“Why do you want to protect the elephants?”

A friend of mine asked me this on Weibo after the death of Bonsai, a 26-year-old mother elephant who was shot on my seventh day in the Samburu National Reserve in Northern Kenya.

My friend is a Chinese conservationist who has for years strived to protect the wildlife in his hometown. He understands the intrinsic and environmental values of elephants. He also knows something about the economic benefit and the cultural significance of elephants to the local Samburu people. His question was not a simple, general criticism. He was asking me to confront my own motivations for coming to Kenya.

Social scientists believe that every individual, consciously or unconsciously, tries to find meaning in his or her life by seeking values – the things and events that people desire, aim at, wish for, or demand.

The local Samburu people support protecting elephants, because in their traditional culture they regard the majestic creatures as members of their community. Thus it is morally right for them to protect the species. But another reason is perhaps more pressing: local people have come to realize elephant tourism creates employment and generates income for the community. Still, not all members in the community perceive that they are benefiting or benefiting enough from the tourism. Poaching by locals and outsiders is a major problem. For some, elephants are merely walking money. Ivory smugglers take risks in order to make profit. Some of the offenders are actually unfortunate people who fell upon desperate times. They are simply seeking to support their families, provide better opportunities to their children, and ultimately win affection and respect from their own community.

The problem of international ivory trade, as I see it, is fundamentally the conflict of people’s different values. Many individuals, organizations, governments, and others are directly or indirectly involved. They hold very diverse and maybe competing views with respect to “how we are going to use the natural resource and who gets to decide.” The wide sets of values and interests lead to a variety of problem definitions which reflect in the different goals desired, situation descried, causes identified, and solutions proposed. As is suggested by a content analysis of Chinese and English online discourse I conducted last year, Chinese and western societies are divided on their understanding about the scale and scope of ivory black market in China, the major ivory consumers, and people’s reasons for buying ivory.

Similar to many of my Chinese compatriots, I have a lot of questions about the “facts”. The clandestine nature of poaching and illegal ivory trade make it difficult to obtain authentic data about the problem. But perhaps what people think are the facts is more important than the facts. The call for more data alone cannot resolve uncertainties, because many of the uncertainties are in actuality the conflicting values ingrained in different participants.

So why have I, a Chinese conservationist, come to Samburu to witness the death of an elephant called Bonsai.

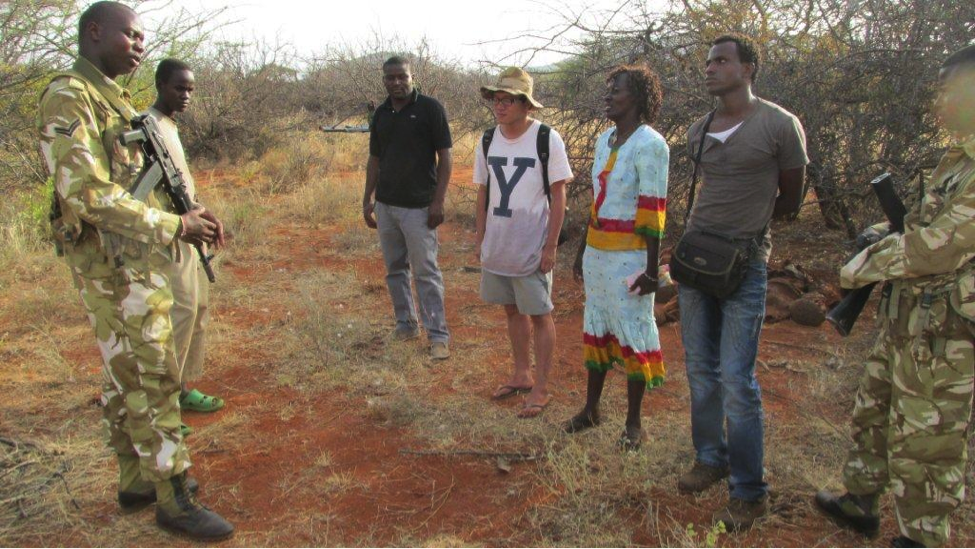

As a Chinese national bilingual in English and Mandarin, I am able to see the different cultural outlooks relevant to the issue of elephant conservation. By talking to conservationists, authorities, and citizens in Kenya and China, I want people on both supply and demand sides to share with me their insights and help me understand their concerns. In this way, I am attempting to help all participants achieve a more comprehensive and contextual understanding of the problem. I hope I can help clarify the common interests. And I hope I can help facilitate the search for solutions that are logically rational, politically feasible, and morally justified. Understandably, I also hope this project can help me build network, foster relationships, and create opportunities for my future career. But my dear friend, I can also say the primary reason that motivated me to take this project on: I wanted to come to Africa! You know how I love travelling!