Moody spent two hours scouting Namenalala’s 107 acres. He found steep hills, rocky shores, and a complete absence of freshwater. In short, there were reasons why people had left this place alone. Moody got back on the boat but Moody peered over the edge at the coral reefs down below as the driver started toward town. “Can we just stop here for a few minutes?” he asked. He affixed his snorkeling mask over his narrow hazel eyes and flopped over the side. With a big breath he dove down into a pink, green, and blue forest. He was met by a trove of soft corals, feather stars, and sea slugs; there was more to look at than he could possibly take in. By the time he surfaced, he knew that he had found what he was looking for. Little did he know then this Eden would one day become one of Fiji’s last remaining pristine reefs.

Moody was not a middle-aged man in the throes of a midlife crisis. He was not trying to escape from a suburban life gone dull. In fact, he had lived the island life before, on Pidertupo Village, a three-acre island in the San Blas archipelago off Panama’s Caribbean coast. He and his wife Joan first came to Pidertupo in 1966 at the end of a five-year quest to find an island they could call their own. He had loved and then lost this life, and was in Fiji to try to rebuild it.

Unlike the stereotype of tropical island owners, the Moodys weren’t monied people. They were blue collar Pennsylvanians who financed their travels through seasonal work at recreational parks and hotels. They set up their own resort on Pidertupo. Their resort was a no-frills kind of place that particularly catered to scuba divers. It also happened to be the only resort in San Blas, so, despite the lack of amenities, it attracted high-profile clientele such as members of the Roosevelt family, JFK, Jr., Timmy Shriver, and Gregory Peck. But, along with the positive attention the Moody’s received, they also turned a few heads that were less pleased by their success. On June 20, 1981, it was made it clear that certain people wanted the Moodys gone by whatever means were necessary. On what started out as another tranquil island night, they came, destroyed the resort, and left Moody for dead.

Moody had never been good at staying still. He traveled across Europe by motorcycle in the early 1950s while in the army. When he returned to the States, he became passionate about skiing and spent winters living close to the slopes in a converted Volkswagen van. He was ever-ready for adventure and was good at finding ways to put the plans he concocted into play. In 1957, he heard about the emerging sport of scuba. It was something new and different and over the edge of comfortable. He had to try it. He bought a tank and a regulator from an army surplus store and headed down to Pennsylvania’s Monongahela River to give it a whirl. Long before the existence of classes and certifications, Moody strapped on a mask and simply jumped in the water. Besides an underwater junkyard, there was not much to see. “You knew you were on the bottom when it got more difficult to swim—the muck got a little thicker,” he recalls.

They spent the next few years shuttling back and forth between Pittsburgh and the Caribbean as they continued their search for Eden. When their daughter, Marijo, was born, she became one of the crew. Six-month old Marijo spent 1964 sleeping in a box crate that once held an eighteen-horsepower engine.

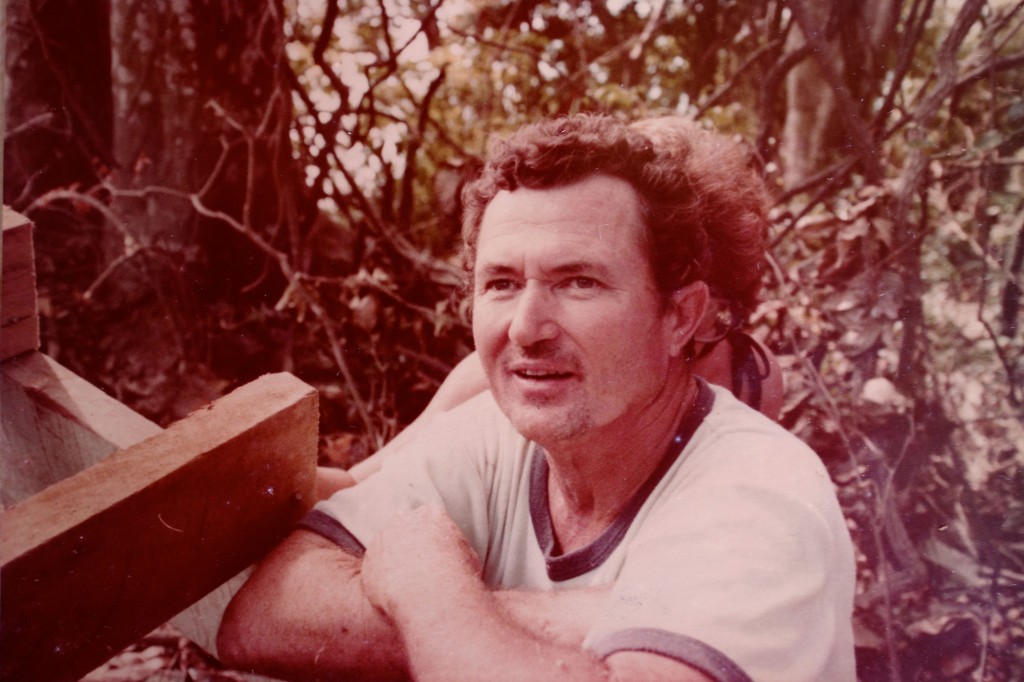

The lifestyle toned Moody’s muscles and blonded his curly tousled hair, prompting his wife to brag in her letters home about how good her husband was to look at. Joan stayed slim through cigarettes and daily swims, and the sun turned her Italian olive skin a luxurious brown. But despite the appearance of a glamorous life, the work was hard, and their days there were long. It wasn’t until after dinner that Tom and Joan would have a moment to themselves. From the porch of their beach shack they would go out and sit beneath the stars. “You don’t see that many stars up north,” Joan wrote her family back home. “See quite a lot of falling stars. It’s so beautiful on moonlight nights as you can see the many colors of the flowers and the moon reflecting off the water.” They would sit in the dark and softly talk of their future together. This is what they lived for.

During the next year’s travels to British Honduras, Tom Moody happened upon a book left by a guest at the fishing camp where he and Joan worked. The book contained descriptions of the San Blas Islands, an undeveloped archipelago off Panama’s Caribbean coast in the Kuna Indian Reserve. The Moody’s travel plans for the next year were set. In the fall of 1966, Tom, Joan, and now two-year-old Marijo took off from Pittsburgh in a Jeep pickup truck with an attached homemade camper and a trailer to tow their thirteen-foot outboard motorboat. They loaded up two bicycles, dive gear, and everything else they might need for a road-trip to Central America. “I don’t like to go somewhere and depend on other people,” Tom Moody explains. “We looked like the Beverly Hillbillies. It was tires strapped on and everything.”

When they arrived in the San Blas, the three-acre island of Pidertupo Village was everything they had been hoping for: small, tropical, and remote. These factors did not mean life would be easy—the nearest place to get supplies was two days away by sea. They would need to build infrastructure from scratch. But the Moodys were undaunted. They worked with the Kuna to negotiate a lease and set up shop. The first few years they still shuttled back and forth every fall and spring to maintain the steady income from their mini-golf and archery park back in Pittsburgh. They celebrated Christmas of ’67 with the flush of their first toilet. It would not be long before they could take in their first guests.

“I just got lucky,” is generally how Tom Moody reflects on his successes. “The funny thing was, I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I just wanted to do it.” The Moodys were unsure how to promote their five-room resort once it was built, but something about the seclusion of the San Blas caught on. It wasn’t long before newspapers in America were running pieces on their resort. The 1970s marked their glory days. They had a steady stream of guests and celebrity clientele. But their success also caught the attention of Manual Noriega, soon to become Panama’s infamous military governor. The United States would eventually remove Noriega from power, and he would be found guilty on eight counts of drug trafficking, racketeering, and money laundering. But before that particular history played out, Noriega visited the Moodys’ resort three times. Moody thinks Noriega was checking out what these Americans were up to in the middle of a possible trafficking route.

Some believe it was Noriega who ordered the attack. Sometimes, good luck and bad are hauntingly intertwined.

His shredded left leg was tied to his neck. He was dangling from a coconut tree, drenched in a toxic combination of gasoline and his own blood. Tom Moody watched his home and life’s work going down in flames and did what he had never done before: he gave up. “Why fight it anymore,” he thought as he felt himself slipping into unconsciousness. “I’m dead anyway.”

Joan was tied up on the beach just a little ways off. She had watched as a dozen bandits circled around her husband less than an hour before. “Moody go—now Moody go!” one of them had shouted before pulling the trigger of the gun aimed at Tom.

As some men poured gasoline over Tom, others had tied up Joan’s wrists and dragged her down the beach, leaving her there as they went to wreak further havoc. Ripping off the line, she began to run until two other men tackled her.

Joan pretended to faint and waited for the men to get back on their boats and leave before she got up again. She ran over to her husband.

“How badly are you hurt?” She cried while caressing his face, bloodied by the butts of the marauders’ guns. “They shot me in the leg,” Moody croaked out. Joan put her hands on his abdomen. “Not here?”

When he replied “no” she clicked into action. She didn’t follow her husband all the way out here from Pennsylvania and dedicate her life to building their dream in order to surrender. “Goddammit, you’re going to live!” she shouted, running toward the radios in their office. “No one dies of a bullet wound in the leg!”

Tom Moody did not die, but the gunshot he took left him without a calf and only half a tibia on his left side. Over the course of eight operations back in Pittsburgh, doctors took bone from his hip to replace what was lost in his leg. Lying in his hospital bed, Moody still thought he was pretty much a done man. Fifty-two-years-old, no formal education or training, his home and nearly his entire life savings lost. And to top it off, a gimpy leg. He could not imagine what his next move could possibly be. “What the hell am I going to do with the rest of my life?” he remembers thinking. “You don’t start in your mid-fifties. The energy and enthusiasm of youth is mostly gone.”

It was up to Joan to figure out what to do. “What are we going to do when the money runs out?” she asked Tom. “I don’t know,” he said. His stock of whimsy had run out.

Joan knew they could never go back to Panama and she had no desire to return to any part of Central America. But there were other tropical, pelagic areas in the world. She started going to the library and checking out books on the South Pacific, bringing them home and casually handing them off to Tom. As expected, her husband read and read. And by the time he was through, he announced that Fiji was the only thing that made sense.

In the fall of 1982 Moody bought himself a plane ticket to Fiji. Because the budget was tight, Joan and Marijo stayed at home. He stepped off the plane into warm, sultry air, and he could tell the ocean was near. He was on a quest once again.

When nothing panned out after nearly a month, Moody was ready to jump ship and try the Marshall Islands instead. But when he heard three independent groups describe Namenalala, he decided that it would be worth a visit. Part of him was skeptical as he approached the dragon-like island. But after scoping its shores and diving its reef, Moody was convinced that fortune was back on his side.

Namenalala’s owner was a member of the Kubulau, a native Fijian community that lives on the island of Vanua Levu, who maintains the waters around Namenalala as their Qoliqoli—the community’s traditional fishing grounds. The community had hoped to lease the land but had not been able to do so — most developers thought it would be too difficult a project to undertake. But Moody, confident he could work around the obstacles, visited the tribe and began to work out a lease. With the negotiations underway, Joan found managerial jobs for herself and her husband at a resort on the Turks and Caicos Islands in the Caribbean, and the Moodys began working there that April. But after years of being his own boss, Tom Moody could not stand working on someone else’s terms. It was not two months before he left the job and returned to Fiji. Joan stayed in order to save money to put their daughter through nursing school. She told her husband that she was not a kid anymore; she had already done the whole camping bit twenty years prior. She promised she would join him once he could put a roof over her head.

With the help of a local crew, Moody got down to business putting up the first building and a system of tanks to collect rainwater. By April, Moody called his wife and said he was ready for her.

Tom greeted Joan in Savusavu when she arrived on a hot, still day. She bought a dozen live chickens to feed the workers on Namena, and loaded them on the boat under a tarp with the rest of their cargo. The chickens squawked loudly as the Moodys set out on the glassy seas, but quieted as they approached Namena. Joan’s heart sank as the boat pulled up to shore and she took in the wildness of the island. Red-footed boobies and frigate birds darted above the hills. There was thick jungle and guano-covered rocks. But she did not say a word. In fact, she waited decades before she revealed to her husband that she had thought he had really “tipped his top.”

As they began to unload the cargo, they discovered what had quieted the hens: half of them had died under the tarp. Taking it in stride, Joan served up a huge stew of chicken and vegetables for dinner.

Over the next fourteen months, Joan ran the kitchen while Tom oversaw the crew as they finished the construction of a six guest cottage and a kitchen. They cleaned some stretches of shoreline into white sand beach. When an underwater volcano spat pumice onto their shores, they spent days cleaning them up again and incorporated the rocks into their septic system. They rebuilt their dining room roof when not one, but two cyclones destroyed it.

On June 1, 1985, Moody’s Namena Resort officially opened. The Moodys finally settled into a familiar routine of island life: Joan took the helm in the office; Tom made daily rounds fixing things and making improvements. They both enjoyed the ocean, the wildlife, and the family-style meals with their guests. Every evening they sat in front of the open window and watched the sun slowly dip below the sea.

“Financial success is the biggest destroyer,” is one of Tom Moody’s most used quips. Over the next decade, he and Joan watched as Fiji’s waters were overfished, and pilot whales and sea turtles became increasingly rare. Joan and Tom spearheaded an effort to protect Namena’s reefs working with the Kubulau. In 1997, a marine protected area was established around the island, prohibiting fishing and regulating scuba diving. As global warming, ocean acidification, and overfishing has left many of Fiji’s reefs in dire straits, Namena still boasts some of the best diving in the world. To many of Moody’s guests, diving Namena feels like a dream come true. In a way, it is this dream that saved Tom Moody’s life. But now, more than thirty years since he first arrived, he has decided that it is time to let that dream go.

I first met Tom Moody on Namenanala in March, 2013, three weeks before he left the island for good. He was 84 years old, round-bellied, hard of hearing, and slow to move, but still sharp as a tack. He still had an infectious twinkle in his eye. He still spent his days pondering the best ways to improve the resort, but could no longer enact the solutions himself. He could look out his favorite window and watch his guests dive in the reserve, but he had not been in the water himself for years. He could lie in the bed in the cottage that he built, but he could no longer sleep through the night. Instead, he came out to the front porch and looked up at the stars, fixing his gaze on the Southern Cross.

After lunch one day, Moody told me that he had received a letter he wanted to share. “You may find this a little strange,” it read. “My wife and I spent a few days with you in 1996. She passed away today. We are convinced that the heaven she has gone to is Moody’s Namena. Thank you for our wonderful memories.”

“He sent it the very day that she died,” Moody remarked. “Is your version of heaven Namena?” I asked. He paused. “Yeah. Yeah,” he said. “My wife’s right out there in that flower garden.”

Tom Moody was visiting the States three years ago when Joan woke up in the middle of the night struggling to breathe. Hours from the nearest hospital, there was not much that could be done. In these circumstances, one of Namenalala’s finest qualities became its worst one. Joan Moody died that night.

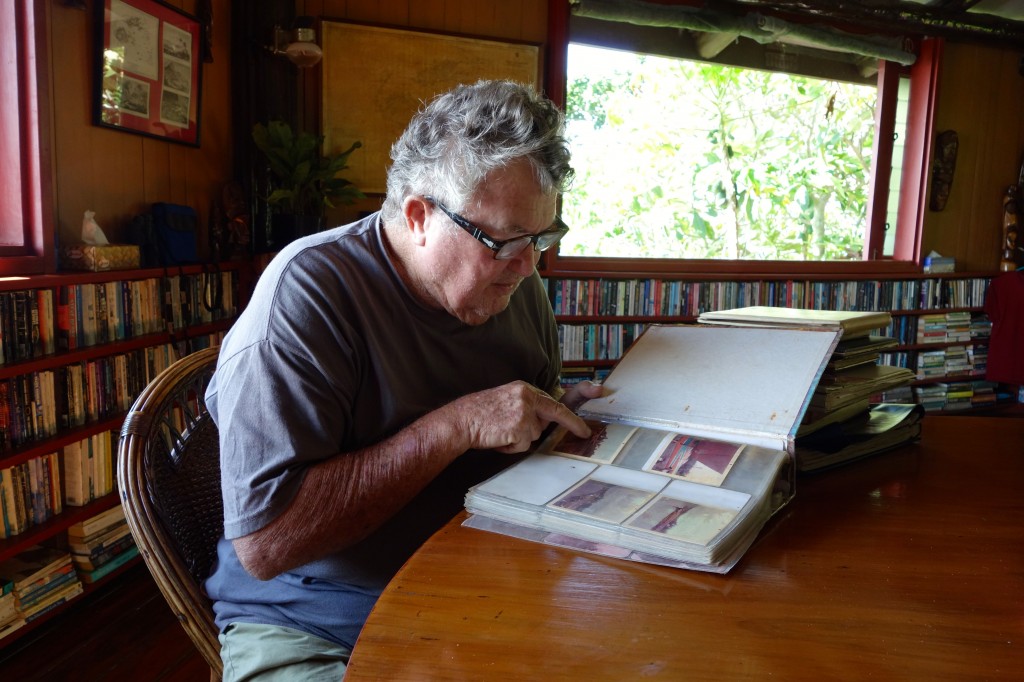

In a stifling July afternoon, I sat with Tom Moody in the suburbs of Pittsburgh. We were five minutes from the nearest gas station, ten minutes from McDonald’s, and fifteen from the big box stores. Since moving there from Fiji, Moody does not venture out too far. Baileys on ice in hand, he shuffles from the kitchen to the dining room table, covered with dusty photos, faded magazine clippings, and musty papers. All that is left of the life he led over the last thirty years.

Moody is quite practical about his return to Pennsylvania. Acutely aware of his own fragility, he knows living with his daughter, now 49 and a nurse, makes a lot of sense. It was a move that became inevitable when his wife died. He first put Namena on the market in 2012. After not finding much interest, he finally struck a deal with a Canadian investor in February 2013 for about twenty percent of what he had originally asked. He is sensible about what he will do with the money, with plans to save enough for impending medical bills and to leave some behind for Marijo.

But recently Moody’s been feeling a familiar itch, the one that started it all the last time he found himself living in Pittsburgh. He could not help himself but dream up a new plan. “I want to get a small camper and travel the small roads of America,” he says. “Not on interstates, just on two-lane roads.” He thinks he will start in the Shenandoah Valley. “That’s a wondrous place in the fall. They’re pressing apple juice for hundreds of miles, and you can just smell it all the way down the highway.”