Look at a satellite photo of the Earth at night. Some parts of the planet blaze with light, but much of the globe–home to more than a third of the world’s population–is still in the dark. Ainsley Lloyd reports from Ghana on the challenges a new generation of entrepreneurs are facing as they try to ensure energy access for all.

Emmanuel greets me with a wide smile and an outstretched hand, a six-inch-square solar panel propped on his corrugated iron roof just steps away from where we stand. Two months ago he received a visit from Energy in Common (EIC), an organization pioneering the use of tiny loans to fund clean energy for what the social enterprise movement calls the “bottom of the pyramid”—the 4 billion people living on less than $8 per day.

The EIC staff member who visited Emmanuel secured him a loan for 50 cedis, about $35, to pay for a household solar system. Now the panel on his roof feeds energy down one black wire through a window to an LED desk lamp. The lamp provides eight hours of light in the superblack Ghanaian night, and its phone charger attachment saves Emmanuel several ten-mile trips every week to the next electrified town. He’ll repay his loan in six monthly installments using the money that he no longer spends on kerosene. Or that’s the theory.

In practice, things get complicated. EIC is implementing a new model for financing and distributing solar home systems in which the organization matches thousands of individual borrowers like Emmanuel to thousands of individual lenders in the U.S. and elsewhere. These lenders aren’t the big donors that much of the philanthropic world works with. They are teachers, students, shop clerks and bank tellers, each one inspired by the idea that all it takes is a small loan to light lives. I was equally inspired when I heard about EIC, and I came to Ghana to collect data on outcomes among borrowers.

During my visit, Emmanuel was dressed in a white tunic and trousers of fancy eyelet fabric, which seemed an impractical choice given everything from the walls of his house to the floor underfoot was red dirt. He motioned to the old, gnarled shade tree next to the road on the edge of Dogoketewa village. Each village has a tree like this one, always with a long, wooden bench underneath, worn shiny smooth by constant use. As a visitor to their village, conducting surveys for EIC, I’m always offered a white or blue plastic patio chair. I want to picture rural Ghana with handmade everything. In truth, it’s handmade some-things, second-hand American clothing, and Chinese everything else.

We sit and talk through Kennedy, my translator.

At night, Kennedy tells me, Emmanuel’s children play in the light of the solar lamp. Sometimes his wife uses it for cooking. When the children study, they no longer suffer the smoke from their kerosene lamp. “He says it helps them a lot.”

It’s a dream come true for development. Other borrowers report that their children study up to six hours more each night. Though I appreciate everything EIC borrowers share with me, this discussion with Emmanuel is one of many encounters that leaves me feeling as though our interaction is rehearsed.

Hidden behind the script, though, is a story that no one was telling clearly. What happens on the lender side of energy loans?

***

Meeting Emmanuel uncovered the first of many complexities I’d find in Ghana’s Volta region, a long slice of former German Togoland separated from the rest of the country by the enormous Lake Volta. This 3,300 square mile reservoir filled in when the Akosombo dam was constructed in the 1960s.

In conversations with solar beneficiaries like Emmanuel I perceived an odd power dynamic between borrowers, who’d always like a little more, and inquiring outsiders like me, assumed to somehow control the purse strings. Predictably, this interaction makes it nearly impossible to get reliable data on the program benefits: the lamp is great! The charger is great! Six hours of extra study!

For most development organizations, the process is kept simple: deliver the products, assess the impacts, however reliably, move on and continue. It is perhaps easy to find a feel-good story about someone who got a solar lamp in Ghana, but that misses the details – details that provide EIC co-founder Hugh Whalan daily and ongoing difficulties.

To start with, EIC has to move solar systems like Emmanuel’s over vertebrae-crunching dirt roads for a full day to cover the 200 miles between the port at Tema, where goods are delivered, and Nkwanta, the district capital. It’s an expensive trip in fuel and time, not to mention the hassle that EIC goes through to find someone who will reliably deliver several thousand cedis worth of products to Nkwanta.

Once those products arrive, a loan officer must deliver them to individual borrowers. Payments are then collected every month for half a year. Our collection day with Emmanuel and five other borrowers in villages strung along the road between Nkwanta and Kpassa cost 7 cedis in fuel, and 10 cedis for my motorcycle driver. If we collected payments from all six borrowers we’d have had 60 cedis – more than enough for our expenses. But we caught only some of them at home, and fewer still had cash on hand.

In light of these challenges, Hugh has taken on the role of full-service professional with a durable commitment to long-term fulfillment. He and his staff handle logistical issues, visit borrowers for repairs when products break, and collect loan payments—all the while generating enough revenue to pay the bills and keep things moving. He has thousands of micro-lenders that have to be repaid, so he must budget carefully for the long run. That’s where I fit in. Hugh wants me to take a closer look at his energy-lending program. I’m a ground-truther, an auditor in a foreign land.

***

In May 2011, a month before I met Emmanuel, I had my first deep breath of Ghana’s damp, hot air from the runway of Accra’s Kotoka International Airport. While Accra showed me the puzzling, spontaneous order of full-tilt development, the Volta offered an undeveloped purlieu.

Most travel there occurs by motorbike, for reasons of both affordability and road quality. By the end of the summer, main roads can become impassable until government graders fill in their deep, rain-carved ruts. On either side, yams grow atop manmade mounds that stretch across the machete-cleared fields. In the mornings, my translator and I would ride past the sinewy, rubber-booted men who shaped these fields, all of them in their characteristic slow and steady gait headed to farm, water hauled in a salvaged five-gallon yellow plastic container. In this agricultural area, electricity from the Akosombo dam only reaches larger towns, where residents can enjoy endless light, television, refrigeration, and all of the other modern conveniences. Their more rural counterparts confine activity to daylight hours. They cook and read by the light of kerosene lamps and Chinese flashlights.

Ghana today is a collision of millennial globalization and 1940s America. As recently as 2005, 46% of Ghanaians lacked access to electricity through the national grid. But you’d never know it from the proliferation of cell phones. There are currently 63 mobile cellular subscriptions in Ghana per 100 people. By these numbers, cell phone use is more pervasive than electricity.

There’s no question, then, that Ghana is clawing its way towards first-world living standards, wishing for full access to electricity and eager to embrace technology that will make life easier. But the slow pace of large infrastructure projects like grid electrification frustrates these aspirations.

While the Akosombo dam just a hundred miles to the south pumps out electricity, the Volta region—like many others—lacks enough transmission lines and transformers to make electricity accessible in remote villages. High-voltage lines sometimes pass directly over the roofs of rural villages; all that’s missing are the transformers to bring that electricity down to a lower, useable voltage.

And because not everyone is willing to wait for the government to deliver on its promise of widespread electrification, social entrepreneurs step in.

In 2004, C. K. Prahalad touched off the social enterprise movement with his book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, pointing out to the world that more than half of earth’s people make less than $3,000 per year, but together represent a $13 trillion market. This sudden perception of overlooked opportunity has led a generation of young entrepreneurs to develop products and services that are both affordable and financially sustainable in the long run – in other words, that appeal to this massive and overlooked market.

Hugh Whalan, not yet thirty, is among them, and he’s determined to eliminate energy poverty.

Hugh co-founded Energy in Common in 2009 after realizing that larger efforts to fund projects for reducing carbon-dioxide emissions were failing to reach small-scale projects in Africa. In the fall of 2010 I had my first conversation with Hugh. He greeted me warmly, spoke with Australian accent and patience. Because I was just beginning to plan a summer research project with EIC, I had a long list of questions for him. He was happy to oblige.

First, he introduced me to the model.

Over the past decades, shiny black solar panels have appeared with increasing frequency atop the roofs of Ghanaian homes and businesses. It’s a convenient setup in a place with bright sun and inadequate electrical infrastructure. With this in mind, companies like Barefoot Power—one of Hugh’s suppliers—have begun packaging solar panels in self-contained energy systems sized for the individual home: a postcard-sized panel, a battery, a lamp and a cell phone charger.

Hugh’s contribution has been sorting the messy logistics of distribution.

He knew the rural poor were resourceful. From tiny in-home workshops, to food stalls in deconstructed shipping containers, they innovate and improvise, finding opportunities that larger businesses don’t perceive, can’t bother with, or aren’t agile enough to act upon. Unfortunately, the poor often abandon these opportunities because they don’t have capital and bank-based loans available on the scale that they need.

EIC helps to provide these microloans, which are used to fund the purchase of energy improvements—replacement of kerosene, for example, which can require upwards of 30 percent of family income for fuel. When borrowers no longer pour money into inferior energy, they can instead make monthly payments on a solar system and then enjoy the benefits for decades.

In May of 2011, immersed in research in the Volta, I learned early and quickly how complicated this process of improvement can be. Hugh arrived off a trans-Atlantic flight and immediately explained that we had a problem: The shipment of solar products that we had been counting on—a half container’s worth of 1.5 to 15 watt systems, enough to bring light to 6,000 families in rural villages—had been delayed in another port for several weeks.

What does this mean for borrowers? They started several months ago with a loan application. After waiting for their loans to be approved, they waited for funders—those average-Joe lenders across the ocean—to select them from EIC’s lending website. After this new shipment delay, borrowers in Nkwanta had waited almost six months for their products to arrive. By the time of delivery, many borrowers will have lost trust and interest in the organization.

Over the coming years, economies of scale will solve many of these start-up problems. Growth in demand will make it feasible to order a full shipping container of solar systems; Hugh won’t have to wait for the other half-container with someone else’s goods to be offloaded elsewhere. Once the systems arrive at port, expanding demand will make the trip to Nkwanta less expensive too, since hiring someone to haul one big load to Nkwanta costs less and consumes fewer resources than hauling many small loads.

When the systems are delivered and payment collection begins, economies of scale will continue to improve the EIC model. If it costs fifteen cedis to visit a village to collect ten-cedi payments, it makes far more sense to do this if there are ten borrowers in the village rather than one. Denser demand spreads fixed program costs across more borrowers, making the whole program more financially sustainable.

Then there’s the feedback effect. Cheaper borrower visits mean more frequent borrower visits, faster repairs on systems that break, better borrower education, and a great deal more trust from the borrowers – trust in both EIC and its technology. All of this, the positive reinforcement, sparks more interest in solar among community members.

Economies of scale, then, will make Hugh’s job easier. So might better infrastructure and international efforts to support economic development in Ghana. But people—not policy—will ultimately solve energy poverty, however slow the process and however rough the road.

***

Emmanuel was wearing yellow foam slip-on sandals when we met. “Akwaaba” (Welcome) he nodded.

“Ya eja,” I replied.

Kennedy, like Emmanuel, spoke quietly but warmly when he translated. He introduced himself with only a first name.

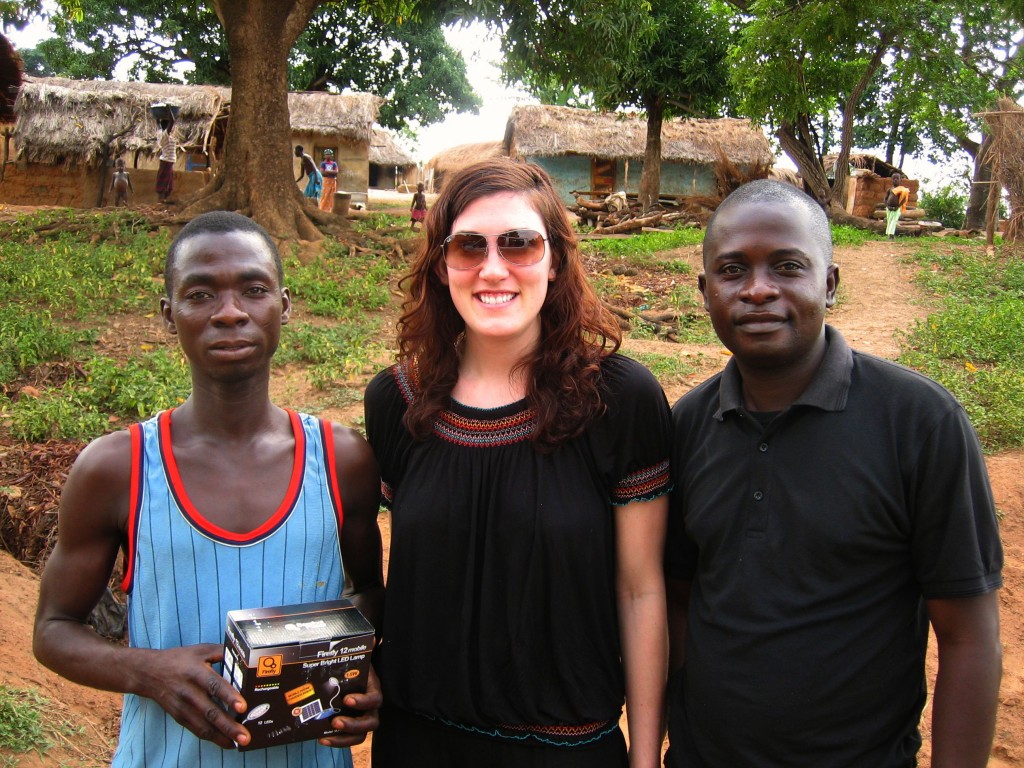

“He wants you to take his picture,” said Kennedy. “He says you will show it when you go to America.”

“Okay.” I snapped a photo of Emmanuel as he sat solemnly in his plastic patio chair, bright blue lamp in hand. He didn’t smile for the photo, but after meeting dozens of villagers I’d learned that few Ghanaians do. I showed Emmanuel the photo and he finally grinned. I nodded back, and began the somewhat convoluted communication chain with a turn to Kennedy. “How does he use his solar lamp?” I asked.

Emmanuel’s name, though it is a name that I encountered frequently, has been changed from its original to comply with Internal Review Board rules on research involving human subjects.