A Media Firestorm

On January 27, a Turkish reporter for the Dogan News Agency wrote about Turkey’s low ranking in the 2016 Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI). Two days later, Dogan News published “Turkey on the Bottom,” an exposé bemoaning Turkey’s “retrogressive decade” of environmental performance that pushed the country’s Climate & Energy and Biodiversity & Habitat index scores below those of Iraq, Syria, Libya and Haiti. Within hours, the article was shared thousands of times on Facebook. It drew a swift rebuke from Turkey’s hardline government supporters and ignited a media firestorm that produced scores of articles.

In a hastily crafted, 700-word rebuttal entitled “Yale’s Lies,” Turkey’s Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs excoriated the 2016 EPI for its “slanderous… defamation” of Turkey’s “world-leading reforestation and nature conservation.” What followed was a long enumeration of government statistics about the purported health of endangered species – evidence, the Ministry’s leaders claim, that the EPI failed to accurately reflect “the reality on the ground.”

Most of the government’s prominent mouthpieces in the media – Milliyet, Vatan, Yeni Asya – ran the same story, while others like Cihan and Haberler gathered information from the Ministry’s General Directorate that described EPI’s Biodiversity & Habitat data as “untenable,” “unfounded,” “misleading,” “unreliable,” “open to debate,” and “in need of explanation.” Several media sources questioned the messages amplified in this echo chamber, despite the risks that dissenting journalists face under Erdoğan’s presidency.

The Greens and the Left Party of the Future’s newspaper, Yeşil Gazete, used Turkey’s poor EPI showing to criticize President Erdoğan’s environmental record. After describing Turkey’s “rapidly deteriorating environmental performance” and stressing the reliability of EPI’s data sources, they lobbed one of President Erdoğan’s frequent aspersions of their party back at him, calling Turkey a “Çevrecinin daniskası,” which means “idle environmentalist,” or “green’s a joke.”

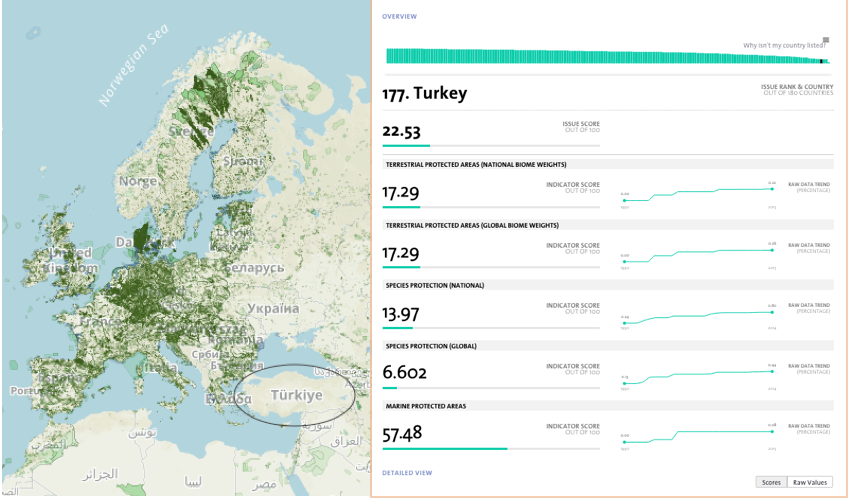

Zaman, Turkey’s most widely circulated and recently censored newspaper, blamed some of the country’s environmental struggles on deliberate actions that undermined the Wetland’s Protection Ordinance, the “only legal obstacle” to restrict further habitat destruction. Many wetland species are pushed to the brink of extinction, which in part explains Turkey’s Biodiversity & Habitat low rank in the 2016 EPI (177 out of 180). Meanwhile, Erdin Bircan, one of The People’s Republican Party’s environmental ministers was unequivocally critical of the government, stating “the damage [the ruling AKP government] cause[s] to the environment was revealed by Yale.”

***

The State of Turkey’s Environment

The 2016 EPI reveals that Turkey’s performance on the EPI’s Biodiversity & Habitat indicators fell by 23.42% in the past decade – a trend that Bircan said is attributable to “13 years of AKP rule.” He cites information from a piece written by a Yale EPI 2015 summer intern, Fatima Bishtawi. Ms. Bishtawi’s research found that roughly 5% of Turkey’s territory is under official protection, yet less than one quarter of these areas are actually enforced. New construction has destroyed some 1.3 million hectares of Turkey’s wetlands and 87% of its peatlands, a calamitous outcome for a country home to 10,000 plant species and 80,000 animal species, many of which are endemic.

Turkey finished twelve spots away from the worst performing country on the 2016 EPI’s Climate & Energy indicators. Ms. Bishtawi’s research uncovered national legislation that will only catalyze the destruction, including laws that classify forests as “not forests” and the merger of the environmental ministry with its dam-building agency, Devlet Su İşler.

Meanwhile, public support for environmental protection in Turkey, which ignited the 2011 Gezi Park protests, has waned; only 0.3% of Turks said that they felt that environmental issues were among the nation’s greatest problems last year. Turkish citizens are more concerned with terrorism and refugees, who now flock to Turkey from its war-torn neighbors.

***

An Unexpected Visit

While these humanitarian crises have captured a large portion of Turkey’s resources and political capital, the Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs was steadfast in its desire to get answers from the EPI. Its Deputy Minister, Professor Lutfi Akca, visited Yale’s campus just days after the media storm broke. Minister Akca was here to sign an memorandum of understanding with Yale Professor Chad Oliver’s research group, the Global Institute of Sustainable Forestry, but he also requested to meet with the EPI team. With two hours’ notice, I met the Turkish Minister in Yale’s Kroon Hall, alone, after Professor Oliver assured me that the minister “was not here to pound his fists on the table.”

Minister Akca wanted to understand EPI’s methodology, data sources, and to learn about the report’s scientific rigor. I explained to him that, while Turkey had performed poorly on our Biodiversity and Climate indicators, the country’s overall rank (99) placed it firmly in the middle of global environmental performance. Indeed, our back-casted data shows that Turkey has actually improved its overall score on the 2016 EPI’s set of indicators by 7.3%. The most significant factors contributing to this improvement are Turkey’s enhanced air quality, water resources, and its fisheries, which all saw score increases of 20% to 45% in the last decade.

We talked at length about what our Biodiversity & Habitat indicators do and do not explicitly measure. While securing protected areas is a good first step, they do not ensure conservation. We note in our metadata that, “[h]ow well protected areas are managed, the strength of the legal protections extended to them, and the actual outcomes on the ground are all vital elements of a comprehensive assessment of effective conservation,” for which global metrics are still under development. This is where Turkey has struggled.

He asked how we gather air quality data (from satellite estimates) and why we avoid governmental data like the particulate matter 10, or PM10, air quality readings he reports to the Eurasian Economic Union (to circumvent false reporting and obtain global information about difficult to monitor issues like small particulate matter, PM2.5, the air quality pollutant more relevant to human health). We discussed EPI’s methodologies for weighting indicators before aggregating category scores into a summary score for each country, and I informed him that all our data is publicly available on our website along with metadata, a transparent feature that he clearly appreciated. I also explained that more than 70 experts contributed to the 2016 EPI, and he congratulated our team on a “fine report” that we should be proud of. We parted with a friendly handshake, agreeing to remain in touch as he reported back to his superiors.

***

A New Crisis

Minister Acka encountered tensions spilling over anew upon his return to Turkey. In Artvin, a mining company, Cengiz Holding, defiantly restarted construction on a gold mine – this time under protection of hired guards and police. Characterized by President Erdoğan as a “junior Gezi,” thousands of protestors are now “fighting for their way of life” through clouds of tear gas, plastic bullets, and roadblocks in a last-ditch effort to save 50,000 trees. Once again, environmental issues dominate Turkish headlines, and reporters are countering governmental claims with EPI results. While the ultimate outcome of these protests remains uncertain, environmental issues are igniting political skirmishes in Turkey, proof that revealing data can strike fear into a country’s leaders and empower its critics.