The year 2013 opened with a horrifying series of photographs depicting the vast scope of the shark fin industry. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of shark fins decorated the rooftops of Hong Kong, drying in the hot sun. The harvest is driven by the market for shark fin soup, a status symbol and delicacy in Chinese culture; and, although the Hong Kong government has taken steps toward reducing demand for the soup, shark fisheries remain a highly profitable and grossly under-regulated endeavor.

The insanely high prices that shark fins bring fishermen have long been an obstacle to conservation. According to economists Quentin Fong and James Anderson, the average price for a ten-inch shark fin was $415 in 1998 ($586.15 in 2013 dollars). When that kind of money is on the table, it can be understandably difficult to convince fishermen to become conservationists. And the results of these hefty prices have been catastrophic: tens of millions of sharks are killed for their fins every year.

This depletion poses a problem for more than just sharks. As apex predators, sharks govern marine ecosystems by keeping populations of mid-level predators — fish like snapper, grouper, and mackerel — under control. If left unchecked, these fish may decimate prey populations, potentially causing the collapse of entire ecosystems. Sharks are slow-growing creatures that give birth to few offspring, characteristics that make their populations susceptible to overfishing — a problem that shark finning has brought to harsh light.

Consequently, shark-finning has long regarded as synonymous with unsustainability. Yet, crazy as it sounds, there may be a way to reconcile shark fin harvesting with sustainable fisheries management.

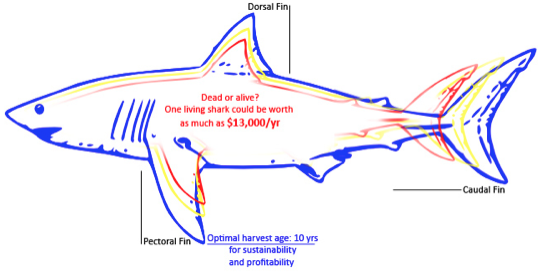

In 2002, Fong and Anderson estimated the optimal harvest size and age of blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) that would maximize their economic value. The study not only included typical biological factors such as growth and mortality rates, it also considered the quality of the shark meat, an important factor in market value. (Sharks typically ‘produce’ three types of fins — dorsal, pectoral, and caudal — which grow to different sizes and fetch different prices.)

Fong’s and Anderson’s model suggests that the optimal harvest age of a blacktip shark occurs after the shark has reached sexual maturity — and thus had a chance to breed. (Male blacktip sharks mature at 5.25 years and females at 7.25 years; the model recommends an optimal harvest of 10 years.) Fishermen would be better served by allowing sharks to mature and reproduce before being harvested, both ensuring the survival of shark population and maximizing their own profits by catching sharks with large fins.

That certainly sounds good. But is a one-time bowl of soup really the most rational way of using these spectacular creatures? Or is it possible to extract recurring value from a shark — to reap its benefits over and over, rather than just cashing in once on its flesh?

The answer to this question might lie with the shark diving industry. SCUBA aficionados worldwide pay premium prices to dive, sometimes with the protection of a cage, with large sharks such as tigers and great whites. Even gentler sharks, from hammerheads to whale sharks, attract divers to remote destinations such as the Galapagos.

Recently, two scientists, Austin Gallagher and Neil Hammerschlag, undertook the task of analyzing the global “distribution, frequency, and economic value of shark ecotourism.” The study identifies 376 tour operations across 83 locations and eight separate geographic regions, illustrating the impressive scope of the industry; shark tourism in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and Oceana is especially vibrant. While the shark fin industry primarily targets Chinese consumers, the shark tourism industry attracts naturalists, snorkelers, scuba divers, and photographers from all over the world.

It’s extraordinary just how valuable these animals can be. A single grey reef shark in the Maldives has an estimated value of $3,300, far higher than any fin. Another study suggests that a single shark is worth $13,000 a year, and has a life expectancy of up to 15 years. No wonder the Bahamas, which has become a popular destination for shark divers, rakes in annual revenue of $78 million through shark interactions with visitors. What’s more, these industry values don’t include the spillover benefits to associated tourism industries, like lodging and restaurants.

Demand for shark fin soup isn’t going away anytime soon — but what costs are shark fin consumers inflicting on society? If a living shark is worth more than a dead shark, perhaps the already astronomical prices of shark fins should be raised even higher to reflect the true ecological and economic benefits of living sharks. Policymakers need to realize the immense opportunity presented by shark diving and snorkeling and implement better protection measures for these misunderstood predators.

To start, the shark fishery needs to be recognized as a large-scale industry with global consequences — and as such, it needs international management and monitoring, starting with expanding the protection of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species to cover targeted sharks such as porbeagles and hammerheads.

Considering that much of the industry remains protected by the veil of the black market, implementing regulations and increasing taxes on the sale or importation of shark fins won’t be enough. Policymakers need to work with local communities to develop economic incentives to better manage their shark stocks, such as diversifying through other industries, such as shark diving.

To address both the horror of cutting off sharks’ fins and throwing the still-living animals into the ocean, and to better monitor the catch numbers of different species, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and other organizations are pushing to require that all sharks be landed with their fins still attached. In turn, this would generate species-specific landing data, which would enhance the effectiveness of fisheries management strategies such as Total Allowable Catch (TAC).

In turn, designating a TAC for each shark species in each region could serve as the basis for an individual tradable quota (ITQ) system. This would reduce the need to “race to fish” or over-capitalize on fishing equipment. It would also reinforce landing sharks with their fins attached, as fishermen would not be able to simply cut off and store as many fins as possible on their boat. Each fisherman would be given a permit to harvest a certain number of sharks throughout the season, which could then be bought and sold amongst fishermen depending on their preferences and harvest costs.

Yet even limiting Total Allowable Catch is not enough, as other human activities, like bycatch and habitat loss, present threats to sharks. Therefore, protected areas and no-take zones should also be implemented as part of any shark fisheries management strategy. Community members should be educated on the ecological importance of sharks and included in the decision-making process. Designating shark sanctuaries, or marine protected areas, that are enforced and monitored by community members would allow these communities to “own” their stake in the health of the ecosystem. It would also diversify their local economy, reducing risk from over-reliance on one or two key fisheries.

These policy proposals are only the beginning of a comprehensive shark conservation strategy. The overfishing of sharks has been overlooked for too long, and it’s going to take international cooperation to restore population levels. Through community-based initiatives, education, economic incentives, and better monitoring and enforcement of the shark fin fishery, we might just be able to achieve sustainable management of our global shark populations — and relegate photographs of shark fins on Hong Kong rooftops to the dustbin of history.