SAGE Magazine is honored to award Sierra Dickey’s “The Live of Plovers” honorable mention in our 2014 Emerging Environmental Writers Contest.

Curious creatures inhabit a place of such dynamism. One of them is the piping plover, an ethereal shorebird. The plover is the angel of our place. She is white and small, and dances lithely. She is also a messenger. But unlike the cherubs of God, who are vessels, the plover embodies truth-in-motion. Her form and her nature make laws for these hinterlands that are too easily broken.

I once thought of Cape Cod as the X-Men character of landmasses, one with unexpected and preternatural powers that would be envied world-round. But this was only my young imagination — anxiously stimulated in the era of Katrina and the Indonesian Tsunami — fortifying a defensive moat around my home. I assumed we were water-repellant, and my dreams made sand strong against oceanic threats.

Recently I have been able to reteach myself about our sediment situation. It turns out that Cape Cod isn’t a burly pile of wet sand, but a delicate swipe of sediment. Although flooding is not a threat, erosion is. Erosion is our blessing and our curse. This place is like a starlet with endless costume changes, massaged every year by the ocean into a new form. This place is also like a starlet in its vulnerability: so public, so beloved, and so easily shaken. Without the right protections we might spiral out of control, or melt out of existence.

An honest two-hour drive from Boston, the outer Cape remains (for all practical purposes) pinned tight to the Eastern Seaboard. And yet our station feels removed. The arch of this isthmus swoops precariously away from North America, and reaches for Atlantic isolation. Out here in the ocean, we fall under endless casts of the “painters light”. The artists and the poets come here for the atmosphere of shades.

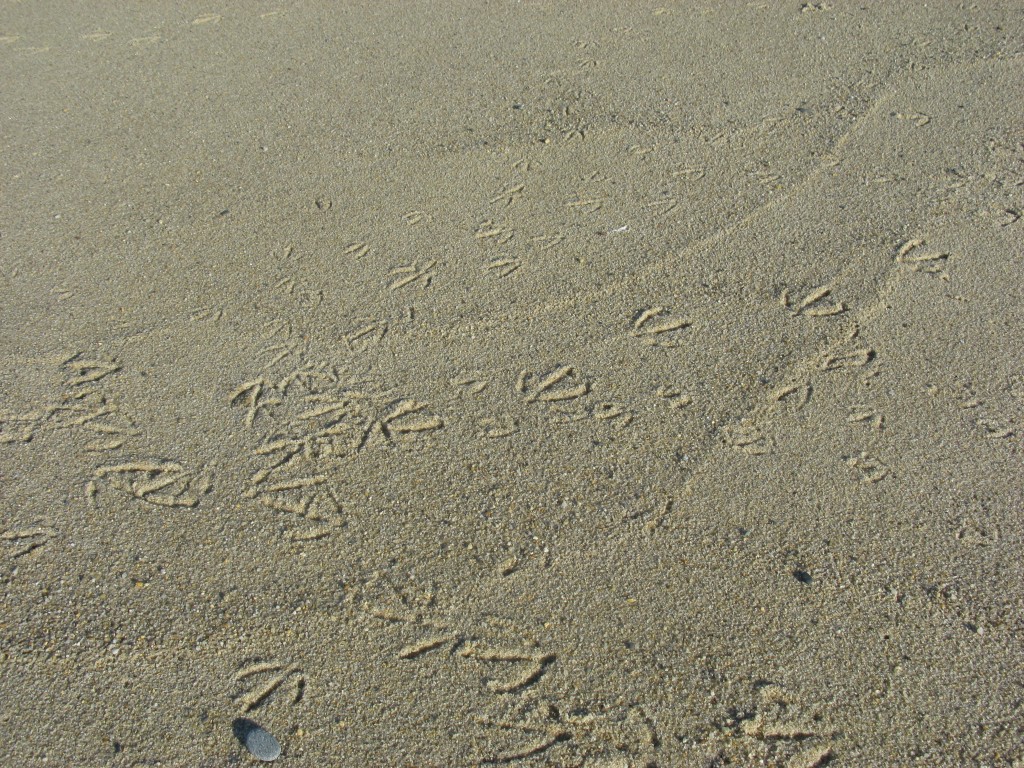

The piping plover, our bird of place, is also known for its fragility. A hoppy little thing, it has a plump white body, and long, spindly yellow legs that move like the cartoon Roadrunner. It’s a shorebird – the rarest breeding in North America — so its wings function as flyers, moving back and forth between the Gulf and the Northeast every year. And yet those wings tuck back so neatly and tightly onto the bird’s torso that you don’t easily notice them. When you catch a glimpse of plovers, zipping like pinballs up and back from the break to the high tide mark, they look less like birds and more like magical bugs or white rodents. I think their triangular bird feet were built as a bonus, just for levitation. The marching lines of footprints they leave on the shore look like the effacing petroglyphs of ancient paths. They barely leave tracks on the wet sand; instead, just etchings.

Plovers are endemic to our outer-lands. They make their habitat on barrier beaches–homesteading slow quicksand. We get them up on Cape Cod and others get them down along the Gulf of Mexico. Their petiteness is not the only thing that makes them fragile; piping plovers are naturally vulnerable, even prostrating birds. In this unselfconscious insecurity, they are just like our landmass.

In 2010, conservationists and citizen ornithologists — the people who worry most about the plovers — had their concerns confirmed by national news: the birds’ southern winter hideaways would be the first to get sloshed with oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Being small, flighty, and not entirely photogenic, these birds were not scooped up and scrubbed clean by the people in orange gloves. At least I didn’t see them next to the shit-brown pelicans in any of the Dial soap commercials. Thus, the already threatened plovers became even more vulnerable. The Audubon Society and the National Seashore started to whir their conservation gears. The birds that made it back up to the Outer Cape deserved safe harbor. In order to ensure this, they had to amp up defenses, and so the war for habitat ratcheted up a notch.

The plovers and the people of the Outer Cape are vying for space in a very particular environment. Out here is where land use bottlenecks. Down near Duxbury, where the Cape’s arm flattens into the shoulder of Massachusetts, there is more beach and road for everyone, but less so for the towns up on the skinny wrist.

I have been spared from seeing anyone spear a plover onto a clambake kebab because thankfully this war crops up more in township rhetoric than anywhere on the beaches. Newspapers and town-hall meetings aside, bumper stickers provide the most interesting public forum. The banner representing pickups, Humvees, and Expeditions reads: “PLOVER TASTES LIKE CHICKEN!” The one representing Subarus and rusty two-seater Saabs: “SAVE THE PLOVER!” These two statements challenge each other in passing on Route Six or when jammed-up in close quarters on Commercial Street at four in the afternoon.

On the physical side of conflict, the beach is quite an ironic battlefield. There are nests in the trenches. In reality, these are just tire tracks in the sand; fat rivets that invite shorebirds to inhabit. Unlike footprints, these indentations made by cars don’t shimmy away in a day, but stay packed down. Hollows in the sand, they provide small straight angles for plovers to dig and rub and peck straw into. Best of all, when a mama plover sits in her nest, built within a tire track, you can’t see her. Neither can unleashed golden retrievers or the balding gulls. A plover can bury her little head when she wants to check out the scene. She inches to the left: twitch, twitch, twitch. And to the right: twitch, twitch. Crouch and scoop, back down below horizon line.

Thanks to the unexpectedly fervent presence of the Seashore and the Society, the plovers aren’t losing this war, and they aren’t winning it either. They get nothing but bad press, but they are making strides. All the beach closures prove it. All the closed beaches are why the people are so mad.

The Seashore and the Audubon monitor the outer beaches year-round. The government-issued signs with diagrams about the specialness of the plover stay up during all months. For most of the fall, there are skimpy plastic wire and wooden pole barricades erected around the nesting habitat. The plastic looks like it’s made out of the same stuff that brace-faced tweenaged girls wear around their wrists, and the poles wave around in the wind, sticking out of the sand at slanted angles. These are the casual, off-season defenses. Besides, far fewer people drive on the beach in the off-months. And the dove-haired ladies who walk dogs cling-wrapped in windbreakers wouldn’t dare let Spot get a bite of birdy.

In the spring and summer, things start to amp up. Instead of wistful wiring and limp chopstick poles, the monitors bring out the big guns. Neon orange plastic netting gets stretched between real plywood stakes. Extra “WARNING: Endangered Species Habitat” signs go up, laminated twice over and nailed onto the wood. Kids too young to sport full mustaches don the taupe-and-green canvas uniforms of the Seashore and appear everywhere with clipboards. They trudge through the sand and scribble things down, squinting and sweating in the June sun. Their broad brown hats don’t do much to protect them.

Off-Road-Vehicles. The darling of the motorheads.

If there was a mechanical ocean constituted by car parts, greased gears, and metal crab arms like the ones wielded by aliens in District 9, the sound of those waves crashing would be the sound of an oncoming ORV.

ORV “enthusiasts” as they are termed, take their SUVs, Dune Buggy Jeeps, and sometimes their four wheelers, out onto the outer beaches. Those that go in SUVs bring tents, grills, fishing poles, and large speakers. They move-in to the beach, tailgating daringly close to the breakwater. People on four wheelers and in buggies don’t go out and stay, they just charge out on joy rides, fresh from a boozy P-Town oyster bar. Accelerators tease the slippage area along the dunes and roar through the flats at low tide.

The National Seashore charges a high price for off-road permits, like they do for fire pits and non-residential beach stickers. So these enthusiasts are re-creators but certainly not casual ones. They pay up and plan ahead for their chance to unleash their engines on the sand. But releasing giddy petrol-power on the sand also means unleashing doom upon the nesting plover.

In high summer when the beaches are sporadically closed to ORVs, these folks feel cheated. Another uncomfortable effect of seasonal land use bottleneck: the birds and the drivers and the locals and the out-of-towners all want the sand at the same time. It’s troubling to decide who “deserves” the beach.

After 2010, the Seashore started closing beaches entirely and no one — and no thing — was allowed access. In reality, full-blown beach closures have occurred since 1986 whenever many flocks of plovers end up nesting in close proximity on one beach. In 2010, however, the Seashore started closing the same beaches repeatedly. They hoped that giving the plovers back their uninterrupted habitat for a few days a week would ensure that a few couples nested successfully. They imagined they were stabilizing the population that had suffered such losses in the Gulf; they would close and block off a different beach for three to four days each week, and all of a sudden the birds would have their habitat back. But in the human realm, no one got a price-deduction on permits or parking stickers. The enthusiasts became the enraged. If you’re pro-vehicle you aren’t enthused about the little lives that roll away in the wakes of your displaced sands. Hard metal and stench, gas and gears have already got you going. I believe these people need a reorientation of the senses. Getting acquainted with the plover might just slice open the suture binding them to mechanical mentalities. I believe this bird can teach us how to move.

The shore is silent. The sun is a tuning fork: reeds, wind, and wave make one clarifying hum. The sand is warm, magnetically warm. It calls to you like your unmade bed does in those first five minutes after waking.

Everything is moving slightly. You dig your foot into the sand and it rolls away, luxurious. When the wind makes off with the sand on an upswing breeze it titters away, seeming less like particulate and more like a strip of silk. The waves move like molasses. Slow bass drums.

Down by the water’s edge, cottonballs whiz around, moving in call-and-response with the petite bayside waves. No, not cottonballs: birds. Plovers, doing their running dance, buffering the break. The sensuality of slight.

Artists come to Cape Cod to work, and sometimes to live. The light and the daring feeling they get from living on a precipice heighten their receptivity. The blue out here is bluer. As Stanley Kunitz say, the “brine-spiked” air is what we’re snorting.

“Oh, to love what is lovely, and will not last!

What a task

to ask

of anything or anyone,

yet it is ours,

and not by the century or the year,

but by the hours.”

Mary Oliver, who lives in Provincetown, wrote that in her poem “Snow Geese.” She writes things like that in many of her poems. The Cape, our common teacher, instructs us about impermanence. There is a lot of Eastern religious philosophy in Oliver’s poetry, but there’s a reason she came to the Outer Cape to practice. This land is an existent reminder of Buddha’s dharma: detach yourself and find presence in passing.

If we want to be visceral Cape Codders we ought to locate ourselves in this state of passing. I know that we cannot fully understand where we are unless we internalize a piece of our surroundings. In June you will find me lying on the sand, a piece of straw in my teeth. I will draw in the sun that perforates my cells and run to greet the Gulf Stream as it comes to carry us away. I will prostrate myself in the style of the plover.

So, Cape Cod is special for artists and ORV enthusiasts. By this logic, is the National Seashore nothing more than a welcome mat?

Activities like off-roading and tailgating are ontologically opposed to life on the Outer Cape. But the life of receptivity, of sensual fragility is for more than just the artist contingent.

I know that the ORV cadres revere the outer beaches. When I think about them I imagine a man, employed by the seasonal economy. After 40 hours a week slinging shellfish on the fryers, or manning the bar at The Beachcomber, he takes to the shore to slip off the hinges. He and his get their kicks from the shore just like I do. There is some element out there they also need. But perhaps they don’t revere this place enough. I want them to practice reverence differently. Off-road vehicles exacerbate erosion. Our swipe of sediment, hanging just so before the onslaught of the Atlantic can’t accommodate everyone’s idea of fun.

In order to love and live with what can’t last, we need to get oriented with vulnerability, and we need to move with gentleness. When you walk down those old and greening wooden stairs, don’t slam your heels. Let’s take that atmospheric injection from the Outer Cape entirely into our bloodstream. Our endemic species, the umbrella bird, can be our choreographer. Levitate, oscillate, and twitch. Do not rev.