SAGE Magazine is thrilled to award Sarah Maslin’s “A Tale of Two Trails” first prize in our 2013 Environmental Writing Contest.

Right before the Appalachian Trail crosses the Massachusetts-Connecticut border, it makes a sharp left turn. Then it climbs Bear Mountain, the highest peak in Connecticut, and zigzags in a southwest descent until it hits the town of Salisbury.

I know this because I’m looking down at it. Actually, I’m looking down at Google Maps’ representation of it — on an iPhone, on the side of the trail, where I’m sitting atop Bear Mountain.

The iPhone belongs to Olivia Gomes, an athletic 37-year-old with a big backpack, hiking poles, pigtails, sunglasses and a bandana. She’s walking the entire 2,000-some miles of the trail with her boyfriend, Nicholas Olsen, 32 — dressed the same, no pigtails, a beard — and their dog, Bailey. Gomes and Olsen (trail names: “Hermit” and “Grizz”) are part of a new generation of Appalachian Trail thru-hikers for whom spending six months on the trail no longer means shedding all the comforts of modern civilization.

Last summer, the Appalachian Trail experienced a spike in the number of hikers heading north from Georgia — 2,500 as of November 2012, compared to 1,700 in 2011. The northbound hiker count in 2012 was 65% higher than it was five years ago, causing considerable concern for the trail’s fate if the trend should continue. But statistics on thru-hikers vary unpredictably from year to year, and even back in the 1980s some complained that the trail was too crowded. Given that the A.T. spans over 2,000 miles along the East Coast, it’s hard to imagine several hundred more people changing the hiking experience.

But what if they have iPods and cell phones? In recent years, technology use on the trail has exploded. By now, nearly every thru-hiker carries a mobile phone, and iPads and Kindles make regular appearances in shelters. Gadgets are used for everything from watching Seinfeld to trading stocks, and their sudden ubiquity is causing some longtime lovers of the Appalachian Trail — a 75-year-old “wilderness footpath” traditionally seen as an escape from modern society — to question the value of today’s hiking experience.

A hiker myself, I’m initially surprised to see iPhones in the woods. I assumed that people thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail to get away from technology and crowds. That’s what appeals to me about hiking, and when I hit the trail, I turn off my phone. I figured today’s A.T. thru-hikers would share this mindset. But maybe I was wrong.

***

Gomes and Olsen mainly use their smart-phone to read its maps and to stay in touch with family (Gomes’ daughter is back home in Key West). They also check weather on it, pay bills, and order hiking gear online, which they pick up a few days later at a post office in town. Sometimes at the top of a mountain they’ll pull the phone out to make calls — it’s the only place with service. Recently, they’ve been using Google Images to identify trailside plants to find out if they’re edible. So far, so good — in the three months they’ve been on the trail, neither hiker has been poisoned.

The phone isn’t the only gadget they brought along for their “Walk in the Woods.” They also have Spot, a fist-sized black and orange tracking device that can alert emergency services with the push of a small red button. It’s linked to Gomes’ blog and to her Facebook page, displaying their location every night, and it automatically sends a text-message to her daughter and mother with their daily GPS coordinates.

It’s a nice day on Bear Mountain — sunny and clear enough to see far off into the distance, where patches of orange and red hint that Connecticut’s leaves are just beginning to change. Looking out over the tree line, I can see the woods and pastures that the Appalachian Trail will weave through for 63 miles before heading into New York.

On Google Maps, the trail is just a squiggly grey line that stretches down the East Coast some 2,000 miles — from Katahdin, Maine to Springer Mountain, Georgia.

***

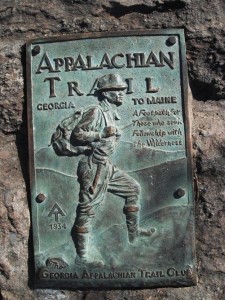

The Appalachian Trail was dreamed up in the 1920s by outdoors enthusiast Benton MacKaye. Mackaye envisioned a single trail running down the whole East Coast, dotted with shelters along the way. In Mackaye’s mind, the trail would serve as an “escape from civilization,” and it was important to him that users “preserve… a certain environment” of solitude and reverence to nature. Without such an environment, Mackaye insisted, the trail’s “whole point is lost.” In order to keep the trail as wild as possible, it was to be built and maintained entirely by volunteers.

The 2,000-plus-mile “wilderness footpath” was completed on August 14, 1937, thanks in large part to the determination of Connecticut judge Arthur Perkins and Washington lawyer Myron H. Avery — along with the labor of 200 or so volunteers, who spent thousands of hours bushwhacking and blazing the trail. In 1937, nobody thought it could be hiked from start to finish.

The 2,000-plus-mile “wilderness footpath” was completed on August 14, 1937, thanks in large part to the determination of Connecticut judge Arthur Perkins and Washington lawyer Myron H. Avery — along with the labor of 200 or so volunteers, who spent thousands of hours bushwhacking and blazing the trail. In 1937, nobody thought it could be hiked from start to finish.

But in 1948, a stubborn army vet named Earl Shaffer walked from the southernmost trailhead in Georgia to the northernmost trailhead in Maine. It took him just 124 days, and it signaled the start of a trend that has grown increasingly popular ever since. While fewer than fifty thru-hikes were recorded before 1970, more than seven hundred finished the trek in 2011 alone. Four times as many tried, but for one reason or another had to drop out along the way.

***

When Jim Liptack hiked the trail in 1980, he didn’t have a cell phone. He relied on letters and the occasional pay phone in town to let his mother know he was okay (he was twenty; she was worried sick). He also didn’t have an iPod — a common accessory on the trail today. This new trend elicits a “What can ya do?” shrug from Liptack, 52.

“They’re missing out,” he says to me as we hack away at overgrown branches that threaten to strangle the narrow trail. As Overseer of Trails for the Connecticut Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) — the volunteer organization responsible for sections of the trail in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania — Liptack takes his job seriously, even though he doesn’t get paid. In the thirty years since he completed his thru-hike, most of his weekends from March to November have been spent moving rocks to build staircases, shoveling dirt to create water-bars, clearing brush, and directing work crews.

Our goal today, he tells me after I’ve been outfitted with a pair of heavy metal loppers, is to clean up this section of the A.T. (“Ten Mile Trail”) so that a hiker could walk on it tightrope style, both arms extended, without smacking into anything. Or, as Benton Mackaye once said, our goal is to create a strip of trail with just enough “space for a fat man to get through.”

It’s a warm Wednesday in late September, and in the afternoon we run into a southbound couple at Ten Mile Shelter. Ear-buds dangle from the guy’s shoulder straps — he tells us he’s been listening to an audio book: “The Maze Runner.” Hiking ten to twelve hours a day can be mentally draining, he explains, and the iPod keeps him from getting bored.

When we leave the shelter, Liptack admits that he would never bring an iPod into the woods.

“I like to listen to the sounds of the wind, the birds, the trees,” he says, snatching a dead branch from above his head and hurling it off to the side of the trail.

Liptack did a lot of listening that dry summer in 1980. He recalls hearing a faint, constant, rain-like noise, even on sunny days. He eventually discovered that it was the sound of gypsy moth caterpillars munching on leaves.

“That plugged-in hiker wouldn’t have heard any of it,” Liptack says. In fact, in Liptack’s day, a hiker with an iPod probably would have been “shunned,” like the two or three brave souls on the trail in 1980 who dared to carry radios.

Liptack, seeking “total detachment from the world,” often hiked alone. The solitude, the wilderness, and the hiking gave him a profound sense of accomplishment, and an appreciation for the outdoors that has stuck with him for more than thirty years.

“The Appalachian Trail is a big part of my life,” he says, and judging by his AMC hat, his “Trail Volunteer” shirt, and the six or seven colorful patches on his green canvas backpack, each proudly displaying a wilderness achievement, I don’t doubt him one bit.

***

Yeah, you’ll meet some idiots pretending to be Thoreau,” says a 48-year-old Californian who calls himself “Pesky,” “but most of us are constantly going in and out of town.”

It’s early September, and I’ve just driven from New Haven to Salisbury — a sleepy Connecticut town nestled between Route 41 and Route 44, less than a mile from the Appalachian Trail. My plan was to head into the woods, find some thru-hikers, and get a sense of the trail scene as it stands in 2012. But I quickly discovered that there were hikers right here in town.

I met Pesky outside the library. He plunked his huge backpack down on a bench, pulled out an iPad, held it at arm’s length, and filmed himself chugging a bottle of Coke.

“It’s kind of a tradition,” he said. “I’m the guy who whips out a coke at the top of the mountain and drinks it in front of everyone.” Then he stuck out his hand and introduced himself.

Now he’s educating me about this year’s thru-hikers. We’re seated at a table outside a café — me, Pesky, his buddy “Sticks,” and my friend Ira, who has come along for company on my venture into the woods.

I had thought anyone willing to spend six months on the trail would resemble some kind of mountain man, so I was surprised when the first two thru-hikers I met looked more like grungy actors from an Apple commercial. But according to Pesky (or, as he’s known in the real world, John Kay) and Sticks (Matthew Cook, a lanky 25-year-old from Australia), the Appalachian Trail today is not a wilderness experience.

They tell me about fancy trailside hostels that charge $50-$100 a night, “hiker clans” called “Riff Raff” and “Wolf Pack” that shuttle booze to shelters in the South, and big events like “Trail Days in Damascus,” a three-day music, food, and crafts festival that draws thousands of hikers to a section of the trail that runs right through downtown Damascus, Va.

But if there’s one thing that has changed the thru-hiking experience most “dramatically,” says Pesky, it’s cell phones. Cell phones make getting to town much easier, he says, and in bad weather many hikers opt to call hostels or motels instead of toughing it out and camping. Cell phones also allow hikers to stay in contact with each other on the trail, which leads to rumors and drama. Pesky remembers one instance in which a group of hiker friends got into a fight. The news spread via text messaging, and by the end of the day, thru-hikers twenty miles up the trail knew that “Team Aqua [had] split up!”

Sticks says it struck him as odd at first, and “a little annoying,” to hear fellow hikers at the top of a mountain talking on their cell phones.

“What the fuck did you come out here for?” he remembers thinking. But he’s gotten used to technology on the trail after being around Pesky, who carries two iPods, a solar charger, and an iPad. Pesky uses the iPad to watch “The Office” and “New Girl” in his sleeping bag, and also to trade stocks (the money he makes from US steel and Micron funds the remainder of his thru-hike). He doesn’t carry a cell phone, however, and jokes that he and Sticks must be the only two hikers without one. (I met twelve thru-hikers that weekend, and it sure seemed like he was right.)

As I listen to Pesky and Sticks talk about technology, drunk hikers, Lord of the Rings movie nights, and internet-based trail rumors, the Appalachian Trail begins to sound more like a college campus than a “wilderness footpath.” Later that week, after watching several Youtube videos of intoxicated thru-hikers, I find a thread on an A.T. forum, Whiteblaze.net, asking if the trail is really just “One big frat party?” It’s not the first time I’ve heard that phrase.

“It’s nature’s frat party,” Pesky says with a smirk, sensing my surprise when he mentions rampant drug and alcohol use on the trail in the South.

But wait a minute — what about Jim Liptack, what about his nature and his solitude? What about Benton Mackaye’s “escape from civilization”? What about the National Geographic article from 1987, in which Noel Grove wrote that Appalachian Trail “hikers revert to lives of simplicity, denying themselves modern comfort, seeking purification in an uncorrupted world”? What about my own stressed-out-college-student fantasies of dropping everything to hike the A.T., my dreams of escaping the deadlines and the emails, of spending days (weeks? months?) without seeing another human face, of learning to fend for myself in the woods and feeling eternal oneness with the spirit of the trees?

I ask Pesky and Sticks.

“Now that’s just hokey,” Pesky laughs.

“It’s a misconception,” says Sticks. “You need to blaze your own trail somewhere else if you want that.” While Sticks has walked hundreds of miles in remote Australia, navigating with only map and compass, he says that the Appalachian Trail is a far different experience — one that’s more crowded and less wild. “The more you walk, the less you care about nature,” he says. He recently bought a Kindle.

When I scribble this down, a slow grin comes across Pesky’s face.

“On the Appalachian Trail,” he says, “we’re mollycoddled the whole way.”

***

Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia is known as the “psychological halfway point of the trail,” though the actual halfway marker is about 75 miles north. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy shares a building downtown with the Harper’s Ferry Visitor Center. It’s a two-story building, built of native stone, where staff have been photographing thru-hikers since 1979. The Conservancy began in the early days of the trail as a yearly conference devoted to preservation and management, but nowadays it also keeps records on hikers and publishes a bimonthly magazine called “Journeys” about all things A.T.

Laurie Potteiger has worked at the Conservancy headquarters for 25 years, starting the spring after she became a “2,000-miler.” Potteiger attributes this year’s increased hiker population to a mild winter, a poor economy, and a National Geographic film about the A.T. that recently became available on Netflix, raising interest in the trail. In the past, she says, books like Ed Garvey’s 1971 “Appalachian Hiker” and Bill Bryson’s “A Walk in the Woods” had similar effects. But the jump this summer was unexpected.

“We really felt it here,” she says. “We were printing [halfway-point picture] postcards all day long.” The ATC started selling personalized postcards to hikers a few years ago.

The effects of increased hiker traffic were felt on the trail, too. A conference call Potteiger conducted with trail managers fielded reports of “considerably more trash,” and more graffiti in shelters that “could be tracked to thru-hikers.” AMC ridge-runners in Connecticut said that they collected more than 700 gallons of garbage from the trail.

In previous years, graffiti and trash were usually blamed on people who used the shelters for the day or the weekend. Thru-hikers, familiar with outdoor ethics, tended to be more respectful. Potteiger wonders if this year’s 2,500 hikers included a greater percentage with “no outdoors experience whatsoever.”

To respond to the trash issues, the Conservancy launched a new “Leave No Trace” initiative, replacing old signs with new ones tailored to different kinds of settings. But Potteiger readily acknowledges that more efforts may be necessary to manage the crowds, especially if hiker counts continue to rise.

“It’s definitely something we’ll be talking about over the winter,” she says.

The new strategy for addressing crowds seems to be to build more campsites, Potteiger tells me. While shelters are expensive and require extensive planning, campsites are much easier to construct. They are also closer to the “primitive experience that the trail is supposed to provide,” she says, explaining that “one of the original purposes of the trail was to provide solitude and contemplation.”

“But how realistic is that kind of experience these days?” I ask her, mentioning all the cell phones I saw on the trail and the stories I heard about partying. Potteiger concedes that there’s been an apparent “cultural shift” in recent years, and she tells me about a picture that alarmed her on Facebook. It depicted a party at a campsite on the trail, with an illegal fire, beer cans, and more than 29 thru-hikers.

“We’re seeing visual evidence like that more and more,” she says.

As for cell phones, Potteiger remembers the first time the staff at Harper’s Ferry heard reports of hikers text-messaging between shelters.

“It blew our minds,” she says. While a survey conducted from 2003-2004 found that less than 15% of hikers carried cell phones, these days Potteiger guesses that only 5 or 10 percent do not have them. Increasing reports of technology on the trail led the Conservancy to create a committee to examine the trend.

Potteiger makes no effort to deny that the Appalachian Trail is changing. However, she is wary of what she calls a “doomsday mindset,” which she says is old news in A.T. history. In the 1980s, she heard similar complaints: the trail was getting too crowded, there was too much partying, the prevalence of “yellow blazing” (using cars to get ahead) meant that people weren’t taking hiking seriously enough.

Twenty years later, the rhetoric is still the same. But now, instead of cars, it’s cell-phones.

“You’d think the trail would be ruined by now,” Potteiger says. According to her, it’s not.

***

I hang up the phone marveling at Potteiger’s laissez-faire attitude towards the trail. How is it, I wonder, that a thru-hiker from 1987 can acknowledge the A.T.’s “original purpose” as a place of wilderness and solitude, admit (without a hint of anger or nostalgia) that today’s gadget-heavy trail has strayed from this purpose, and nevertheless insist that the Appalachian Trail will survive for decades to come?

After hearing Potteiger caution against overly pessimistic views of the trail, I begin to regret turning my nose up at tech-savvy outdoorsmen like Pesky. I suddenly feel foolish for fearing that the A.T. will no longer exist by the time I get around to hiking it. After all, who am I to judge? I’ve walked less than 50 miles of the trail. I sense there’s something I don’t yet understand about the A.T., something that might explain Potteiger’s lack of concern.

If the 75-year-old footpath is no longer a place of wilderness and solitude, I wonder, what is the value of today’s Appalachian Trail?

***

After leaving Pesky and Sticks at the café, where they are using their tablets to friend each other on Facebook, Ira and I drive out to “the boondocks” — the Housatonic State Forest, fifteen minutes outside of Salisbury — for dinner at the Bearded Woods Hiker Hostel.

I’d seen rumors on Whiteblaze.net that this new hostel in Connecticut was taking in thru-hikers, and, curious about the alternative to camping, I decide to check it out. As towns near the Appalachian Trail have started catering to rising hiker populations, the number of hostels along the trail has grown. No doubt their business is aided by the internet and cell phones — Bearded Woods is more than ten miles from the trail, but it offers trailside pick-up if you call ahead.

When I call the number listed online, a gruff voice answers: “Yello, this is Hudson.” I explain that I’m interested in seeing the hostel, and he insists that I come for dinner that night. If I want to learn about the hostel, I have to meet “Big Lu.”

“Big Lu” turns out to be LuciAnn Young, 46 years old and 4’10” tall, a business analyst from New York. ‘Hudson,’ 41, is her husband Patrick Young, a furniture maker from the Hudson Valley. He hiked the A.T. in 2008 and only responds to his trail name — if you forget and call him by his real name, he’ll reply, “Who’s Pat?”

Two hikers from Virginia, “Rhyno” and “Adventure Girl,” are seated at the table when we arrive. Rhyno stayed at Bearded Woods for several nights on his hike up to Maine, and on his drive back down with his girlfriend, Adventure Girl, he decided to stop by the hostel to introduce her to Hudson and Big Lu.

We eat on their candlelit screen porch, surrounded by the sound of crickets. As Big Lu hustles in and out of the kitchen, returning each time with a heaping plate of food, I realize what Pesky meant when he said that today’s hikers are “mollycoddled.” For $50 a night, including two home-cooked meals, laundry service, internet, and transportation, Bearded Woods to a hiker would resemble a five-star hotel. If this is roughin’ it, I think to myself, Paris Hilton could hike the Appalachian Trail.

I notice Hudson’s framed picture of Mt. Katahdin and the collection of animal skins he found in the woods: mink, bobcat, weasel, lynx, beaver, raccoon. I gather that he sees himself as a true outdoorsman, so I’m curious to hear his thoughts on today’s Appalachian Trail. Do hostels prevent people from camping and discovering nature? Are iPods and cell phones ruining the thru-hiking experience?

Hudson shakes his head.

“It’s not about the hike,” he says. “It’s about the people.” Big Lu, Rhyno, and Adventure Girl nod. Hudson’s fellow hikers, the owners of hostels he stayed at, and the folks who gave him a ride or a bite to eat in town — they are what he remembers about his thru-hike, not the trees or the flowers. The value of the Appalachian Trail today is largely social, he tells me, and cell phones and hostels can’t change that. In many ways, technology facilitates friendships — Rhyno and Adventure Girl wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for cell phones. If I hadn’t stumbled upon Bearded Woods on the web, Ira and I wouldn’t either.

Hudson affectionately calls the trail “the world’s longest small town” because of the community that surrounds it. In fact, the Appalachian Trail has long been known as a “people’s trail,” due to the wide network of supporters it attracts and the lifelong bonds it instills between hikers. In 1987, Noel Grove wrote about “trail magic,” a phrase used by thru-hikers to describe little acts of kindness performed by total strangers. It’s still a common saying today, and Hudson credits it for inspiring him to open a hiker hostel.

The A.T. community made an impact on Hudson’s life and he wanted to be a part of it. Upon reaching Katahdin in 2008, he began to look for property in Connecticut near the Appalachian Trail. After transforming the damp basement of an abandoned house into a cozy den of bunkbeds that sleeps ten to twelve, Hudson and Big Lu opened Bearded Woods this past May. Hudson hiked to all the shelters in Connecticut to drop off flyers with information about the hostel. When he discovered a week later that they had been removed, he returned to the shelters to leave more.

This time, he got a phone call from an AMC representative.

“You gotta get rid of your flyers,” the representative said. “No advertising in shelters.”

Hudson was offended — he saw his flyers as a service to hikers, not as “advertisements.” Besides, he says, hikers leave things for each other in the shelters all the time: train schedules, restaurant menus, maps, Bibles.

“How come the AMC doesn’t call up Metro North and tell them to remove their train schedules?” he says. Nevertheless, he hiked back in and removed the flyers. Word of the hostel spread on the trail and on the internet, and by the middle of the summer, when Rhyno visited, Bearded Woods had guests every night.

***

It’s funny that one of the AMC committee members who got Hudson so worked up happens to be the only man in the state who can match his obsession with the Appalachian Trail.

Jim Liptack chuckles when I ask him if the Connecticut AMC has ever had any problems with people posting things in shelters.

“Yeah, funny you ask,” he says, “the Bearded Woods guy left a whole bunch of flyers in all the shelters earlier this summer.”

“Oh, really?” I ask.

“We had to ask him to take them down,” Liptack continues. “There’s a law against advertisements on National Park land.” Roughly 60% of the Appalachian Trail sits on land that belongs to either the Parks Service or the Forest Service, he explains. If the AMC allowed hostel owners to put up flyers, sooner or later McDonald’s would be vying for ad space.

I ask Liptack if he’s bothered by commercialized hostels like Bearded Woods, or by stories of the partying that takes place on the trail in the South. Surely the experience has changed since he thru-hiked in 1980. Have these changes been for the worse?

“It’s more socially oriented,” he says, confirming what I heard from Hudson. But that’s a natural consequence of the growing popularity of the trail, he says, which is a good thing. It means more people are getting out there.

I remind him of his own quiet thru-hike, and his reflections on the importance of wilderness and solitude. After all, that was the trail’s founding purpose, right? Hasn’t today’s trail, with its cell phones and crowds, lost some of its original value?

Despite my prodding, Liptack is ambivalent. Like fellow old-timer Laurie Potteiger, he remains optimistic about today’s A.T., and while he acknowledges a shift in trail culture, he refuses to mourn the loss of yesterday’s technology-free trail. In an attempt to explain his attitude — or perhaps to put an end to my questions — Liptack tells me about a philosophy that has characterized the trail from the start.

The philosophy is best described by the trail saying “Hike Your Own Hike.” It’s a handy tool for ending arguments between opinionated outdoorsmen — on the trail, in shelters, and on online forums like Whiteblaze.net, where it’s abbreviated as “HYOH.”

According to Liptack, the freedom to hike one’s own hike is an important value of the trail. If your ideal hike is a gadget-free quest for nature and solitude, so be it. But if you want to walk with twenty-five friends and listen to Madonna, that’s okay, too.

Besides, Liptack says, “eventually, the batteries run out.” At that point, hikers have no choice but to listen to the wind and the trees.

His point is that even with technology’s distractions — and even if the Appalachian Trail is no longer “wilderness” — thru-hikers experience a whole lot more “nature” than your average American does. I joke that they might be getting more human interaction, too.

“You may be right,” Liptack says.

In fact, I realize, maybe that’s part of the reason why so many people are flocking to the Appalachian Trail. The largest demographic of thru-hikers is typically college students and twenty-somethings, a group that nowadays you’d be more likely to find on a computer than on a trail. Nevertheless, the A.T. saw more hikers in the summer of 2012 than ever before. For a generation that’s criticized for being too self-centered and consumed by technology, perhaps today’s Appalachian Trail still constitutes a kind of “back to basics” — not necessarily back to nature, but back to people.

These days, the social aspect of the trail is what lures people, more so than the “solitude.” What matters for today’s hikers is not the chance to get away from society, but the opportunity to enter a new society — the Appalachian Trail community, where people call each other special names, share in the mutual suffering of hiking hundreds of miles, and where, as one 22-year-old thru-hiker called “Smoked Nutz” told me, “you can be your best self.”

We live in a world full of smart phones and iPads, so of course these gadgets have found their way onto the Appalachian Trail. But an A.T. that prioritizes community can’t be ruined by technology or crowds. Such a trail may even have a place for the occasional frat party.

Hudson’s “small town” is getting bigger, and the Appalachian Trail community is becoming more visible, with thru-hiking blogs and websites like Whiteblaze.net, where every aspect of the trail is dissected and debated. Whiteblaze, which calls itself “A Community of Appalachian Trail Enthusiasts,” has over 40,000 members and 70,000 threads.

The most frequently visited pages on Whiteblaze are the “Thru-Hiker Registries”: long lists of past, present and future hikers, displaying their trail names, their start dates, and a few phrases expressing their excitement to get on the trail (“The bug started a couple years ago and has taken over my life!!! I am so excited to get out there and do this!!!!”). Last September, though they still had months to wait before the snow melted in Georgia, “Class of 2013” hopefuls were already discussing their plans.

***

With this community in mind, I buy a pumpkin pie before heading up Bear Mountain. If we encounter an aggressive hiking clan, I tell Ira, I’ll befriend them with a slice. Then they’ll break out the beer and the projector screen, and we’ll watch Seinfeld atop the mountain. I’ll offer to recycle their beer cans. I won’t turn up my nose.

But when we reach the top, it’s quiet. I stake out a sunny rock beside the trail to wait for the crowd. Some picnickers pass by with their dogs, and some day-hikers in fanny-packs cheer at the summit.

It’s late in the hiking season, and I’ve been told we were lucky to run into thru-hikers in town. Most of the northbounders are further north by now, and the southbounders are further south. Even in the middle of July, I realize, it would be rare to see a crowd in Connecticut. The big wave of hiker traffic starts in Georgia, thinning out over 2,000 miles of trail.

A couple hours pass. I’m beginning to think we might not see any thru-hikers at all, when a loud bark echoes from the other side of the mountain. A few minutes later, a black and white dog rounds the bend, followed by two thru-hikers who introduce themselves as “Hermit” and “Grizz.”

Hermit and Grizz (real names: Olivia Gomes and Nicholas Olsen, the tech-savvy hikers from Key West I mentioned earlier) eagerly accept my offer of pumpkin pie. By the time they’ve scarfed down two slices apiece, we’re deep into a discussion about the changing culture of the Appalachian Trail.

Despite their matching bandanas and their mutual reliance on Gomes’ iPhone, the two hikers say they’re “like Yin and Yang” when it comes to how they perceive the trail.

For Olsen, its value lies largely in the A.T. community. A self-proclaimed “social butterfly,” he had a blast partying until dawn at “Trail Days in Damascus,” where his new thru-hiker friends christened him “Grizz” because of his untamed beard and wild antics. Gomes, on the other hand, chose the A.T. to get away from Florida’s crowds, and her shyness and “No Shelters policy” quickly earned her the trail name “Hermit.”

The couple has somehow made thru-hiking together work, with a little bickering, a lot of give and take, and frequent invocations of “Hike Your Own Hike!”

Nevertheless, even Olsen, the Social Butterfly, occasionally gets sick of crowds, and he says he prefers catching dinner with his collapsible fishing rod to eating at a restaurant in town. And Gomes, the Hermit, despite “wish[ing] sometimes that the trail were more wild,” realizes she’s no Thoreau. To prove it, she leans over to show me her iPhone map of the trail.

Olsen raises his eyebrows. “I’m surprised she’s talking so much to you,” he says.

“Must be the pie,” I say.

Ira and I end up camping that night at the same site as Gomes and Olsen, a couple miles farther south on the trail towards Salisbury. It gets dark quickly in the woods, and after setting up our tent and eating some Clif Bars on a nearby boulder, we climb into our sleeping bags and begin to doze off, listening to the wind in the trees.

Before falling asleep, I pull my iPhone out from under my head. I forgot to look something up on the internet earlier, and I have to set my alarm. I find out on Google that the sun will rise at 6:35 am tomorrow. I set my alarm for 6:15. It’s supposed to be a beautiful morning, and I don’t want to miss it.