprised the bulk of the talk. This surprised me, given how often other water activists cite Lancaster’s pivotal work towards breaking down legal hurdles to on-site greywater harvesting in Tucson. I brought up the political hole at the center of presentation as Lancaster scrawled a gracious inscription into my book, and he shrugged. This talk was about design and personal practice, getting people inspired, he told me. Including the political stuff would have made it too long and unfocused.

Weeks later, I sat at a picnic table drinking tap water from a three-gallon jug with David Kahn, the man from Lancaster’s talk who’d been hoping to save his urban homestead. Kahn worked for decades as a mainstream architect before a chance visit to a permaculture-inspired farm spurred a wholesale reevaluation of his life and principles. The homestead was the manifestation of his new priorities, designed “with nature” to serve, sustain, and educate the residents of his neighborhood. At some point, the conversation turned to the legality of the impressive operation we sat within – chickens and ducks and greywater and aquaponics and a cob oven and a composting toilet and at least a half-dozen other eco-hacks, most of which wouldn’t pass muster with any city property inspector. Patiently, he explained to me that this wasn’t an especially relevant or interesting conversation to his way of thinking. His work was to study his place, his community, figure out what was needed, and provide it. The laws and the city government didn’t particularly matter in this process. And so: not really worth his time to push hard at changing those standards and policies. His project was to produce a community parallel to, but better designed than, the mainstream. In a move I’d heard a few times in conversation about the environment in Los Angeles, he encouraged me to stop thinking in terms of the “artificial” maps of our political system. These arbitrary grids, after all, were just overlaid on the terrain of our real ecological community: the watershed. If we can see it and design with it, then the meaningful change will come, he implored.

Leaving the homestead that day, I walked 1.3 miles to the closest 704 Rapid Metro Bus stop. I prefer the 720 line, which is what I took home from the Eco-Village after Lancaster’s talk – it comes more frequently, magically seems to hit fewer lights. But it goes nowhere near Silver Lake, so the 704 would have to do. Shoveling handfuls of Trader Joe’s trail mix into my mouth while attempting to write up field notes, I recorded my dissatisfaction with the idea that the watershed map could be the only “real,” the only “true” one. The city’s transit map, after all, had a far more direct impact on my daily life. Tacky neon sunglasses shoved over my eyes to block out the mid-afternoon glare, I felt every inch the cranky heretic. Returning to my sublet apartment, I grimly noted that even house number one was far closer to a water sponge than the buildings in my neighborhood. Concrete and alleys, after all, absorb even less rainfall than lawn.

***

River vs. Government, by Chris Hebdon

If you traveled down Ecuador’s Vilcabamba-Quinara road five years ago, your car would have been jolting up and down on the dirt surface, jumbling over potholes and washed-out ruts. You would have had to proceed cautiously around blind turns fit only for a single vehicle at a time. Sensibly, most people rather preferred to ride horses or walk with pack-mules – safer, often cheaper, less bumpy. One local referred to the road as “a sternum buster.” The road also happens to be an increasingly important route for trucks hauling rocks from mining activities along the river further downstream. And so it made sense that, on the wave of a national infrastructure-building spree, the Vilcabamba-Quinara road would be paved and widened.

Yet “development” of that road would set off a local court battle that pitched riverine landowners against government environmental agencies and developers. Problems began when the Provincial Government of Loja carried out widening and paving of the road between 2008 and 2010. At the narrowest part of the canyon where the Vilcabamba River flows, which is known as the garganta or “throat” of the canyon, the road builders pushed hundreds of tons of rocks into the river, narrowing its breadth and speeding up its flow to the point where the river changed course downstream and, when a big rainstorm came, a large swath of farmland was washed out, including the farms of two immigrants from the United States, Norie Huddle and Richard Wheeler.

Huddle and Wheeler, who are husband and wife, decided to take a court case. But rather than taking a civil case against the regional government, for which they could have gotten money for damages if they won, they instead used a unique “Rights of Nature” provision in the national constitution to take the case “on behalf of” the Vilcabamba River. In Vilcabamba River v. Provincial Government of Loja, the judge found that the state had never conducted an environmental impact assessment, which is mandatory by law, and so in March 2011 the judge ruled on behalf of the river. It became the first case in Ecuadorian history where the Rights of Nature provision was successfully used.

Article 71 of the Ecuadorian Constitution of 2008 grants that “Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.” In this conception of Nature as Pacha Mama, natural persons are inseparable from human persons and all other forms of life. Thus harm done to the Vilcabamba River is understood as inseparable from damage to the human and other biotic communities linked to it. Judge Luis Sempértegui Valdivieso, who presided over the case, cited an excerpt of a speech given by the influential economist and politician Alberto Acosta, who helped write the constitution, explaining the spirit of Article 71:

Any legal system attached to common sense, that is sensitive to the environmental disasters that we know today, and that applies modern scientific knowledge – or, the ancient knowledge of indigenous cultures – about the way the universe works, will have to prohibit humans from bringing other species to extinction or destroying the functioning of natural ecosystems.

Acosta, in turn, quoted Aldo Leopold’s land ethic – “A thing is right when it preserves the integrity, stability and beauty of a biotic community. It is wrong when it does the contrary” – and from this advanced some fundamental premises of what he called the “Democracy of the Earth”:

a) Individual and collective human rights should be in harmony with the rights of other natural communities of the Earth;

b) Ecosystems have the right to exist and maintain their own vital processes;

c) The diversity of life expressed in Nature is a value in itself;

d) Ecosystems have value in themselves that are independent of their utility for human beings;

e) The establishment of a legal system in which those ecosystems and natural communities have unalienable rights to exist and prosper situates Nature in the highest level of value and importance.

Even though these ideas made it into Ecuador’s 2008 constitution, the devil, as always, is in the implementation, or social life, of the law. Which gets to the two caveats – the president can make exemptions to respecting the Rights of Nature if it is deemed in the national interest; and, even if a Rights of Nature case is won, it is the state who ultimately must enforce the ruling. Who will decide how nature is represented and whether it is in fact respected? The question is a thorny one, rife with contradictions. If the river had “suffered” from a landslide, for example, would this also qualify as an injury to its natural integrity worth remediation?

In a pathbreaking 1972 article titled “Should Trees Have Standing? – Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Christopher Stone argued that if Rights of Nature were ever to become a legal reality, they would be envisioned in the imagination before in the courts. “Each time there is a movement to confer rights onto some new ‘entity,’” Stone wrote, “the proposal is bound to sound odd or frightening or laughable.” There were times when it was unthinkable that people would articulate women’s rights, emancipation, civil rights, or, for that matter, the corporation as a fictional person. As the idea of Nature’s Rights goes from idea to action, it is crucial to attend to the question of who uses the law and who benefits.

In the Ecuadorian Amazon, for example, petroleum extraction continues apace and forms a gigantic part of state revenues used to build infrastructure and provide free schooling and health care. All of these are quite popular public services. The reliance of the state on petroleum and mining revenues has led to innovative proposals such as Yasuni-ITT, which would have seen the Ecuadorians paid by international donors to not exploit the oil buried underneath the Yasuni rainforest reserve. Unfortunately, Yasuni-ITT was called off after international donors only ponied up a fraction of the required funds. And in Vilcabamba, although the court ruling mandated the Provincial Government of Loja to rehabilitate the Vilcabamba River for harms caused, and although there are a couple roadsigns designating la garganta as a rehabilitation zone, the rocks have yet to be removed from the river.

In the meantime, Norie Huddle and Richard Wheeler have set up their own water-breaks along the river and tried to protect their land as much as possible from further floods. During this time, however, Norie Huddle was severely ill and hardly able to contemplate the lack of rehabilitation of the Vilcabamba River. Now recovered and getting back into the drift of things, she expressed both optimism and a sense of urgency. On the porch of her wood-and-adobe home along the banks of the Vilcabamba, she reflected on the one hundred years that it took to achieve the Civil Rights Act of 1964 after the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865. Certainly the idea of the Rights of Nature is a battlefield of interests, and often conflicting interests, she noted, but we need to encourage responsible living at larger scales. For that, she says, “we don’t have another hundred years.”

***

Coda

With all the talk in academic circles about how nature and culture are always interwoven, it’s sometimes easy to think that what’s done on paper is done in actuality. Often those putting the Humpty-Dumpty of nature and culture back together again are below the radar, working in social movements and on small projects that may go unnoticed. Sometimes they are called “political” or “activist” and too many of us turn a blind eye. Yet there are academics across the country who are taking these ideas from the suits to the streets. The legendary folk singer Utah Phillips put it aptly on Democracy Now! before his death in 2009, “If I look at the world from the top down, I get seriously depressed. The world is going to hell in a wheelbarrow. But if I walk out the door, turn all that off, and go with the people, whatever town I’m in, who are doing the real work down at the street level, like I say, there’s too many good people doing too many good things for me to let myself be pessimistic about that.”