SAGE Magazine is thrilled to award Ari Phillips’ “The Water Generation Gap” honorable mention in our 2013 Environmental Writing Contest.

Water flows uphill towards money.

-Common saying in the American West

The frog does not drink up the pond in which he lives.

-American Indian saying

Just outside of Utopia, Texas, about 80 miles northwest of San Antonio, is a massive 40-foot wide sinkhole that can transport up to 1,770 gallons of water per second into an underground aquifer. On a warm winter day, I stood with Sharlene Leurig near the edge of the sinkhole, imagining water whirlpooling into the inner cavity of the dark limestone abyss after a big rainstorm. The closest we got to that primeval image of foamy whitewash rushing deep into the earth, however, was a video on a cellphone that another observer shared with us. The sinkhole, known as Seco Sinkhole, was bone dry, and was likely to remain so for quite some time. As Texas enters its third consecutive year of drought with above average temperatures, parched summers, strained reservoirs and harsh water restrictions, the record-breaking heat and drought of 2011 may become the new normal for a state accustomed to an ample water supply.

Leurig, a 32-year-old native Texan recently returned from the Northeast, had on bulky boots – the wrong footwear with which to keep one’s balance – and hesitated to approach the sinkhole’s ledge. Instead she busied herself taking pictures with the digital camera she’d bought the day before. She has shoulder-length brown hair, deep-set eyes, and an inviting smile. As a manager at Ceres, an advocacy group that represents long-term investments horizons, Leurig works with water service providers to help them understand how trends like climate change and water scarcity will affect the value of their investments.

“I’m amazed when I talk to people who’ve lived in Texas their whole life and they don’t know about the springs,” said Leurig as we made our way to the other side of the sinkhole, where we met two employees of the San Antonio Water System, or SAWS, who’d come along for an off-the-beaten-path excursion. The idea for the trip had been Leurig’s, who writes a personal blog documenting the state’s springs.“At its most fundamental, the blog is just meant to help people find springs that are pretty, or where they can go swimming,” Leurig said. “But that at the same time might actually inform them without them knowing they’re being informed. Information like where the water comes from and what sort of things are happening that might affect that water being there in the future.”

Seco Sinkhole feeds into the Edwards Aquifer, a subterranean layer of porous, water-bearing rock 300 to 700 feet thick that sits beneath Central Texas, and in many ways, defines it. The sinkhole is an entryway into a sprawling underground storage facility that supplies water for over two million people. It’s part of the 1,250 square-mile area recharge zone where faulted and fractured limestone penetrates the land’s surface and allows large amounts of water to enter the aquifer.

From the aquifer flow the area’s countless freshwater springs, along which human settlement – from Native Americans to Spanish missionaries to German immigrants – has occurred for thousands of years. Like many of the freshwater springs across Texas, the aquifer is literally what gave rise to civilization in this corner of the world. It provides water for Austin’s treasured Barton Springs and much of the available irrigation for farmers and ranchers. It also supports seven endangered species, including the Texas Blind Salamander, a type of wild rice, and two beetles. However, over the last generation, water has become an increasingly scarce commodity in Texas and across much of the western United States.

***

As climate patterns shift and populations continue to grow and urbanize, global thirst for water will soon be unquenchable. For some places, like North Africa and Australia, that point has already been reached. In Texas, a perfect storm is brewing as the population booms and water resources deplete. Many people believe water will soon overtake oil as the next major resource in the state. Already, investors are making sustained efforts to secure water assets and rights. At the same time, Texans continue to overuse water for lush lawns, poorly suited agriculture, and overtaxed infrastructure without considering the long-term impacts of these habits.

“If people understand how rich this state is in springs, and how those springs provide most of the flow for many of our rivers, then maybe they’ll pay more attention to how they’re depleting them,” Leurig said as we left the sinkhole to return to our car. “Right now we’re at this really critical moment because of all the money that could be pumped into new water supply projects. A lot of people in the state, many whom come from oil and gas money, view water as the next big resource.”

As recently as a generation ago, most Texans either relied on rain for survival – for livestock or agriculture – or knew a family member that did. That connection to water has been all but lost over the last 50 years as reservoirs have brought a reliable water to an increasingly urbanized population.

But it’s becoming apparent that in many ways, water equals money. If Texas wants to keep attracting new business, it will have to provide sufficient water. This fact has lawmakers, wary of allocating money to big government projects, engaged in an earnest discussion about how to spend money on water to keep companies engaged in everything from fracking to food production happy. The state is also caught up in legal battles over water with neighboring New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Mexico. Meanwhile harsh water restrictions are being put in place from Midland, the heart of the current oil boom, to San Antonio.

More than half of the usable freshwater in Texas comes from groundwater. It is used for domestic, municipal, industrial, and agricultural purposes with nearly 55 percent of Texans relying on groundwater for their drinking water. There are 23 aquifers across Texas underlying about three-quarters of the state. Groundwater is regulated differently in Texas than surface water. It is treated as a private good that is owned by whomever owns the land above it, whereas surface water is a public good owned and managed by the state. Springs are where the two sources converge. They act as a reminder that even though groundwater and surface water are legally separate, the future of water availability in the state relies just as heavily on maintaining groundwater supplies as it does managing surface water flows.

“All sorts of groundwater projects are getting proposed because groundwater is treated as private property,” Leurig said as we drove back towards San Antonio. “There’s no limit on what you can do with groundwater really, and projects can often get permitted with basically no resistance. Especially in West Texas, where some of the most precious springs are.”

I first met Leurig at the 2012 Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Lubbock, where she spoke about water sustainability from a business perspective. She’d warned about the challenges of water management in the West, particularly regarding the water under our feet, the southern portion of the vast Ogallala aquifer. One of the largest aquifers in the world, the Ogallala yields about 30 percent of all groundwater used for irrigation in the United States.

Depletion of the Ogallala aquifer is most severe in Texas, where it doubled in the first decade of the 21st century compared to the previous fifty years.A 2011 USGS study found that 29 percent of the Texas portion of the Ogallala had already been depleted, and in some areas, levels have declined up to 150 feet. To some it seemed like institutionalized depletion of a resource that took tens of thousands of years to fill during the last ice age. At the conference, many spoke about the “50/50 Management Goal” – ensuring that at least 50 percent of the Ogallala groundwater will remain in 50 years.

On our way back from the sinkhole Leurig and I stopped at Gregg Eckhardt’s house, the Senior Analyst for the San Antonio Water System’s Treatment Group, which manages wastewater in the city.. He lives in a ranch-style house just outside San Antonio, in front of a well-manicured yard full of natural vegetation. Eckhardt is small in stature, with graying hair and glasses. Although he may appear subdued, he is a force to be reckoned with when it comes to water issues in Texas, especially issues relating to the Edwards Aquifer. His website, , a side project of his for nearly 20 years, has grown into the default resource for many Edwards Aquifer issues, much to the chagrin of the Edwards Aquifer Authority, whose website comes up second after Eckhardt’s when you Google “Edwards Aquifer.”

Eckhardt showed us his copy of Springs of Texas: Volume I, a tome of a book that only true springs aficionados possess. Self-published in 1981 by Gunnar Brune, a geologist who spent years documenting springs across the state and writing about their historical and cultural significance, it was long out of print until another Texas water lover, Helen Besse, took it upon herself to have it reprinted by Texas A&M University Press in 2002.

“In 1718, Spanish Missionaries founded San Antonio on the banks of San Pedro Creek, just below the springs,” Eckhardt said while flipping through the book. “These springs and headwaters have been used by humans for more than 12,000 years. But more than that, they have prehistoric significance. The bones of mastodons, giant tigers, and extinct horses have been found here.”

***

A week after the San Antonio trip I met Helen Besse (responsible for the reprint of Springs of Texas: Volume I) in the University Christian Church on the University of Texas campus in a stuffy, over-decorated conference room. She was full of energy, and enthusiastically jumped from one topic to another.

“I had a contract from the Texas Water Development Board to find new springs in the 71 counties not covered in Volume I,” Besse said. “I found over 700 springs, but had to cancel the contract eventually because landowners didn’t want to share the locations of their springs with the state. So now I just have all this data.”

Recently retired from a long career as an environmental consultant, Besse became interested in springs for the same reason as many people in Austin: she was enchanted by Barton Springs, Austin’s own outflow from the Edward’s Aquifer. Barton Springs Pool a man-made recreational swimming pool fed by groundwater, is the soul of Austin. When summer comes with its consecutive days of scorching, humid heat sweaty Austinites head for the banks of the pool like drops of water following a natural watershed.

“I used to swim in Barton Springs daily; I found them very spiritual,” Besse said. “That’s when I got really involved in water issues. Now I don’t ever turn the water on and walk away. I’m extreme. I’m awful.”

Besse also attributes her concern with water to the intense drought, similar to the current one crippling the state, that she experienced as child. “I grew up in the 1950s in South Texas during a major drought,” Besse said. “My mother bathed my brother and I in a washtub rather than a bathtub because it didn’t use as much water. And I’ve never been comfortable taking a bath. Who wants to bathe in that much water? So water conservation is in my cells.”

Besse firmly believes that a historical understanding of springs could help today’s youth redefine their relationship with water. This historical perspective is part of why she so admired Brune’s Springs of Texas, for which she wrote the reprinted introduction. “Brune shows the Spanish expeditions that came through Texas. Indians knew where the springs were and they knew how to get around. There are stories about Spaniards learning spring locations from Indians,” Besse said. “Once that knowledge was lost people trying to get through the desert would die. Then eventually the settlers came and settled around springs.”

She thinks one good way to raise awareness would be to create a Texas Springs Trail much like the Texas Birding Trail, Texas Forts Trail, and recently established Texas Kayaking Trail. This would enable people out on weekend excursions to stop for a brief moment at any number of public springs across the state and maybe even at some private ones, if the owners agreed.

“Water is an endangered resource now, and I think at some point it’s going to overtake oil in Texas as the big important thing,” Besse said, growing serious. “Already there are companies from other countries coming in and buying up water rights, and some of our favorite elected officials in Texas encourage their relatives to do the same. If I was a doomsday kind of person and wanted to make a movie about what was really going to happen to the world, it would be about water – I hope in my heart of hearts that doesn’t happen.”

***

Both Besse and Leurig insisted that I meet Andrew Sansom, executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University-San Marcos and former executive director of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. So a few days after meeting Besse, I drove down to San Marcos, midway between Austin and San Antonio along I-35.

“We held an international water conference here in the middle of the 2011 drought,” Sansom told me during our meeting in this office. “I had just finished telling people about the historic drought we were experiencing when a lady from Malawi approached me and said, ‘Our drought started in 1976.’ So the scary thing to me is that we just have this presumption that all these episodes are going to be temporal, but the fact is that this could go on for 100 years.”

The Meadows Center is located at the headwaters of the San Marcos River, where the Edwards Aquifer-fed San Marcos Springs bubble and burst from three main fissures and a number of other openings. It is widely believed that the area around the San Marcos Springs, which is one of the biggest outflows of the aquifer, is one of the oldest continually inhabited sites in North America, with archeological evidence showing humans inhabiting the site for up to 11,500 years.

William A. McClintock’s Journal of a Trip through Texas and Northern Mexico in 1846-1847 provides a vivid description of the scene former inhabitants witnessed:

… A mountain torrent of purest water, narrow and deep, there is the finest spring of springs I ever beheld. These springs gush from the foot of a high cliff and boil up as from a well in the middle of the channel. One of these, the first you see in going up the stream, is near the center, the channel is here 40 yds. wide, the water 15 or 20 feet deep, yet so strong is the ebulition of the spring, that the water is thrown two or three feet above the surface of the stream. I am told that by approaching it in canoe, you may see down in the chasm from whence the water issues. Large stones are thrown up, as you’ve seen grains of sand in small springs, it is unaffected by the dryest season…

Great numbers of the finest fish; and occasionally an alligator may be seen sporting in its crystal waters… In the eddies of the stream, water cresses and palmettoes grow to a gigantic size.

About 100 years later, starting in 1951, the springs became the location of Texas’s most popular amusement park, Aquarena Springs. The theme park included mermaid performers, a sky-ride gondola, Ralph the Famous Swimming Pig who did tricks such as the “swine dive,” and the main attraction – a submersible underwater theatre.

“It would be considered pretty funky by today’s standards,” said Sansom, “but in the forties, fifties and sixties everybody came.” We were talking in his corner office in the newly restored Meadows Center, originally built in 1929 as the Aquarena Springs Hotel. As he spoke I looked with envy at the splendid view of the dammed San Marcos River just outside the window. The only structure remaining from the amusement park era, the two-story building is over 200-feet long and has an ocean-side feel, with concrete bannisters along the lakeside, large viewing windows, and second-story balconies. Sansom’s office is located in the former Honeymoon Suite.

When I entered his office he’d been checking the forecast, no doubt following the current storm pushing through the region, hoping (or perhaps praying) for rain. A self-avowed weather fanatic, he believes weather patterns in the region are changing due to climate change and that the Hill Country is getting more arid, with hotter days and cooler nights, as the desert climate to the west pushes eastward.

“My mantra is that we can’t build our way out of this,” Sansom said. “It doesn’t matter how many reservoirs or pipelines or water treatment plants we build; if we convert all of our watersheds to parking lots or feedlots, we’re toast. So there’s just a list to me of non-infrastructure issues that we don’t seem to be willing to address at all.”

By ‘we,’ Sansom meant Texas politicians and other bureaucrats, and by ‘building our way out of this’ he was referring to the Texas State Water Plan, a cumbersome 250-page document that would take around $50 billion dollars to fully fund. Water is a top priority in the 2013 legislative, with all branches of government promoting new revenue streams to help locate new sources of water and shore up old ones, often through large infrastructure projects.

“Here we are saying all we need to do is get a billion dollars from the Rainy Day Fund and everything will be OK. Well, that’s BS,” Sansom said. “We have a state where all of our watersheds, all of our recharge areas, all of the things that make the hydrologic cycle work are on private property because we’re a state that’s owned by private citizens – yet we do absolutely nothing to protect those watersheds.”

Sansom tossed off an analogy that summed up the convoluted issue of groundwater versus surface water in Texas. “We manage water in Texas as if when it’s in the river it’s chocolate but when it’s in the ground it’s strawberry, and that’s not sustainable,” he said. “Sooner or later that’s going to come home to roost and we’re going to have a really serious problem.”

***

In Texas, surface water belongs to the state, and requires a permit to use, but groundwater belongs to the owner of the land above it and may be used or sold. Derived from the English common law rule of “absolute ownership,” this is known as the rule of capture, or more descriptively, “the law of the biggest pump.” Texas courts have consistently ruled that a landowner has a right to pump as much water as he wants from wells on his land regardless of the effect on adjacent landowners’ water tables.

The Texas Supreme Court originally adopted the rule of capture in 1904. In the intervening century much has been learned about the hydrologic cycle, including the limited availability of groundwater and its interconnection with surface water. Add this to the fact that much of Texas gets relatively little precipitation – on par with the rest of the West where rule of capture isn’t used – and the logic of Texas’ water laws gets even murkier.

This distinction is particularly tenuous in the Central Texas Hill Country. Last year’s high-profile Day vs. Edwards Aquifer Authority case – in which the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the Edwards Aquifer Authority owed landowners monetary compensation for limiting the amount of groundwater they could use – is widely seen as an indication of the battles to come and the growing recognition of the importance of water in the state.

In deciding that water is the property of landowners, the court relied on an established Texas legal framework that considers groundwater resources in the same way as the state’s oil, gas, and mineral deposits. In the decision, the Court even gave a nod to the increasingly common view that water is, in terms of importance, the new oil:

To differentiate between groundwater and oil and gas in terms of importance to modern life would be difficult. Drinking water is essential for life, but fuel for heat and power, at least in this society, is also indispensable.

The issue is not whether there are important differences between groundwater and hydrocarbons; there certainly are. But we see no basis in these differences to conclude that the common law allows ownership of oil and gas in place but not groundwater.

To get a first-person account of groundwater issues, I visited David Langford, retired CEO of the Texas Wildlife Association, professional wildlife photographer, and seventh-generation Hill Country resident, on his parcel of his family’s original 13,000-acre ranch near Fredericksburg, located at the northwest point of an equilateral triangle with Austin and San Antonio.

Langford surprised me with a different perspective. “Rule of capture went away 15 years ago when they formed groundwater districts,” Langford, an imposing figure with no use for minced words, said. “Now, with only some exceptions, you need a permit to use groundwater, especially in places where anybody is worried about wasting it. So the rule of capture is an old wives’ tale that doesn’t exist anymore.”

According to Langford, the level of regulation in a groundwater district depends on the locally-elected board, which can range from people interested in best practices to water-crazed developers. Langford cites Kimble County, where he lives, as a well-managed district where the board members know the laws, administer them with an even hand, and defend everyone’s groundwater rights, “whether you’re a terminal patient in a hospital or somebody who wants to sell water to Ozarka to put in those little bottles.”

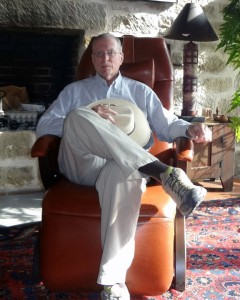

Langford is tall, with a pinched nose, narrow mouth, and combed-over gray hair covered by a white Stetson cowboy hat. He moves with the practiced ease and steady gait of someone whois used to surveying land. His great-grandfather, Albert Giles, a well-known architect, founded the ranch in 1885 that Langford still surveys.

“The family takes great pride in being good stewards of all resources, whether that is livestock, wildlife, plants, pets, or grandchildren or grandparents,” Langford said sitting in front of a fireplace built into the limestone wall in the living room of his modestly-sized farmhouse. “One of the things we take great pride in stewarding is water.”

The water on the Langford’s property is all groundwater, with the creeks being spring-fed. The ranch is part of the Guadalupe River watershed, and rain on the property eventually flows all the way down to the coastal bays and estuaries where endangered whooping cranes stopover during their yearly migration. Langford pronounces “whooping” with a strong “w” followed by a forceful exhale on the “h”, making the birds seem somehow more exotic.

“Our reward for these efforts is that developers build subdivisions and people sprinkle St. Augustine Grass and wash their driveways down when their poodle gets muddy footprints on it,” Langford said with pronounced disdain. “There’s a tropical rainforest grass growing in people’s yards. If they’re going to take all the water beneath the ranch to keep people alive in hospitals, that’s OK. But if they’re going to use it to overwater grass, that’s not OK.”

He shifted to a more amenable tone, as if just remembering I was in the room. “Twenty years ago we weren’t having this conversation,” he said. “If you wanted to use water you turned on the damn pump, ‘cause there was plenty of it. But things are different now. And if someone moved out here understanding there was enough water to irrigate crops so they can send their kids to school, how can you be mad at them? There’s no way anyone, especially anyone in my family, is going to say, ‘No, you can’t have your American dream.’”

We left the comfort of his home and headed out the back door, walking about 50 yards to the nearby spring and then another 25 yards to the well. As we meandered through live oaks and along various limestone outcroppings, he explained the extent of the worsening groundwater situation.

“From 1963, when the well was drilled, to 2000, the water level remained about 125 feet below the surface. Now the well is down over 60 feet, and it didn’t come up during all the rains last spring.”

The spring was a trickle about ten feet up from the bank of the small creek, itself not much more than a trickle. Encased in a limestone structure, like a primitive hot tub, the spring was covered by a piece of sheet metal. Langford said when there’s a lot of rain the tub fills up.

According to Langford, this part of the aquifer recharges about five to seven percent a year. With average rainfall about 30 inches per year, the most recharge he can expect in any given year is two inches. Instead, it’s been falling about five inches a year. The well taps out at 250 feet, a level that could be reached in a decade.

If you really want to make yourself ill, do the math,” Langford said as we gazed out over an open pasture of natural grasses and a few scattered trees above the spring. “For that well to do back what it was doing in 2000 it has to rain twice the average rainfall every year for 26 years.”

What differentiates Langford from many other water users is that he thinks long-term. His family has been on the same ranch for six generations and he’d like them to be there for at least six more. He could have sold the property long ago, and it would have been neatly subdivided by now.

“I lived in San Antonio for a long time,” Langford said as he walked me to my car. “You go to a cocktail party and the subject of water comes up and people don’t have a clue. They say things like, ‘Wasting water on my grass, what do you mean? I’ve got to protect my investment here. My lawn must be green.’”

Langford has written about his plight for The Hill Country Alliance, a non-profit that raises awareness towards natural resource and heritage issues in Central Texas. I called Christy Muse, the Executive Director of the Alliance, to learn more about the dynamic between rural landowners and developers when it comes to water use.

[“I]n other areas of the country you can regulate how much new development can happen in rural areas,” Muse said. “You can regulate density, impervious cover, land use. In Texas we choose not to regulate that in rural and unincorporated areas.”

Muse believes that in order to sustain a healthy water supply, more land needs to be kept in a natural state, because land is what captures, stores, and purifies water. There are different ways of accomplishing this: through incentives, such as purchasing development rights, and through regulations. However, many landowners don’t see the long-term payoff because commercial and industrial development can still happen around them, using up their common water supply so they end up selling their land along with the water underneath.

“Landowners’ mantra is to protect private property rights,” Muse said. “This creates an interesting dynamic because in protecting those rights they haven’t really separated out development. So when they’re at the legislature defending private property rights they often end up defending development rights too.”

Many landowners would rather rely on education and awareness than regulation and oversight. Muse says that can only go so far. “Like in society – it’d be nice to rely on education and awareness for any issue, but at some point you have to put laws in place to prevent harm to the community. There’s got to be the carrot and the stick.”

Muse emphasizes that regions can’t accommodate unlimited growth. Already, municipalities in the area are looking for ways of exceeding their watershed capacities by bringing in outside water sources, an expensive and long-term endeavor. Last fall the Hays Caldwell Public Utility Agency, which includes the cities of Kyle, San Marcos and Buda in Hill Country, voted unanimously to transport up to 10,300 acre-feet of water annually from the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer via a 40-mile pipeline. The water will not be needed for ten to 15 years, but the agency has already spent over $7 million on the project in anticipation of future demand.

“People tend to think that our agencies and our government have all these water issues figured out,” Muse said. “To me it’s amazing that more ears aren’t perking up and people aren’t realizing how much water is controlled by a small minority of landowners.”

When I met with Leurig again, this time in a crowded Austin bar during happy hour, I was struck by her positive assessment of Texas’s long-term water situation. “Texas has immense amounts of water as a state, it’s just really poorly allocated,” Leurig said, raising her voice above the din. “People are so fixated on adding more supply because we’re a supply-side state and think of water in the same we way do oil and gas: drill more, produce more. And because of this we neglect solutions we could be implementing on the demand side.”

Leurig is qualified to talk about long-term horizons for water issues not just because of her fascination with springs but also because of her job representing large investors with long-term investment horizons, like pension funds, and helping them understand how trends like climate change and water scarcity will affect the value of their investments. Much of what she does involves helping U.S. water providers transition to a business model in which they can sell less water – counterintuitive to providers, whose business model is to sell more water to make more money.

“What I’m trying to do in Texas is dispel the myth that population increase means that we need more water,” Leurig said, pausing for a sip from her drink. “These huge water projects are bad for ecosystems and too expensive for communities to be building. So I try to help people understand how you really estimate demand and then plan appropriately for supply. At the end of the day, Texas doesn’t have the water crisis Texas thinks it has.”

***

As Texas becomes more like a western state, with fully allocated rivers, increased conflict between water users, and quickly evaporating water surpluses, Leurig believes there will be big changes. The Texas panhandle will no longer be an agricultural society. Natural resources and ecosystems will be lost, threatening deep-seated cultural activities such as hunting and fishing. And the Hill Country could lose many of its springs.

As an example of an instance where policy, education, and conservation overlap, Leurig cites the recent increase of well drilling on private property in West Austin as a response to the newly introduced tiered pricing model aimed at reducing water use. Instead of scaling back, very wealthy customers are drilling wells on their property to water their yards in order to avoid the higher rates of the newly-introduced tiered pricing model aimed at reducing water use. If enough people do this, it could undermine the security of their collective groundwater supply.

In her day job, Leurig strips problems of any emotion or value judgment and communicates in terms of economics, with which she can make a sound argument based on better water management. Her project chronicling Texas’s springs is much more about helping people connect emotionally.

Leurig’s next multi-day springs trip for her blog will be to Val Verde County west of San Antonio along the U.S.–Mexico border. On this trip she’ll meet with stakeholders, many of them landowners, to discuss the future of the region’s groundwater. San Felipe Springs are the fourth largest springs in Texas. Many are concerned that piping the water to San Antonio could compromise the springs themselves, an important recreational feature in the town, as well as the public water supply for nearly 55,000 people.

“When researching this trip, what struck me was the state’s dependence on landowners to manage its water resources,” Leurig said as a young, tattooed waiter brought our food. “When water is treated like private property it becomes a battle between the landed and the un-landed – it’s about Texas’s rural past versus its urban future.”

“As humans we don’t always make rational decisions,” Leurig said, as she took in the busy scene at the bar, one of many such establishments sprouting up in fast-growing Austin. “We make decisions based on joy and love and hope and aspirations, and I think that’s what springs represent – our identity as people in a place.”

Having only been in Texas a few years, spending time with Leurig greatly enhanced my appreciation for springs all across the state and their integral link to life – to lives both deep into the past and those of coming generations. Several weeks after my tour of Hill Country springs, I went hiking along the Pedernales River just outside of Austin. Not only did I tune into the sound of the flowing river, but I felt the water beneath my feet, far underground, supporting everything above it – plants, animals, farmers and urbanites, all of us needing it to sustain our present and recharge our future.

As Texas heads into another year of severe drought, in which farmers and ranchers fret over aquifer levels, developers fight for water rights, and politicians show unusual willingness to work together to secure a water-bearing future, identity and connection to place is taking on a bigger role. In Austin an art installation called “Thirst” was recently revealed in which a dead cedar elm, painted a ghostly white, hovers on a platform above Lady Bird Lake in the middle of downtown. Passersby on the footbridge stop and take note, the water beneath their feet, as they consider one tree amongst millions that lost its life to drought in the last few years.

14,000-prayer flags with images of the tree drape from a wire along the trail around the lake. Water is absent from the flags themselves, and that absence is what evokes its necessity. The flags blow in the breeze, catching the in the air that we – humans, trees, life – need to survive. Nearby Lady Bird Lake is damned at a constant level, giving the impression of water security, while above the Highland Lakes are at nearly their lowest levels ever and below farmers, flora, and fauna anxiously await their allotment. It often gets taken for granted, but water can really be a drain when it wants to be.