Roads in the United States see over 51 billion pieces of litter each year, which works out to about 6,729 items per mile. Cleaning up that litter costs the United States government upwards of $10 billion each year – and that’s only in the U.S. Litter is a world-wide problem, and while many are shocked at seeing turtles suffocating on a plastic bag, many view litter as just those soda bottles, cigarette butts, and wrappers that hit the street and eventually disappear—whether they biodegrade or someone else picks them up. In the ocean alone, hundreds of thousands of sea turtles, whales and other marine mammals and more than a million seabirds die each year from ocean pollution and ingestion or entanglement in marine debris. On land, litter can cause chemical contamination, soil damage, and can negatively affect wildlife health. But could the 21st century solution to litter be found on our smartphones?

A year ago, if you had asked Jeff Kirschner whether he was an environmentalist, he probably would have said no; or, at least, no more than any of the other yippies living in the Bay area. A writer with a career in advertising, Kirschner stumbled upon the idea of a virtual landfill eight months ago, in the form of a plastic tub of kitty litter. As he was walking with his two children through park, his 4-year-old daughter, Tali, suddenly pointed to a box of trashed kitty litter. “Daaaaddy,” she exclaimed, “that doesn’t go there!” Kirschner was taken aback. He, like many adults, had become so desensitized to the idea of trash in the natural world that he hadn’t given it a second look. It took his 4-year-old daughter to remind him of the massive problem our planet faces.

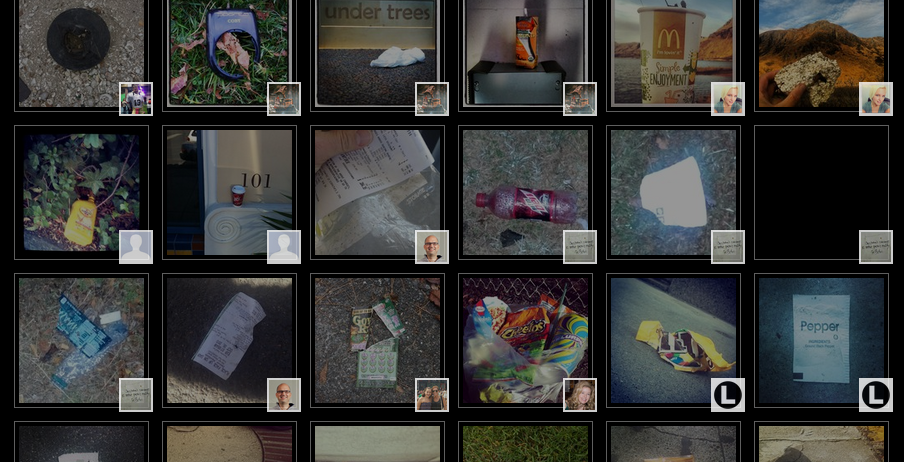

This was when Kirschner started Litterati with the overarching vision of a litter-free planet. The idea of Litterati is simple: individuals see trash, snap a photo and post it on Instagram. Once they capture the image (often in an artistic or beautiful way), they throw away, recycle, or compost the Styrofoam cup, bottle, or banana peel.

Kirschner hopes to bring the power of social media to bear on a problem with the potential for tangible results. Now that enough people have caught on, Kirschner has started to see some trends. He’s able to map where litter is piling up so that something as simple as trashcan placement or as complex as environmental education can be restructured on a city-wide level.

There’s also an opportunity for companies to become invested in where their products end up. While Kirschner isn’t trying to blame, say, Starbucks or Marlboro for coffee cups and cigarette butts all over the street, he does think that there’s a big public relations opportunity for them to incentivize and reward customers. “Can you imagine if Starbucks told their customers that for every 10 pickups of litter, they would receive a free cup of coffee?” Kirschner went on to explain how he loves the idea of being able to turn the action of picking up a piece of litter into a reward. Suddenly, everyone’s participating for that free cup of coffee. But Kirschner is also looking long-term. “If you had a kid, and you’re like, ‘Okay, take out the trash and I’ll pay you $5 every week, two things will happen: your kid counts on that $5 every week, and pretty soon, $5 won’t be enough,” Kirschner explained. While it can be fun for companies to get involved, but his first priority is making people feel good about cleaning up our planet. Kirschner doesn’t believe that Litterati should use its platform to antagonize or punish a particular company.

Beyond the warm and fuzzy feeling one gets from cleaning up the planet, Kirschner stresses the differences between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Imagine picking up a fallen Heineken bottle in New York City. It’s an isolated action, and hopefully you feel an intrinsic reward for what I’ve just done. But suddenly that moment becomes more interesting when you turn picking up a Heineken bottle into a photo opportunity or creative expression. Even more powerful, Kirschner says, would be visiting the Litterati website later to see how many other people in Germany or Ghana have picked up Heineken bottles, and how they chose to capture their experience.

Kirschner has big plans for his nascent project. When he first had the idea, he decided to use the smartphone app Instagram, since so many people were already using it on a daily basis. In the future, he’d like to have his own Litterati app. The app would include automatic geotags (to locate the litter on a world map), monthly reports of the amount of litter removed from streets, and, ideally, some of the same photo capabilities that Instagram has perfected.

Litterati has the potential to let people understand the impact that they, personally, are having. Anyone could say, “I picked up 150 items in the month of January.” Beyond that, they would be able to separate out type of litter or brand. Eventually, there could be connection with other people when you’re able to see how many pieces of trash your friends have picked up along the way. That’s a way to start incentivizing and rewarding. Kirschner is ambitious but realistic about these possibilities. “[The litter problem is] potentially insurmountable, but we’re going to start right here and right now.”

Litterati is a highly visible solution to a highly visible pattern. Litter is everywhere you walk. It has infiltrated both our natural world and our built environment so much so that many of us don’t even notice it anymore. “Maybe there’s an opportunity to create this fun, engaging, informational data experience that helps us see our litter in a different way,” Kirschner says. “Individually, you can make a difference. Together, we can create an impact.”

So far, 21,097 pieces of litter (and counting) have been photographed, catalogued, and (hopefully) properly discarded. As this number continues to grow, Kirschner doesn’t know how far Litterati will go. “It’s just organically happening, but the biggest challenge will continue to be awareness.” But Kirschner isn’t too concerned with Litterati’s overall impact: he knows at least two children, his son and daughter, will never litter. “If that’s the only legacy of Litterati,” Kirschner says, “I’m very satisfied with that result.”