“Hollowed” is a work of fiction based on true incidents/accidents pertaining to now banned rat hole mining practice followed in Meghalaya, a north eastern state of India. Still practiced illegally, it attracts and employs undocumented and poor workers from neighboring states and Bangladesh. Relatively higher wages allure people to work in rat hole mines in unsafe and risky conditions. It has led to widespread pollution of rivers, and deforestation. It was banned by India’s Green Tribunal in 2014.

✵

I’ve always wondered if it’s the people who give the place its character, or if it’s the spirit of the place that settles down in the people inhabiting it. This was particularly true both of Meghalaya, a small eastern state of India, and of Bali, our tour guide there.

When I think of Meghalaya, I think of a dark blue car darting along a snaking mountain road, of golden sunshine lighting up thin veils of clouds, revealing the lush, green peaks of the Garo hills. I think of white, wispy clouds that could become dense and dark in just a few short hours before rapidly releasing torrents of cold rain. I think of a serene wonderland, rich with subtropical green forests, abundant waterfalls, sparkling rivers, deep limestone caves, living root bridges, and refreshing rains. I think of coal fields, I think of Bali.

A mountainous region encompassing the Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia hills, Meghalaya is the combination of two words: megh, meaning clouds, and alaya, meaning home or abode. Meghalaya was indeed an abode of the clouds.

“Hey Manaswini, the tribes in Meghalaya are matrilineal. I think you should settle down here.” I remember Vaibhavi teasing me when we landed in Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya.

Sometimes, you think back on memories and those memories in turn open up something in you. I distinctly remember Raja, Vaibhavi, Raghav, and I in that blue car with Bali. We had stopped for a short break at a restaurant perched on a hilltop in the Khasi hills when it had begun to rain. Bali had remarked, “Rain again! You know, Manaswini ma’am, you eventually hate having too much of anything, except for money, of course.”

Too much money! How much money is too much? Isn’t it always a bit too little? I silently concurred with Bali’s statement as I admired the resplendent beauty all around us. After just a few minutes of heavy rain, the sky was clear again.

“Meghalaya is so beautiful and pristine!” I exclaimed, taking a picture of the enchanting valley beneath a foggy mountain. “You never get this soul-piercing rawness in the city! Development truly destroys beauty.”

“So, what are you saying ma’am? There shouldn’t be any development? People living here also seek the same comforts as you, but we don’t have the opportunity.” Bali’s calm voice had a hint of bitterness. “We too need food, clothes, education, medical facilities, good houses ‒ how should we get that if not with development?”

I was slightly taken aback by Bali’s remarks. Instead of concurring with my adulations and observations, he’d snapped back with a controlled fury.

“Do you not make enough to feed your family?” I asked, sipping the fresh pineapple juice that had been placed on the bamboo table.

“As a tour guide? No, ma’am. It is seasonal and too unpredictable. I have two sons and a daughter. The money from this job is hardly enough.”

Was this a story to squeeze more money from us than what we had agreed upon? I later shared my concerns with Raja, Vaibhavi, and Raghav as Bali smoked at a distance. Thick lines dominated his forehead and his small eyes were lost in some nameless worry.

“Who cares what he says? We’ll pay what we agreed upon. Just ignore the sob stories,” Vaibhavi comforted. Meanwhile, Bali ground the leftover cigarette butt with the heel of his old shoe, coughed, spit in the bush near him, and started walking toward us. By the time he joined us, he was jubilant once more, eagerly waiting to take us to explore the less prominent, less crowded, but most enthralling parts of Meghalaya.

The more I came to know of Bali, the more intrigued and enamored I became with Meghalaya and the people who lived there. He wasn’t manipulative or silver-tongued; while my other friends kept their interactions with him to a minimum, I found him too earnest to just “ignore.” Unlike most of the tour guides I’d met up until now, he had an honest, even brazen, demeanor.

“So, ma’am, would you like to see more of the ‘beautiful rolling greens of Meghalaya’ or would you like to get a taste of the real life that people lead here? No tourist wants to see the schools and hospitals of this ‘beautiful’ place.” His acerbic question put off everyone in my group, including me.

“If it would help you or anyone else, then sure why don’t we see it? People’s lives aren’t shows to be watched and forgotten, right? And by the way, isn’t Meghalaya industrially backward because the people here chose it to be so? They want to preserve the culture, the traditions, and this heavenly nature’s retreat? Isn’t that the reason that it’s a protected state? So, I don’t really understand your complaints.” The exasperation in my tone didn’t infuriate him further; on the contrary, he gave a sincere smile of appreciation.

“I’m very impressed ma’am. You know so much about our Meghalaya, even more than the people living here, even though you live so far away in Amreeka. You don’t, how we say, just skim the book, you read every word and try to understand our story. I would try my best so that when you leave this place, you would take the real Meghalaya with you, not the “showcase” version we sell to tourists.”

At this, Raghav, Raja, and Vaibhavi started teasing me. “Hear, hear to our one and only, who reads the words and skims them not.” Bali smiled and blushed upon hearing their chorus as we all walked back to our car.

“How long have you been doing this, Bali?” I had asked.

“What?”

“This tour guide thing. I bet it can’t be your only source of income if it doesn’t come with good money, right?” I jovially responded.

He had laughed. “Yes, ma’am, that’s true. But I haven’t been doing this for very long. Just two years.”

“Really, what did you do before that?”

“Oh, Ma’am! My story is boring and depressing. Not worth a penny to anyone.”

“That’s fine! We have no pennies to spare anyway.” I grinned but he went quiet. I sensed a shadow of sadness interrupt his train of thoughts.

“Bali, come on!” I had prodded as we all sat in the car, “Sharing helps. It unburdens your mind.”

In response his face tightened and he stayed quiet. I felt like I was forcing him into sharing. So, it was best that I stopped pestering him.

“It’s okay Bali, you don’t have to share if you don’t want to. I was nudging because it’s a long drive, you know, and I love to hear‒”

“Have you heard of rat-hole mines, ma’am?”

“Not really…why, did you mine coal before?” My eyes widened. I had never met a miner before.

“Well, I was…I was connected to it.” He hesitated, then continued, “Our lives are dependent on coal, ma’am. It’s the lifeline of so many of us here in Meghalaya, from the private mine owners to everyone down the chain, from the workers employed to do the mining job to the transportation crew of truck drivers. You know, coal is called ‘black gold.’ It’s transported from Meghalaya to the neighboring states of Assam, or to nearby power plants. It’s a common fuel for running the local limestone processing factories. But everything changed after the ban on rat-hole coal mining, everything was finished.” He looked grim and seemed lost.

“But why? Why was the ban imposed in the first place?” He didn’t respond. Raghav then turned to me. “Here, check out this article.”

“What is it?” I gave him a puzzled look.

“An article with the details of rat-hole mining.” He tilted his phone toward me.

I read the whole article, aghast. “Bali, did you do rat-hole mining?” I asked suspiciously.

“Rat-hole mining isn’t bad ma’am. You dig only what is needed. Unlike open-cast mining, our hills stay the way they are. The forests remain intact. A lot of people get to live a good life.”

“What on earth is wrong with you? A lot of people doesn’t mean everybody. Even if the hills stay the same from the outside, aren’t you emptying them from the inside? What will everyone do when the hills run out of coal one day? Don’t you find anything wrong with the inhumanity of the way this mining is done? The damage to the environment? There’s a reason for the ban on rat-hole mining.”

“This is how we have been mining traditionally for years, ma’am. We take care of our environment. I can show you, ma’am. You should see those hills. You wouldn’t even know that there are these mines inside these hills.”

Bali had piqued my curiosity enough to displace my anger. “Can we go, then? Can I see those hills? Those mines?”

“Hills yes, but mines? Maybe not, ma’am. It’s illegal, you know.”

“Come on Bali, I’ve come from so far. I’ll pay you extra.”

“No, ma’am, it’s not about money. I am not a greedy person. It’s about your safety.” He replied flatly.

I sighed. “Fine, you decide, Bali. I won’t ask you to compromise on your values for my thrill or pleasure of sightseeing.”

He looked unsure, but after pondering for a while, he reluctantly agreed. “Just one mine, ma’am.”

Impressed with my “powers of persuasion”, Raja and Raghav gave me teasing glances once again. Vaibhavi winked and I smiled. On our way to mines, we drove through the deep forests of Sal and Teak trees, stopped intermittently to photograph the numerous rivulets and waterfalls, wild orchids and pitcher plants. We finally turned onto a gravel road with huge, black mounds piled on both sides.

“What are those?” Vaibhavi asked as she tried to capture them in her camera.

“That’s extracted coal, ma’am.” Bali motioned with his hand. “Please no pictures. Otherwise we will have to turn back right away.” We continued driving.

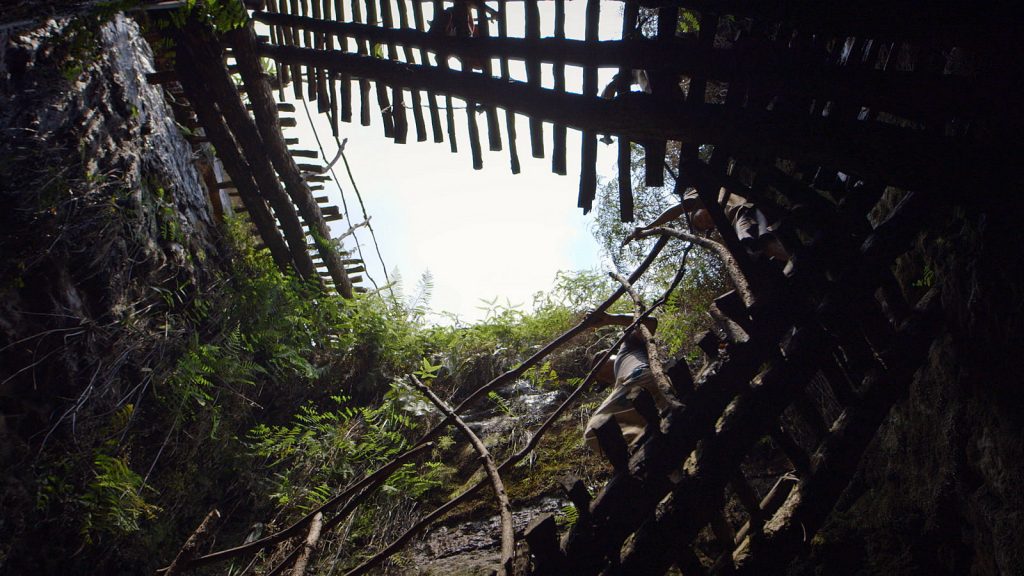

Finally, we all stood at the rim of a deep trench among the green, forested Jaintia hills. After I soaked in their beauty for a few minutes, my focus went back to the trench that lay before us.

“How deep is it?”

“About one hundred and seventy feet deep, ma’am.” Everything that the articles detailed was right there, before me. The article said:

Deep trenches had to be dug in order to reach these tiny mines. Some went up to two hundred feet.

“Wow! And are these pits just left open after the mining is done? Where are those small horizontal tunnels dug in the walls of hills?”

“You see that wooden staircase? It runs diagonally through that wall, from where you can get access to those horizontal tunnels.” He pointed.

“You mean rat hole mines?” In response, he shrugged.

I looked in the direction he pointed and the description of the article floated vividly in my mind.

A staircase made of bamboos descends diagonally through the wall in a zigzag manner for miners to descend and reach the rat-hole tunnels. Once in the mine, some would extract the coal, some would fill the boxes with coal extractions, and others would drag these boxes to the shaft which would pull these boxes up to the surface from where they were moved to storage sites until they were delivered to their final destinations.

I lifted my camera to my eyes, and he protested again, “Sorry Manaswini ma’am, no photos, please. I’ve risked a lot to bring you here.

I stared down the pit and then at the bamboo staircase lined up against the hill; I felt uneasy. “Miners walked down that flaky staircase! What happened when it rained? It must’ve been so slippery.” My shock evoked a smile to his lips.

“There are many more risks than this, ma’am. But yes, that’s just the beginning.”

“Is this an active mine?” Vaibhavi asked.

“No, it has been abandoned. I told you, it’s illegal to do rat-hole mining now that there is a ban.”

“But we saw large mounds of coal on our way to this place! Why would you have those mounds if people were still not mining, albeit illegally?” she insisted.

“That’s old coal, Vaibhavi ma’am. It’s not illegal to transport the coal that we mined before the ban,” he countered defensively.

I looked around. It was quiet, peaceful, and secluded. The nearby trees were dancing to the tunes of misty winds.

“There’s nobody around. Can’t we just go down and take a quick look inside one of the closest mines. Please…please…” I almost begged, my pleading amusing my friends. “Nobody would ever know that we were there. Please!”

“What if something goes wrong, ma’am? What if you slip and fall in that pit? Like you said, that bamboo staircase is indeed slippery.”

“I’ll be careful. Besides you’d be with us. If you sense there’s danger while we descend, we won’t go further down.”

“But what if you slip? Just to remind you, what I’m doing now is also illegal.”

“Agreed, Bali. You have a point. But I don’t see any sign which warns about not going into the mine. Let’s say I do fall in the pit. There’d just be a small headline in the newspaper: ‘Reckless American Tourist Dies While Exploring the Banned Rat-Hole Mines.’ That’d be a nice way to end life, you know.” I joked, darkly.

He laughed. “Ma’am, you have a bad sense of humor. All right, if you insist. But only two of you can come. The other two need to stay up. Please bring your cellphones and water bottles. And if something goes wrong, you’ll be on your own. I’ll run away.” His face was hard.

I smiled. “All right. I am fine with your running away and leaving me here to die.” His softened face showed that my response evoked some sadness in him.

“Ma’am, I have a wife suffering from cancer. I have done some bad things…but now I want to atone. I guess it’s too late for that but…come on, let’s go. At this point in life, I don’t want to take even a calculated risk.” But he had taken a risk by agreeing to take us to the rat hole mine.

Vaibhavi didn’t want to come down and Rajan stayed back with her. Raghav and I followed Bali. The bamboo staircase was indeed slippery. Bali effortlessly descended, and waited for us, while I trudged down it like a toddler, Raghav behind me.

As we walked, I imagined people carrying baskets and boxes, scurrying up and down these stairs, their bodies and faces covered black with coal dust and their gleaming, white teeth the only bright thing about their dark existence. By the time we had reached the first rat-hole, I already felt tired. A single look at the entrance filled me with awe and shock. I’d read about it, but something about actually seeing a miniscule, four-foot entrance to a pitch-dark tunnel with howling wind gave me shivers.

“Wow, I can see why only kids or shorter people were employed as miners. How can you go in and out with all that coal? And how would you crawl through those dark coal tunnels with all that mining equipment?”

Bali smirked. “Teamwork, Manaswini ma’am. Once we get inside the mine, some of us would extract the coal with axes while lying on our backs. We would collect the droppings of coal in a box between our legs. Others would drag these boxes back to the shaft and then the boxes would be pulled up to the surface.”

A wave of anticipation took hold of me, tempered by a subtle sense of dread. “Uh! Can we go in?”

He smiled sarcastically, “Are you taking my permission?”

“Believe it or not Bali, yes, I am. Would you lead the way, please?”

“I never said that I would…” As he trailed off, I could see that Raghav was annoyed by his response.

“That’s right. You never did say that,” he said to Bali and then turned to me, “Go ahead and get in. I’ll follow you.

Just as I was about to do so, Bali intervened and hopped in before me. “Wait! Let me lead the way!”

“Okay, what caused this change of heart, Bali?” I teased him as I crawled in after him.

“You’re impossible ma’am. You remind me of Karuna in her good old days.”

“Who’s Karuna?”

“My wife.”

As I felt the hard, rough floor rubbing against my knees, his words evoked a strange sadness in me. I touched the walls, which were clear of coal now. Daylight was reflected on this part of the wall, but I could see almost nothing further ahead. It was only darkness, and the roof seemed to get lower and lower the further inside we went. “What if the roof collapses on me?” I muttered.

“Ma’am, that’s always a possibility.”

I suddenly felt uncomfortably stifled. “Why would anyone in the world crawl in this horror, Bali? It’s so… so suffocating!”

“For money, ma’am.”

“Well, how much money would it be?”

“About 1500 to 2000 rupees, ma’am.”

“That’s around $20 to $30. And that’s a lot of money, you say?” My eyes widened with shock.

“ Yes, ma’am. On an average people make 300 rupees around here. So for us, that’s a lot of money. Very hard-earned money.”

By now, I was panting, feeling dizzy and claustrophobic. I struggled for air and suddenly wanted nothing more than to be out of that dark, damp, and suffocating place.

“Raghav!” I tried to scream but only a muffled voice came out…

“I’m right behind you.”

“I can’t breathe! I need to be out!”

“Ma’am, don’t panic,” Bali said. “We aren’t that far from the opening. Just crawl backward.”

I tried but somewhere along the way, I lost consciousness. When I did, I woke up to a cloudy sky and green trees, my face wet, Raghav kneeling with the water bottle in his hand, and Bali fanning his shawl over my head.

“God! I’m so relieved that you aren’t dead. How are you now?” Raghav asked.

“Better! And I won’t die that soon,” I tried giving a reassuring smile, “You pulled me out?”

“We had to carry you ma’am,” replied Bali as he and Raghav helped me to stand.

“Are you okay now? Shall we move?” Bali asked.

“Unless you want to take another peek in that forbidden black hole?” Raghav winked as he took my arm and helped me walk.

“The first option sounds fine,” I responded. “Can I have some water, Raghav?”

“You gave us a scare ma’am,” Bali complained, “I was regretting my decision.”

Gulping all that water hadn’t helped me to shake off the eerie feeling I had from the mine. “I don’t know how anyone could do this for money. Tell me, did you also do this, Bali?”

“Ma’am let’s start moving out of this place if you are feeling okay. I can narrate my story on our way back.” Bali was becoming tense again. He was fearful of getting caught, a sense of regret and guilt, but why?

I got up and we all started to climb up the makeshift staircase of bamboo poles. As we walked steadily, no one said a word for few minutes. The creaking of the staircase was the only sound.

Then Bali coughed and began to speak in a slightly choked voice, “I started working in the rat-hole mines with my father when I was twelve. I was very scared at first. I was the fifth child in my family. My two older brothers were also miners.”

“At twelve! What happened to going to school?”

“I stopped going after seventh grade. I was never smart in studies. And between earning money and school, why would anyone like me choose school?” He sighed as he concluded the sentence.

“What made you stop doing this?” I asked between taking deep breaths. In response he took another deep sigh.

“What made me stop? It was an accident, ma’am, one of the many accidents. I was inside the mine at the time, when the chain of the crane shaft carrying the coal broke. My father and my two brothers were crushed by the shaft that fell. About twelve people died that day. It was also my first time witnessing death, you know. First time realizing that people could be lost forever. You know how a tender vine needs the support of a branch to grow? I felt like I was uprooted and left on the ground to shrivel up and die. And some part of me did shrivel up and die.” He went quiet for a few moments before continuing. “But I survived. We received some 75,000 rupees as compensation.”

“Just a thousand dollars?” I was shocked again.

“It was a lot of money back then, I was told. Enough to forget the death of my father and brothers. I was sixteen at the time. But I decided then and there, I would not be doing this anymore. That was also the time when I met Karuna…” He wiped a tear sticking to his eye and swallowed whatever was choking his throat. We continued to retrace our steps, carefully and slowly. The images of children, women, and men rose up in my mind again. I saw them tracing this same path, up and down, up and down, almost every day, carrying coal baskets on their backs. The chains and the falling shaft became alive in my mind. I couldn’t ask if Bali’s father died on the spot, or if he was taken to a hospital and that was where he had died.

I asked, “What did you do after that? Did you go to school?”

He laughed, “Ma’am, I wish I did. I wish I had that sense. But, you know, I had suddenly become the oldest male member of my family. Luckily, I made friends with the right people while working in mines, some contacts good enough that workers from outside could be brought to keep the local people safe. And then I didn’t stop until…”

“Until…?”

Now, he was talking to himself, “I made good money. My children go to a good school. They are not miners. They will have a better life than me. It was all for a good reason. Who does not sacrifice for their family?” He sounded as if he were trying to convince himself along with us.

Now, I understood. Bali used to be one of those despicable brokers who arranged for undocumented immigrant laborers to come be miners instead. I couldn’t prevent a sense of aversion towards him seeping in.

“What changed Bali? I’m sure the ban wasn’t something that would have deterred you.”

“You think you know me, ma’am?” The bitterness in my voice had a vitriolic effect on him.

“I guess I know a little bit of you…” I trailed off.

I thought our conversation was over, but he began again after a brief pause, “Just shortly after the ban was imposed, some fifteen children got trapped in a flooded rat-hole mine. They all drowned.” Bali went quiet again.

We all walked up in silence. It had begun to drizzle again.

“Died in a flooded rat hole mine! How did the mine get flooded? By a drizzle like this?” My tone was fiery.

“You have all rights to hate me ma’am. But yes, a continuous drizzle like this does fill the empty tunnels with water. Sometimes from rain, or from a trickling waterfall, or a flooded river nearby. But the miners are not sent to flooded tunnels. It so happened that the young miners while axing coal accidently knocked down the wall of an adjacent, flooded mine. After which they fell victim to the rage of the water.” He paused again reliving the past, then he swallowed and continued, “The water drowned everyone in it.” Bali was barely audible as he completed his sentence.

“How old were the kids?” My voice was choked.

“Between thirteen and seventeen. They all came from poor families from across the border in Bangladesh. We didn’t even know about it for days. It was monsoon season and it was raining a lot.” Bali walked with his head bowed.

Perhaps he too thought about those kids who left no legacy behind. Nobody knew their names; nobody would ever know. Nobody knew their hopes. A long dark tunnel with black walls that was quickly filled with cold water—the earth was the only one to witness this cruel mingling of past and present.

Once more, I felt dizzy and nauseated. As I rested along the pole on the staircase and took some sips of cold water from the bottle, I could see the small figures of Raja and Vaibhavi up on the rim waving at us. Raghav and Bali waved back to them. I didn’t. I couldn’t.

“So, did the mining company provide any compensation when all this happened?” Raghav asked.

“No sir. Compensation for mine deaths happens only if the accidents come to light, but there are so many mines and so many undocumented immigrant workers, that many times, the deaths not even registered. Lives just disappear in some cold, dark trench, and their families wait …forever I suppose, or until hopelessness or death consumes them too.” Bali said wiping his wet face with his shawl.

We were at the top now, back to the rich green view of the aesthetic, peaceful, serene hills. You could never know that they were covering up countless, hollow rat-hole tunnels within. I looked at Bali, another guilty, living embodiment of this contrast.

I was quiet on my journey back. Bali’s concerned eyes peeped from the rear-view mirror, “Ma’am, are you okay?”

I nodded my head in affirmation and looked outside. Such beauty harbored such helplessness! Raghav narrated the rat-hole mine experience to Raja and Vaibhavi, and I looked at Bali with disgust. I searched, as we all do, for a way to get away from the uncomfortable truths of life. I searched for someone to blame, to knock off the pain heaving on my chest.

We stopped for refreshments at a small restaurant. Bali bought tea and cooked rice flakes for me. “Chai and poha for you, ma’am. I’m sorry if I offended you. I did everything to make your trip memorable. Even flouted the rules of the tour company.” His voice was soft and sensitive.

But, honestly, I didn’t hear what Bali said, but asked him a question that was bothering me, “Were you involved in bringing in those kids who died in that mining accident?” My question was perhaps judgmental, ready to undo every effort Bali had made to make our trip memorable.

He didn’t answer but kept the plate and left. As the trip continued, I felt pity replacing the aversion. I pondered over the complexity of human emotion as I thought about his hardships, his turmoil, his wife, Karuna dying of cancer, his kids and his dilemma. Yes, beauty does indeed harbor immense helplessness.

Once our trip concluded, we tried to pay him thrice as much as he had asked for, but he refused politely. “Ma’am, this money will help me. But I’m not alone. There are so many of us, all caught in our own web, trying to free ourselves but stuck to our decaying lives because there’s nowhere to go. I respect your help. You are good people. Here, take my phone number. Call me sometime, if you will. I’ll feel proud that someone called me from Amreeka. Remember me, ma’am. I’ll pray to Jesus for you.” Then with a glint in his sad eyes, he asked, “Can I have a selfie with you all?”

✵

This was about two years ago. Today, four years into the ban on rat-hole coal mining in Meghalaya, I heard that fifteen people were stranded in a rat-hole mining accident. Another coal mine flooded and nameless miners were trapped inside. There wasn’t any equipment with enough power to drain the flood water. The factors that had led to the accident – the inefficiency of the administration in initiating rescue operations, the political interests of local governments and bureaucrats and their ties with the private mine owners whose illegal mining operations were permitted to continue despite the ban – were all over the media.

Bali floated in my mind, his sick wife next. I tried to find out the names of the miners who were trapped inside, but there was no mention of them anywhere. People were even unsure about their number, as if a life or two here or there didn’t really matter. There were various theories about the flood, whether it was caused by the nearby river or from the drainage of water from an abandoned mine that was once tied to open pits and left like an open, festering wound.

I searched frantically for Bali’s number and made a call. After a few rings, someone picked up the phone. I was so excited at the prospect of hearing his voice, but the voice that answered was a girl’s.

“Hello.”

“Hi, can I speak to Bali?”

“Who’s this?” the voice asked.

“I am Manaswini. I live in California. Bali was my tour guide when I visited Meghalaya two years ago.”

“Oh! So why do you call today, ma’am?”

“Just like that. Who am I speaking to?”

“This is his daughter, Sophia, ma’am.”

“Oh, how nice, Sophia. Is he around? How’s your Mom?”

“My mom passed away one year ago, ma’am. And papa…he is…”

There were sounds of sobs from the other side.

“What happened? Is he very sick or something?”

“Worse, Ma’am. There was a mining accident here. Papa is inside a flooded mine, ma’am.”

“What? I thought he had quit that kind of job.”

“Yes, he had. But we lost a lot of money in my mother’s sickness, ma’am. He had taken up a loan and we needed fees for our college, so…”

“So…?”

“So, he decided to go just this last time…ma’am, he said that this would be the last time that he would go. Before he left he had joked, “I’ll make us rich this time.’” There were more sobs, and I knew that Bali would not be coming out alive.

This accident had gained enough limelight. And who cares what the names were of the people trapped inside the flooded mines? They were simply collateral damage, worthless to reckless economics and narrow gains disguised as cultural preservation.

If it were not for him and what happened to him now, I could have called this anything: a memoir, travelogue, a case study, report; but not now. Is there a prose version of an elegy?

I should have called earlier.