SAGE Magazine is honored to award Hilary Faxon’s “Good evening, Dasho Benji!” second place in our 2014 Emerging Environmental Writers Contest.

Phobjikha Valley stands near Bhutan’s center, cold and wet at ten thousand feet. Steep slopes rise on all sides, and in monsoon season, catch the drifting clouds in clumps and trail them down through dense branches towards the wetland at the valley floor. The Kingdom of Bhutan is a series of ascending valleys, pockets in the Himalayas that, until one hundred years ago, were semi-autonomous, ruled by local penlops and connected through trade. Phobjikha is one of the highest valleys, just south of the border with Tibet. On its north ridge sits Gangtey Goempa, a Nyingma Buddhist school of monks and nuns and home to a revered tulku, a reincarnate lama. There are dormitories on the hill and one-room shops selling doma, a betel nut stimulant that stains teeth red. At the edge stands the goempa, a large, low, whitewashed structure with cracked frescos, carved wooden beams, and inscribed golden prayer wheels. Chanted prayers reverberate inside the large stone courtyard. The surrounding forest is filled with mosses and fogs and sister spirits who once stole the souls of the kings’ fastest messengers as they ran west from the old capital over Pele La pass.

Until recently the valley had no roads, so you had to travel from the goempa by foot to get into Phobjikha, following one finger of the snaking, splintering valley through wooded slopes and alpine meadows, past thick stands of dwarf bamboo and colorfully painted wooden houses. The drukpas, who grazed their yaks on the valley rim in winter, based their planting and harvesting cycles on the migrations of the Black-necked Crane, a massive black-and-white bird that winters in Phobjikha’s high-altitude wetlands. In the spring, after an elaborate mating ritual full of flapping and squawking, the cranes would cross the planet’s highest mountains to return to Tibet. Then, taking their cue from the avian migrants, or thrung-thrung, the people would come down to the valley to plant their crops.

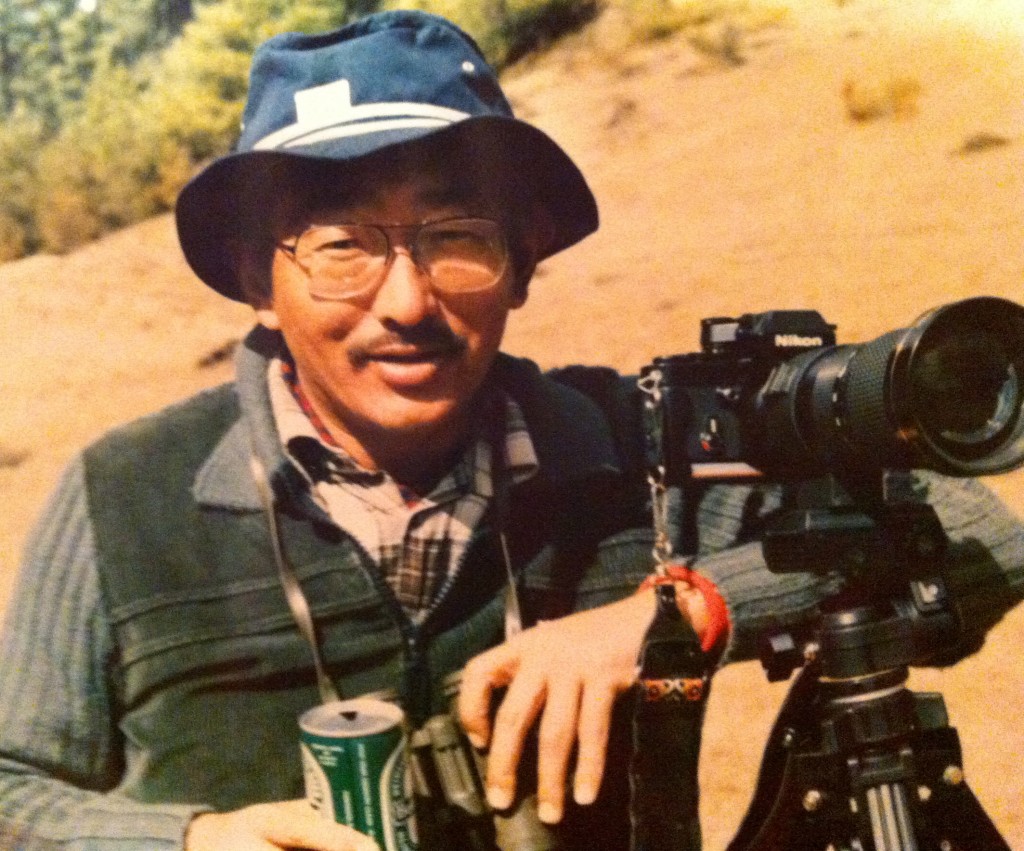

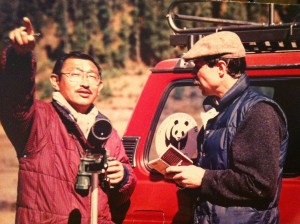

Dasho Benji loved those birds. As a 33-year old amateur naturalist in 1976, he had traveled to another remote valley in Bhutan’s far northeast with his younger cousin, the Fourth King. They arrived on December 18, the day after Bhutan’s National Day, and found the whole valley and sky teeming with large, low-flying Black-necked Cranes. His Majesty, also a nature-lover, netted two birds to keep in the palace aviary and joked that Benji could have the rest. Now, Benji thought, the cranes of Bhutan belong to me; I have to take care of them.

After that, Benji often visited Phobjikha to see his cranes. His son once told me about those boyhood trips. Over tea in his art gallery, he described Benji’s fascination with the mysterious, damp landscape and the rare birds that inhabited it. During the day, cranes are relatively sedentary, and pick at the wetland floor for grubs and scraps of food. But at dusk, they fly, circling the lower slopes in a whoosh and a flash of black and white. I can picture father and son on their pilgrimages to see the birds: prostrations and offerings made before the tulku; the descent in the red Land Cruiser, bouncing past the chorten, bamboo forests, yak herders and farm families in faded hand-woven clothing, eyes agape at a car from the capital.

Enter the potato. Phobjikha’s climate and soils were good for farming potatoes, or kewa, which had arrived from the Andes via India with Portuguese sailors in the 17th century. In the 1980s, Bhutanese policy and international agricultural specialists actively promoted potato expansion, and the hearty tuber quickly became a lucrative cash crop. The drukpas carried potatoes from Phobjikha’s valley floor to its rim, over the mountains and 100 miles south to the plains and markets of India. For Bhutan to develop, some argued, it would be necessary to drain Phobjikha; cultivation could only increase if the wetland at the valley floor were transformed into fields. Drying the wetland would increase potato production, but it would also destroy the home of Benji’s cranes.

Black-necked Cranes arrive in late October and depart by March. In Phobjikha winter, even the yaks seem to shiver. People drink suja, butter tea, or arra, rice wine, to stay warm. Travel would have been slow. When Benji arrived to survey the cranes, the valley floor was white with snow. He counted over eighty birds, and returned home to report to His Majesty, and beg him to help protect the fantastic cranes. Phobjikha was never drained. Every winter since, the thrung-thrung have come.

Dasho Benji once told me the story of meeting the first President Bush in Rio at the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit. Today “Rio” is embedded in modern environmentalist mythology, but then it was just another intricate international pow-wow for the sophomore drukpa delegation. Benji was invited to a luncheon for founders of non-governmental organizations; five years earlier he had created Bhutan’s first environmental group, the Royal Society for Protection of Nature, to promote environmental education and protect the Black-necked Cranes.

Benji sat at the table to eat. Jacques Cousteau gave opening remarks. As the meal progressed, Bush requested each invitee make a short speech. The guests stood one by one, discussing their work and expressing gratitude to the American President. When it was Benji’s turn, he rose and stated that his esteemed colleagues had already elaborated on all the important points. He mentioned that tiny Bhutan strove to think globally and act locally. Then he turned to Bush. “But, since you asked me Mr. President,” he began, and proceeded to say that all the world’s money aimed at stemming poverty and conserving the environment would go into a bottomless barrel until development powers confronted the controversial problem of population growth. He remembered the look on Bush’s face: it said, “Who the hell is this guy?”

“Say what you will about me,” he told me twenty years later, “but Benji never took no shit from nobody.”

As a boy, Dasho Benji was brought up on comics. He especially loved the devious villains and heretical heroes of Zane Grey’s Wild Wild West. He describes his boyhood self as a troublemaker. It was that mischievous energy that led him to join the Natural History Society when he was at boarding school in Darjeeling, India. “One day they came to class and said, ‘Anyone who wants to be in the Natural History Society put your hands up!’ Well, all the rascals put their hands up,” Benji remembered. The Natural History Society met outdoors on Saturdays, and the boys were eager to get out of chores and classrooms. And so it began – Benji learned about ecology and ornithology, often skipping tea to stay outside and count more birds. He brought his love of animals and plants back to Bhutan. His passion flourished in the lowland sanctuary on Bhutan’s southwest border and then in the mountains and rivers around the capital, Thimphu. He may have been a birdwatcher and a Buddhist, but all those childhood cowboy novels had sunk in: when he met the Texan he was ready for the rodeo.

I first met Lyonpo Paljor J. Dorji in the squat wooden offices of the National Environmental Commission, right behind the royal dzong. “Never call me ‘sir,’ Hilary,” he said, “call me Benji.” Bhutan’s culture is formal and hierarchical, so Benji’s immediate warmth and openness surprised me. I was a junior researcher, five months into my work at the Royal Society for Protection of Nature; an outsider attracted to the kingdom’s sterling environmental record, alternative development model, and mountain climbing. He was a Lyonpo, an honorific title granted by His Majesty for service to the kingdom, and the godfather of national conservation. I came to interview him about a Society project documenting its twenty-five year history. I asked the first question, and Benji went off for an hour. By the end of our interview, I was decoding his old Word Perfect files. I was rewarded with memos, diaries, and letters that documented Bhutan’s early conservation movement — and Benji’s friendship.

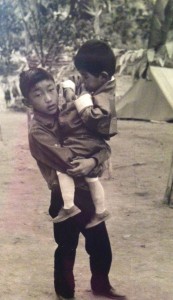

As a boy, Benji was selected as a companion for the heir apparent. The boys grew up in the 1960s as Bhutan made its leap into the modern world by building its first roads, schools, and hospitals. At 17, Benji’s newly crowned cousin coined the term “Gross National Happiness,” a development model that promotes balanced consideration of social, political, ecological, and environmental factors. GNH stands in contrast to traditional metrics such as GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, which places value solely on economic activity as a proxy for wellbeing. The policy would make Bhutan famous among development wonks, attracting chilips, or foreigners, such as myself to study the secrets of sustainable happiness.

Benji sometimes calls himself the King’s “court jester.” With my Western education, I think of King Lear’s Fool, the only character able to speak truth to the monarch. But more endemic is the Mahayana Buddhist veneration of crazy-wisdom. In Bhutan, this quality is personified in the saint and national hero, Drukpa Kinley, also known as the Divine Madman. Drukpa Kinley is known for his startling irreverence. He criticized the rigid methods of monastic institutions and preferred instead to help his pupils achieve enlightenment through poetry, wine, and sex. He writes that this seeming contradiction between outer behavior and inner holiness is in fact all bound in the reality of a genuine yogi. His unconventional approach comes not from disrespect for Buddhist teachings, but rather from an attempt to translate his hallowed understanding to the vernacular. The Divine Madman may seem an impulsive fool, or the life of the party, but he is in fact working in his wisdom for the benefit of all beings, acting simultaneously as holy teacher, true believer, and troublemaker.

Like Drukpa Kinley, Dasho Benji has taken many forms to promote his ideals: court jester, Chief Justice, Ambassador to Geneva, Minister of the National Environmental Commission, and tour guide to Mick Jagger and Leonardo DiCaprio. His convictions and methods are often unorthodox. Consider, for example, his old habit of collecting foreign donations of uniforms and scientific equipment for the fledgling forestry department, then chucking the boxes over the runway fence back home to avoid customs hassles; or his idea for the Bhutan Trust Fund for Environmental Conservation.

Benji told me that when he first presented a plan to the Royal Cabinet to raise $20 million to finance ongoing conservation projects, they nearly laughed him out of the room. Benji persisted, explaining the importance of protecting against donor fatigue. At the time, the early 1990s, Bhutan had just bought its first airplane. “Is our environment cheaper than little bloody airplanes?” Benji asked. The next year, he secured an initial pledge from the World Wildlife Fund. Okay, maybe you could raise two million, five if you’re lucky, the Cabinet conceded. Benji didn’t back down. Finally, the King set the formal goal at ten, with a soft target of $20 million.

Benji returned to Europe as a diplomat, wielding his charm to garner support. He met with donors, technocrats, ministers, and kings. He convinced one recalcitrant country to donate to the Fund as an “upstream investment” for their historic aid partner, Bangladesh. (“In desperation I threw the Bangladesh line and his whole attitude changed,” he wrote in his notes). At the close of the first Cabinet meeting, one of the ministers joked he would buy Benji a Mercedes if he succeeded in raising ten million. By rights, Benji should have a couple of fast cars by now. Today the Fund reports an investment portfolio upwards of $44 million and has approved 130 grants for domestic environment projects.

When Benji returned from Europe, he set to work helping draft Bhutan’s first National Environmental Strategy. The document, published in 1998, was titled “The Middle Path” in reference to the Buddhist idea of choosing the most balanced, moderate way forward. It formalized Bhutanese commitment to conservation, and set the stage for progressive legislation, including a constitutional commitment to maintain 60% forest cover (the current stat is an extraordinary 72%) and a national park system that covers just over half the nation’s land area. “Environmental Conservation” is now one of the four pillars of Gross National Happiness, and environmental ethics are celebrated as part of national identity.

In a personal memo from the drafting period, Benji spelled out the guiding principals of a Buddhist conservation ethic. We read it together over yak burgers at The Zone, a popular hangout and karaoke bar. Environmental strategy must begin with Right Mindfulness, a Buddhist tenet that states one should first look inward and cultivate proper thought patterns before addressing external concerns. “Environmentalism,” Benji wrote, “will not come from policy or legislation, but from individuals who are taught the ‘why’ of conservation, not just the ‘how.’”

Benji’s cheek has earned him affection from an unlikely source. “Oh, the Dalai Lama loves Dad,” Benji’s son tells me, after his father relates an enthusiastic reunion at an international conference. The two men share geographic origins, a passion for advocacy, quick intellect and a fascination with modern science. Still, they are an odd match. One imagines that certain aspects of Benji’s history – brushes with Christianity, Drukpa Kineley-esque tendencies towards booze and women, a general swagger – might irk His Holiness. Not so. “This story is called, ‘Benji and the Dalai Lama!’” Benji proclaims.

Once upon a time Benji was on official business in a big Indian city, doubling as a security guard for His Majesty, and discovered the Tibetan spiritual leader was staying just down the road. He hurried over to pay his respects, wearing his traditional gho – a wrapped tunic with a massive, open, front pocket. His Holiness was seated before the altar, surrounded by his guards. As is customary when approaching the sacred, Benji greeted the Dalai Lama with three full-body prostrations. He raised his hands, dropped to his knees, and spilled his torso on the floor to touch his forehead to the ground in the ultimate gesture of humble devotion. On his first prostration, Benji’s gun came flying out of his gho. The Dalai Lama’s security squad leapt into action, but His Holiness motioned for them to stop. Red-faced but undeterred, Benji persevered through another prostration. As he bent, six bullets rattled across the floor. Again security jumped to seize him, and again His Holiness raised a hand. But as Benji launched into his final round, the Dalai Lama cut him off: “Benjo-la, something more?”

Quiet Bhutan is growing up, into an era of pizza delivery and democracy. The 2013 general election, the nation’s second, featured a peaceful transition of power amid ugly mud-slinging Tweets. Constituents demanded roads, and candidates promised them. Roads bring markets, medicine, and education, but also leave scars on landscapes, fragment habitats, spur erosion, and open up new territory for poachers. The streets of Thimphu are strewn with waste and lined with open sewers. These increasingly operate above capacity as rural migrants stream into the city. Meanwhile, all across the world’s “third pole,” glaciers are melting from above, and being dammed for hydropower from below.

And the ineffable Benji is growing old. In September 2013, we went out to Phobjikha. We camped on the valley floor, on grounds where cranes would soon walk, which could have been stuffed with pesticides and potato. Benji woke early each morning to wash his face to the chanting of monks, and he stayed up late in the evening to entertain foreign ecologists around the bonfire. He took us up the goempa to meet the tulku, conducting our rag-tag gang with characteristic enthusiasm. When pouring rain forced us to huddle underneath a sagging tent, he channeled Drukpa Kinley, bringing out the whiskey and leading a rousing (and perhaps improvised) chorus: “We’re off to see the Thimphu zoo / the elephant and the kangaroo! / Never mind the weather, as long as we’re together! / We’re off to see the Thimphu zoo!”

He also napped more. And was more forgetful.

Many young Bhutanese environmentalists can thank Benji for their jobs today, and the Black-necked Cranes can thank him for a new generation of protectors. And Benji keeps going, organizing a symposium to showcase environmental scholarship, appearing on televised debates about road construction, and broadcasting his very own radio show – Good Evening, Dasho Benji! – every Monday at 5. Still, that doesn’t mean that Bhutanese always want to listen. “All my young colleagues, they’re smart, smarter than I, with good minds, but they have to be pushed, nudged,” Benji once told me. A new era demands new tactics: the personal persuasion of an absolute monarch is out; more nuanced strategies, including good-natured mass Facebook shaming, are in. When the first meeting of his new Ecological Society had to be postponed because attendees canceled last minute, Benji posted on the Facebook wall of his group, Bhutan Nature Cares: “Everybody toooo busy with their various duties and responsibilities! Miss the good old days when I said “DO” and it was “DONE” Hahahahahahaha!”