[satellite gallery=8 auto=off caption=on thumbs=on]

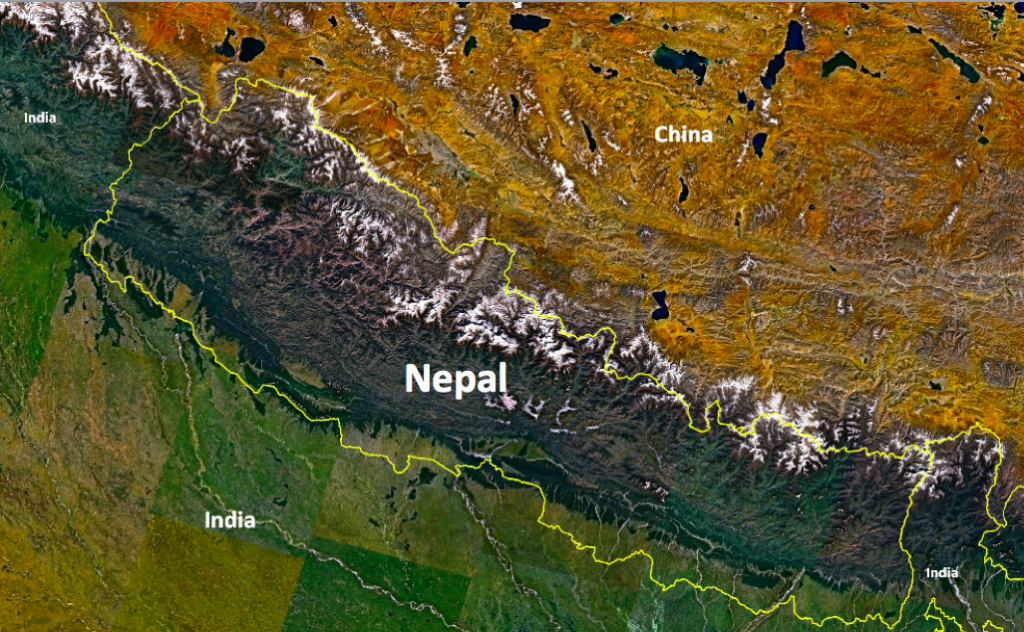

Nepal seeks to become a ‘hydropower nation.’ This is happening in some ways, and not happening in others. The photographs included in this essay were taken during ethnographic fieldwork conducted in the upper watersheds of the Trishuli and Tamakoshi Rivers—where a variety of differently oriented hydropower projects are in different phases of planning and construction. This visual data complements my larger and ongoing research project concerning patterns of social and spatial change in places and spaces affected and implicated by hydropower development in Nepal. By presenting an ethnographic account of Nepal’s hydropower frontier, this work hopes to increase the visibility of the spaces and places where the ‘hydropower future’ is both produced and lived – drawing the eye away from the centralized plans of Kathmandu, and toward the places and spaces of the hydropower resource frontier.

Hydropower has long been understood as the necessary future of Nepal, and the ‘need’ for hydropower exists large in the social imagination and as a central topic in political and developmental discourse. During the dry winter months, the unfulfilled promise of an estimated 83,000 MW of total generation potential hangs over Kathmandu like a cloud, while rolling blackouts consume the growing city of nearly three million people for up to eighteen hours per day. Hydropower development is imagined as means to resolve social and spatial urgencies and a force to drive economic growth, ‘to keep an entire generation from growing up in the dark’ while also ensuring that ‘not one drop of water should flow beyond Nepal’s borders without creating wealth.’

In recent years, the production of the hydropower future has been intensifying. As of August 2013 Nepal’s Ministry of Energy reported that 70 of 337 surveyed hydropower projects were at ‘advanced stages of construction,’ representing 1,978MW of power generation capacity This wave of development will triple the existing national installed capacity of 705MW in the coming years – yet still fall short of expected demand, based on trends of population growth, urbanization, and increased consumption. New plans are being made to produce the hydropower future, supported by a complex array of political, financial, social, and environmental mobilizations. Politicians talk about social justice and sovereignty, development organizations talk about scarcity and underdevelopment, the government talks about the welfare of future Nepalese citizens, financiers are actively seeking foreign investment, and the private sector continues to repeat that “Nepal is open for business.” Everyone knows hydropower is needed; everyone knows it is coming; no one knows when or how it is coming. It doesn’t seem to be happening – yet in certain places, the hydropower future is already arriving.

Importantly, making a ‘hydropower nation’ requires more than political clout, hydrologic data, cash flow statements, foreign loans, trucks, engineers, and concrete – it also requires the reorientation of livelihoods, political economies, and socialities specific to Nepal. Therefore, my research presents hydropower development in terms of the negotiations, turbulences, adaptations, and intermixtures that mark its fluid boundaries, and from the perspective of differently mobile ‘project-affected persons’ who are engaged in a variety of different future-making projects.

This ethnographic work describes the social dimensions of hydropower development in Nepal – it uses the watershed as the unit of analysis; it proceeds by walking upriver; it reorients itself situationally and relationally as it encounters the questions and concerns of others; it focuses on the unevenness and uncertainty of different kinds of change in ‘developing’ watersheds and the ways that differently people organize meaning within these changes. Thus, I hope to disaggregate abstract definitions of ‘locality’ and ‘affectedness’ by asking the question: What kind of hydropower development, and for whom?

My research describes the ways in which hydropower development produces new landscapes of risk and opportunity – simultaneously affecting patterns of empowerment and disempowerment, location and dislocation, connectedness and fragmentation. This study hopes to take ‘local impacts’ seriously while avoiding an essentializing view of ‘localities’ by emphasizing shifting flows and mobilities – tracing how labor, capital, information, artifacts, and imaginaries of hydropower development come and go from watersheds and communities which are oriented differently within multiple spatialities. Each project is a plurality of experiences with shifting boundaries: there is no one hydropower project, and there is no single ‘project-affected area’. Differently situated and differently mobile populations are affected by hydropower development in diverse and divergent ways. ‘Affectedness’ occurs most visibly where people are directly displaced from specific places where culture ‘sits’ – but it also occurs more subtly on mobile people and culture in motion; on cultural flows and mobilities themselves. ‘Affectedness’ itself is a layered and contested concept, shaped by positive and negative effects that are always and everywhere competing.

In the upper Trishuli watershed, there are 14 different hydropower projects in different phases of planning and construction, representing 838 MW of power generation capacity. In the upper Tamakoshi watershed there are 10 different hydropower projects pending, representing 1,617 MW of power generation capacity– including the 456 MW Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project, which is currently the largest built in Nepal. This volume of development is significant, and these are just two rivers among many in Nepal where hydropower is being developed. Yet despite the palpable imminence of Nepal’s hydro-future, it is important to recognize that hydropower development does not ‘happen’ as per central plans or master narratives—there are theories of hydropower development and there is the muddier praxis.

In the Trishuli and Tamakoshi watersheds, local responses to the processes of hydropower development are extremely diverse. In some areas people are boycotting public hearings and blockading roads; in other areas they are volunteering labor and purchasing publicly listed shares in the project – in some cases these are the same people. Some Nepalis desire social changes and the prospects for ‘becoming bikasit’ (or developed) that hydropower claims it can bring and others fear them – in many cases these anxieties coexist in the same household. Some people are materially content with the levels of compensation on offer, others are worried that compensation money will be gone in a year and there will be nothing to eat; some people trust their local leaders to negotiate with hydropower developers, others are sure that corrupt local leaders and contractors will ‘eat their money’ and local people will always be poor. Some accept the fact that their houses will be flooded, while others fear their villages will be destroyed by landslides triggered by tunnel blasting. Many people wish information was better; many people pride themselves on their efforts to collect information about the project (which is in some cases, considerable). Many people living athiprabhabhit kshyettramaa, or ‘in the ‘most-affected areas,’ are quite savvy in positioning themselves to solicit compensation, while others have no concept of how to approach the project, and feel powerless. This experience is intensely structured by social difference – by longstanding patterns of social exclusion and relations of inequality that operate along lines of ethnicity, caste, class, and gender. However, despite these inequities and competing values and interests, nearly everyone wants local jobs to put food on the table and roads to make the hardships of mountain life easier.

When hydropower projects arrive, things change fast – as the processes of hydropower development introduce new variables into the existing landscape of mobility, producing a complex intermixture of inflows and outflows. There are local people who get jobs for the hydropower contractors and those who do not; there are men and women leaving to seek work in Saudi Arabia or Qatar; there are others returning from years in Malaysia; there are Chinese contractors and laborers living in encampments; developers and machinists from India, and Nepalis from bahira and thala (outside and below) surveying, driving excavators, building roads; British development experts and Korean engineers; there are developers and manpower agents from Kathmandu; hydropower consultants from Norway and financiers from Japan; entrepreneurs from the borderlands of the Tibet seeking increased opportunities for cross-border trade; Australian lawyers, American and Danish researchers, and German development organizations; there are students returning from school in Delhi and NGO workers arriving to build schools; workers from the Tarai hired for the seasonal harvest; there are local community projects financed by Nepali diaspora organizations; trucks bringing new goods overland from China and ‘project-affected people.’ Again, the hydropower project is the site of intersection for many different kinds of social, political, economic, and imaginative projects of future-making.

As each project develops and others follow, opportunities and patterns for the deployment, exchange, and replacement of labor become more complex—producing a complex landscape of shifting patterns of work, mobility, access, and aspiration. Flows of labor, capital, and imagination are coming and going always, rushing into the watershed, churning and eddying for a while, then trickling or rushing away.

The positive and negative effects of hydropower development are interwoven and interpenetrating – risks and opportunities (or costs and benefits) are co-arising within the new geographies of Nepal, and there are no easy answers here. The material need for hydropower development is a real thing – a lived experience of scarcity with real implications and costs; a polyvalent problem of social justice that rightly warrants attention from projects that assert ‘the will to improve.’ Yet it is also true that development practices are extremely variable and imperfectly applied, that corruption persists, that methodologies for ‘stakeholder engagement’ and ‘benefit sharing’ are still evolving, and that Nepal remains an extremely unequal society – the production and distribution of the hydro-future has everything to do with power.

Again and to be clear, it is not my aim to support or oppose Nepal’s various hydro-futures, but to increase the visibility of the lived experience of hydropower. However, I do believe it is important and constructive to question the efficacy, equity, and sustainability of different models of hydropower development—and this necessitates making an effort to understand the social issues and effects of hydropower development in real-time.

Photographs can speak volumes that words cannot, and they can speak directly, increasing the voice of those who are not involved in the conversation. Reform and progress has everything to do with vision, with seeing ‘affectedness’ and ‘effects.’ Therefore, this work hopes to equitably shift the politics of seeing—by pulling the eye away from the centralized discourse of Kathmandu and toward the diverse assemblages of experiences, logics, agendas, aspirations, and understandings that exist in the interstices between master plans and ‘big people.’ While the presentation of this material cannot be truly objective, the critiques which emerge in this work are meant to be constructive: to describe the shifting formations and layered changes of the current moment; to support vigilance against abstraction and reduction; to describe what is happening and how it is happening, what is changing and for whom, who and what comes and goes, who benefits and who does not, how and why.

Further Reading

Adhikari J. & Hobley, M. (2011) ‘Everyone is leaving, who will sow our fields?: The Effects of Migration from Khotang District to the Gulf and Malaysia’. Kathmandu: Swiss Agency for Development & Cooperation (SDC).

Dixit, A., & Gyawali, D. (2010). Nepal’s Constructive Dialogue on Dams and Development. Water Alternatives, 3(2), 106-123.

Gidwani, V., & Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2003). Circular migration and the spaces of cultural assertion. Annals of the Association of American Geographers,93(1), 186-213.

Gyawali, D., & Dixit, A. (2001). Water and science: hydrological uncertainties, developmental aspirations and uningrained scientific culture. Futures, 33(8), 689-708.

Gyawali, D. (2001). Water in Nepal. Republished as ‘Rivers Technology & Society’ (2003). Himal Books.Hirsch, P. (2001). Globalisation, regionalisation and local voices: The Asian Development Bank and rescaled politics of environment in the Mekong region. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 22(3), 237-251.

Li, T. M. (2007). The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Duke University Press.

Pigg, S. L. (1992). Inventing social categories through place: Social representations and development in Nepal. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 34(3), 491-513.

Rai, K. (2008). The Dynamics of Social Inequality in the Kali Gandaki ‘A’Dam Project in Nepal: The Politics of Patronage. Hydro Nepal: Journal of Water, Energy and Environment, 1, 22-28

Rest, M. (2012) Generating power: debates on development around the NepaleseArun-3 hydropower project. Contemporary South Asi, 20(1), 105–11

Swyngedouw, E. (1999). Modernity and hybridity: nature, regeneracionismo, and the production of the Spanish waterscape, 1890–1930. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89(3), 443-465.

Edited by David Gonzalez.